Found

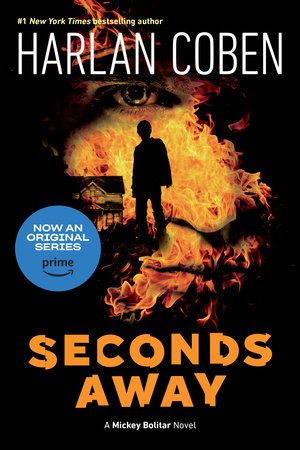

Part of: A Mickey Bolitar Novel

Paperback

$12.99

As mysterious clues continue to surface, Mickey is determined to uncover the truth about his father's death. Was it accidental? Murder? Or is he in fact still alive? With the help of his Uncle Myron and loyal friends, Spoon and Ema, Mickey unravels the mysteries of the Abeona Shelter and the elusive "Butcher of Lodz"—all while trying to navigate the ins and outs of everyday life in high school.

“This third Mickey Bolitar mystery starts at a swift pace and never lets up.”—Booklist

Look for all three books in the series!

“Packed with plot and studded with cliffhangers, Coben's third Mickey Bolitar thriller grabs readers in the opening chapter and never lets go.”—Kirkus Reviews

“This third Mickey Bolitar mystery starts at a swift pace and never lets up.”—Booklist Online

- Pages: 336 Pages

- Series: A Mickey Bolitar Novel

- Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

- Imprint: Speak

- ISBN: 9780147515742

An Excerpt From

Found

CHAPTER 1

Eight months ago, I watched my father’s coffin being lowered into the ground. Today I was watching it being dug back up.

My uncle Myron stood next to me. Tears ran down his face. His brother was in that coffin—no, strike that, his brother was supposed to be in that coffin—a brother who supposedly died eight months ago, but a brother Myron hadn’t seen in twenty years.

We were at the B’nai Jeshurun Cemetery in Los Angeles. It was not yet six in the morning, so the sun was just starting to rise. Why were we here so early? Exhuming a body, the authorities had explained to us, upsets people. You need to do it at a time of maximum privacy. That left late at night—uh, no thank you—or very early in the morning.

Uncle Myron sniffled and wiped his eye. He looked as though he wanted to put his arm around me, so I slid a little farther away. I stared down at the dirt. Eight months ago, the world had held such promise. After a lifetime of traveling overseas, my parents decided to settle back in the United States so that I, as a sophomore in high school, would finally have real roots and real friends.

It all changed in an instant. That was something I had learned the hard way. Your world doesn’t come apart slowly. It doesn’t gradually crumble or break into pieces. It can be destroyed in a snap of the fingers.

So what happened?

A car crash.

My father died, my mother fell apart, and in the end, I was made to live in New Jersey with my uncle, Myron Bolitar. Eight months ago, my mother and I came to this very cemetery to bury the man we loved like no other. We said the proper blessings. We watched as the coffin was lowered into the ground. I even threw ceremonial dirt on my father’s grave.

It was the worst moment of my life.

“Stand back, please.”

It was one of graveyard workers. What did they call someone who worked in a graveyard? Groundskeeper seemed too tame. Gravedigger seemed too creepy. They had used a bulldozer to bring up most of the dirt. Now these two guys in overalls—let’s call them groundskeepers—finished with their shovels.

Uncle Myron wiped the tears from his face. “Are you okay, Mickey?”

I nodded. I wasn’t the one crying here. He was.

A man wearing a bow tie and holding a clipboard frowned and took notes. The two groundskeepers stopped digging. They tossed their shovels out the hole. The shovels landed with a clank.

“Done!” one shouted. “Securing it now.”

They started shimmying nylon belts under the casket. This took some doing. I could hear their grunts of exertion. When they finished, they both jumped out of the hole and nodded toward the crane operator. The crane operator nodded back and pulled a lever.

My father’s casket rose out of the earth.

It had not been easy to arrange this exhumation. There are so many rules and regulations and procedures. I don’t really know how Uncle Myron pulled it off. He has a powerful friend, I know, who helped ease the way. I think maybe my best friend Ema’s mother, the Hollywood star Angelica Wyatt, may have used her influence too. The details, I guess, aren’t important. The important thing was, I was about to learn the truth.

You are probably wondering why we are digging up my father’s grave.

That’s easy. I needed to be sure that Dad was in there.

No, I don’t think that there was a clerical error or that he was put in the wrong coffin or buried in the wrong spot. And, no, I don’t think my dad is a vampire or a ghost or anything like that.

I suspect—and, yes, it makes no sense at all—that my father may still be alive.

It particularly makes no sense in my case because I was in that car when it crashed. I saw him die. I saw the paramedic shake his head and wheel my father’s limp body away.

Of course, I had also seen that same paramedic try to kill me a few days ago.

“Steady, steady.”

The crane began to swing toward the left.

It lowered my father’s casket onto the back of a pickup truck. His coffin was a plain pine box. This, I knew, my father would have insisted upon. Nothing fancy. My father wasn’t religious, but he loved tradition.

After the coffin touched down with a quiet thud, the crane operator turned off the engine, jumped out, and hurried toward the man with the bow tie. The operator whispered something in the man’s ear. Bow Tie looked back at him sharply. The crane operator shrugged and walked away.

“What do you think that was about?” I asked.

“I have no idea,” Uncle Myron said.

