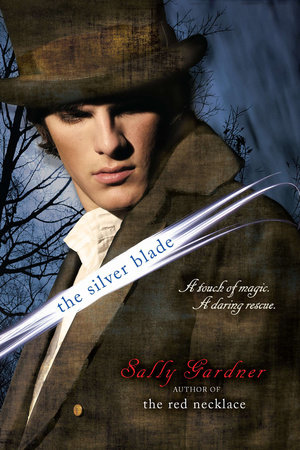

The Red Necklace

Paperback

$16.00

- Pages: 400 Pages

- Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

- Imprint: Speak

- ISBN: 9780142414880

An Excerpt From

The Red Necklace

Here, then, is where our story starts, in a run-down theater on the rue du Temple, with a boy called Yann Margoza, who was born with a gift for knowing what people were thinking, and an uncanny ability to throw his voice.

Yann had a sharp, intelligent face, olive skin, a mop of jet-black hair, and eyes dark as midnight, with two stars shining in them. He was a solitary boy who enjoyed nothing better than being left alone to explore whatever city or town he was in, until it felt to him like a second skin.

For the past few months the theater had been home to Yann and his friend and mentor, the dwarf Têtu.

Têtu acted as assistant to his old friend Topolain the magician, and together they traveled all over France, performing. Without ever appearing on stage, he could move objects at will like a sorcerer, while Topolain fronted the show and did tricks of his own. Yann was fourteen now, and still didn’t understand how Têtu did it, even though he had helped behind the scenes since he was small.

Têtu’s age was anyone’s guess and, as he would say, no one’s business. He compensated for his small size and his strange high-pitched voice with a fierce intelligence. Nothing missed his canny eye, nobody made a fool of him. He could speak many languages, but would not say where he came from.

It had been Têtu’s idea to invest their savings in the making of the wooden Pierrot.

The clown was built to designs carefully worked out by Têtu; it had a white-painted face and glass eyes, and was dressed in a baggy blue top and trousers.

Topolain had not been sure that he wanted to perform with a doll.

“A doll!” exclaimed Têtu, throwing his arms up in disgust. “This is no doll! This is an automaton! It will make our fortunes. I tell you, no one will be able to fathom its secret, and you, my dear friend, will never tell.”

Topolain rose to the challenge. The result had been a sensation. Monsieur Aulard, manager of the Theater du Temple, had taken them on and for the past four months they had played to full houses. Monsieur Aulard couldn’t remember a show being sold out like this before. In these dark times, it struck him as nothing short of a miracle.

The Pierrot had caught people’s imaginations. There were many different opinions going around the neighborhood cafés of the Marais as to what strange alchemy had created it. Some thought that it was controlled by magic. More practical minds wondered if it was clockwork, or if there was someone hidden inside. This theory was soon dismissed, as every night Topolain would invite a member of the audience up on stage to look for himself. All who saw it were agreed that it was made from solid wood. Even if it had been hollow, there was no space inside for anyone to hide.

Yet not only could the Pierrot walk and talk, it could also, as Topolain told the astonished audience every night, see into the heart of every man and woman there, and know their darkest secrets. It understood their plight even better than the King of France.

For the grand finale, Topolain would perform the trick he was best known for—the magic bullet. He would ask a member of the audience to come up on stage and fire a pistol at him. To much rolling of drums, he would catch the bullet in his hand, proclaiming that he had drunk from the cup of everlasting life. After seeing what he could do with the automaton, the audience did not doubt him. Maybe such a great magician as this could indeed trick the Grim Reaper.

Every evening after the final curtain had fallen and the applause had died away, Yann would wait in the wings until the theater was empty. His job then was to remove the small table on which had been placed the pistol and the bullet.

Tonight the stage felt bitterly cold. Yann heard a noise as a blast of wind howled its mournful way into the stalls, and peered out into the darkened auditorium. It was eerily deserted, yet he could have sworn he heard someone whispering in the shadows.

“Hello?” he called out.

“You all right?” asked Didier the caretaker, walking onto the stage. He was a giant of a man with a deep, gravelly voice and a vacant moonlike face. He had worked so long at the theater that he had become part of the building.

“I thought I heard someone in the stalls,” said Yann.

Didier stood by the edge of the proscenium arch and glared menacingly into the gloom. He reminded Yann of a statue that had come to life and wasn’t on quite the same scale as the rest of humanity.

“There’s no one there. More than likely it’s a rat. Don’t worry, I’ll get the blighter.”

He disappeared into the wings, humming as he went, leaving Yann alone. Yann felt strangely uneasy. The sooner he was gone from here the better, he thought to himself.

There! The whispering was louder this time. “Who’s there?” shouted Yann. “Show yourself.”

Then he heard a woman’s soft voice, whispering to him in Romany, the language he and Têtu spoke privately together. He nearly jumped out of his skin, for it felt as if she were standing right next to him. He could see no one, yet he could almost feel her breath like a gentle breeze upon his neck.

She was saying, “The devil’s own is on your trail. Run like the wind.”

Topolain’s dressing room was at the end of the corridor on the first floor. They had been moved down to what Monsieur Aulard grandly called a dressing room for superior actors. It was as shabby as all the other dressing rooms, but it was a little larger and had the decided privilege of having a fireplace. The log basket was all but empty and the fire near defeated by the cold. The room was lit with tallow candles that let drifts of black smoke rise from the wick, turning the ceiling dark brown in color.

Topolain was sitting looking at his painted face in a mirror. He was a stout man with doughy features.

“How did you know the shoemaker had a snuffbox in his pocket, Yann?” he asked.

Yann shrugged. “I could hear his thoughts loud and clear,” he said.

Têtu, who was kneeling on the floor carefully packing away the wooden Pierrot, listened and smiled, knowing that Yann’s abilities were still unpredictable. Sometimes, without being aware of it, he could read people’s minds; sometimes he could even see into the future.

Yann went over to where Têtu was kneeling.

“I need to talk to you.”

Topolain put his head to one side and listened. Someone was coming up the stairs. “Shhh.”

A pair of heavy boots could be heard on the bare wooden boards, coming toward the dressing room. There was a rap at the door. Topolain jumped up in surprise, spilling his wine onto the calico cloth on the dressing table so that it turned dark red.

A huge man stood imposingly in the doorway, his smart black tailored coat emphasizing his bulk and standing out against the shabbiness of his surroundings. Yet it was his face, not his garments, that caught Yann’s attention. It was covered in scars like the map of a city you would never wish to visit. His left eye was the color of rancid milk. The pupil, dead and black, could be seen beneath its curdled surface. His other eye was bloodshot. He was a terrifying apparition.

The man handed Topolain a card. The magician took it, careful to wipe the sweat from his hands before he did so. As he read the name Count Kalliovski, he felt a quiver of excitement. He knew that Count Kalliovski was one of the wealthiest men in Paris, and that he was famed for having the finest collection of automata in Europe.

“This is an honor indeed,” said Topolain.

“I am steward to Count Kalliovski. I am known as Milkeye,” said the man. Milkeye held out a leather purse before him as one might hold a bone out to a dog.

“My master wants you to entertain his friends tonight at the château of the Marquis de Villeduval. If Count Kalliovski is pleased with your performance”—here he jangled the purse—“this will be your reward. The carriage is waiting. We would ask for haste.”

Yann knew exactly what Topolain was going to say next.

“I shall be delighted. I shall be with you just as fast as I can get myself and my assistants together.”

“Haste,” Milkeye repeated sharply. “I don’t want our horses freezing to death out there. They are valuable.”

The door closed behind him with a thud, so that the thin walls shook.

As soon as they were alone, Topolain lifted Têtu off his feet and danced him around the room.

“This is what we have been dreaming of! With this invitation the doors of grand society will be open to us. We will each have a new wig, the finest silk waistcoats from Lyon, and rings the size of gulls’ eggs!”

He looked at his reflection in the mirror, added a touch of rouge to his cheeks, and picked up his hat and the box that contained the pistol.

“Are we ready to amaze, astound, and bewilder?”

“Wait, wait!” pleaded Yann. He pulled Têtu aside and said quietly, “When I went to clear up this evening I heard a voice speaking Romany, saying, ‘The devil’s own is on your trail. Run like the wind.’”

“What are you whispering about?” asked Topolain. “Come on, we’ll be late.”

Yann said desperately, “Please, let’s not go. I have a bad feeling.”

“Not so fast, Topolain,” said Têtu. “The boy may be right.”

“Come on, the two of you!” said Topolain. “This is our destiny calling. Greatness lies ahead of us! I’ve waited a lifetime for this. Stop worrying. Tonight we will be princes.”

Yann and Têtu knew that it was useless to say more. They carried the long box with the Pierrot in it down the steep stairs, Yann trying to chase away the image of a coffin from his mind.

At the bottom, fixed to the wall, was what looked like a sentry box. In it sat old Madame Manou, whose task it was to guard the stage door.

“Well,” she said, leaning out and seeing that they had the Pierrot with them, “so you’re going off in that grand carriage, are you? I suppose it belongs to some fine aristocrat who has more money than sense. Dragging you off on a night like this when all good men should be making for their beds!”

“Tell Monsieur Aulard where we’re going,” said Têtu, and he handed her the card that Milkeye had given Topolain.

All Topolain was thinking was that maybe the king and queen would be there. The thought was like a fur coat against the cold, which wrapped itself around him as he walked out into the bitter night, Yann’s and Têtu’s anxieties forgotten.

The carriage, lacquered beetle-black, with six fine white horses, stood waiting, shiny bright against the gray of the old snow, which was now being gently covered by a fresh muslin layer of snowflakes. This carriage looked to Yann as if it had been sent from another world.

Each of them was given foot and hand warmers and a fur rug for the journey ahead. Topolain lay back enveloped in the red velvet upholstery, with its perfume of expensive sandalwood.

“This is the life, eh?” he said, smiling at Têtu. He looked up at the ceiling. “Oh to be rich, to have the open sky painted inside your carriage!”

Effortlessly the coach made its way down the rue du Temple and past the Conciergerie, and crossed the Pont Neuf. Yann looked along the frozen river Seine out toward the spires of Notre Dame outlined against a blue-black sky. He loved this city with its tall lopsided houses, stained with the grime of centuries, stitched together by narrow alleyways.

The thoroughfares were not paved: They were nothing more than open sewers clogged with manure, blood, and guts. There was a constant clamor, the clang of the blacksmith’s anvil, the shouts of the street criers, the confusion of beasts as they were led to slaughter. Yet in amongst this rabbit warren of streets stood the great houses, the pearls of Paris, whose pomp and grandeur were a constant reminder of the absolute power, the absolute wealth of the king.

The inhabitants, for the most part, were crammed into small apartments with no sanitation. Here sunlight was always a stranger. Candles were needed to see anything at all. For that the tallow factories belched out their stinking dragon’s breath that hung tonight and every night in a menacing cloud above the smoking chimneys. It was not hard to imagine that the devil himself might take up residence here, or that in this filth of poverty and hunger grew the seeds of revolution.

On they went, out toward St. Germain, along the rue de Sèvres, where the houses began to give way to snowy woods that looked as if they had been covered in a delicate lace.

Topolain had fallen asleep, his mouth open, a dribble of saliva running down his chin. Têtu had his eyes closed as well. Only Yann was wide-awake. The farther away from Paris they went, the more apprehensive he became. Try as he might, he could not shake off a deep sense of foreboding. He wished he had never heard the whispering voice.

“The devil’s own is on your trail.”