I swallowed hard as we started toward the back of the pickup truck. Myron and I stepped in unison. That was a little weird. Both of us are tall—six foot four inches. If the name Myron Bolitar rings a bell, that could be because you’re a basketball fan. Before I was born, Myron was an All-American collegiate player at Duke and then was chosen in the first round of the NBA draft by the Boston Celtics. In his very first preseason game—the first time he got to wear his Celtic green uniform—an opposing player named Burt Wesson smashed into Myron, twisting my uncle’s knee and ending his career before it began. As a basketball player myself—one who hopes to surpass his uncle—I often wonder what that must have been like, to have all your hopes and dreams right there, right at your fingertips, wearing that green uniform you always dreamed would be yours and then, poof, it was all gone in a crash.

Then again, as I looked at the casket, I thought that maybe I already knew.

Like I said before, your world can change in an instant.

Uncle Myron and I stopped in front of the coffin and lowered our heads. Myron sneaked a glance at me. He, of course, didn’t believe that my father was still alive. He had agreed to do this because I asked—begged, really—and he was trying to “bond” with me by humoring my request.

The pine casket looked rotted, fragile, as though it might collapse if we just looked at it too hard. The answer was right there, feet in front of me. Either my dad was in that box or he wasn’t. Simple when you put it that way.

I moved a little closer to the casket, hoping to feel something. My father was supposed to be in that box. Shouldn’t I . . . I don’t know . . . feel something if that were the case? Shouldn’t there be a cold hand on my neck or a shiver down my spine?

I felt neither.

So maybe Dad wasn’t in there.

I reached out and rested my hand on the lid of the casket.

“What do you think you’re doing?”

It was Bow Tie. He had introduced himself to us as an environmental health inspector, but I had no idea what that meant.

“I was just . . .”

Bow Tie moved between my father’s casket and me. “I explained to you the protocol, didn’t I?”

“Well, yes, I mean . . .”

“For reasons of both public safety and respect, no casket can be opened on these premises.” He talked as if he were reading an SAT reading comprehension section out loud. “This county transport vehicle will bring your father’s casket to the medical examiner’s office, where it will be opened by a trained professional. That is my job here—to make sure that we have opened the correct grave, to make sure the casket matches the public records on the person being exhumed, to make sure that all proper health measures have been taken, and finally to make sure that the transport goes smoothly and respectfully. So if you don’t mind . . .”

I looked at Myron. He nodded. I slowly lifted my hand off the soggy, dirty pine. I took a step back.

“Thank you,” Bow Tie said.

The crane operator was whispering now with a groundskeeper. The groundskeeper’s face turned white. I didn’t like that. I didn’t like it at all.

“Is something wrong?” I asked Bow Tie.

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, what’s with all the whispering?”

Bow Tie started studying his clipboard as though it held some special answer.

Uncle Myron said, “Well?”

“I have nothing else to report at this time.”

“What does that mean?”

The groundskeeper, his face still white, started securing the casket with nylon belts.

“The casket will be at the medical examiner’s office,” he continued. “That is all I can tell you at this time.”

Bow Tie moved to the cab of the pickup truck and slid into the passenger seat. The driver started up the engine. I hurried toward his window.

“When?” I asked.

“When what?”

“When will the medical examiner open the casket?”

He checked his clipboard again, but it seemed as if it were just for show, as if he already knew the answer.

“Now,” he said.

CHAPTER 2

We were at the medical examiner’s office, waiting for the casket to be opened, when my cell phone rang.

I was all set to ignore the call. The answer to the key question of my life—was my father dead or alive?—was mere moments away.

A phone call could wait, right?

Then again, I was just hanging around. Maybe a phone call would be a welcome distraction. I quickly checked the caller ID and saw it was my best friend Ema. Ema’s real name is Emma, but she dresses all in black and has a bunch of tattoos, so some of the kids, way back when, considered her “emo” and then someone combined “Emma” with “emo” and cleverly (I’m being sarcastic when I say “cleverly”) dubbed her Ema.

Still, the name stuck.

My first thought: Oh no, something bad happened to Spoon!

Uncle Myron leaned over my shoulder and pointed out the caller ID. “Is that Angelica Wyatt’s daughter?”

I frowned. Like this was his business. “Yep.”

“You two have become pretty tight.”

I frowned some more. Like this was his business. “Yep.”

I wasn’t sure what to do here. I could step away from my hovering uncle and answer it. Uncle Myron could be pretty thick, but even he’d get the message. I held up the phone and said to him, “Uh, do you mind?”

“What? Oh, right. Sure. Sorry.”

I hit the answer button and said, “Hey.”

“Hey.”

I mentioned that Ema was my best friend. We have only known each other a few weeks, but they’ve been dangerous and crazy weeks, life-affirming and life-threatening weeks. People could be friends a lifetime and not come close to the bond that had formed between us.

“Any word yet on the, uh . . . ?” Ema didn’t know how to finish that sentence. Neither did I.

“It could come at any time,” I said. “I’m at the medical examiner’s office right now.”

“Oh, sorry. I shouldn’t have disturbed you.”

There was something in her tone that I didn’t like. I felt my heart leap into my throat.

“What’s wrong?” I asked. “Is this about Spoon?”

Spoon was my second-best friend, I guess. Last time I saw him, he was lying in a hospital bed. He had been shot, saving our lives, and it was now possible that he’d never walk again. I blocked that horrible thought nonstop. I also dwelled on it nonstop.

“No,” she said.

“Have you heard anything new?”

“No. His parents aren’t letting me visit either.”

Spoon’s mom and dad had forbidden me from entering his room. They blamed me for what happened. Then again, so did I.

“So what’s wrong?” I asked.

“Look, I shouldn’t have called. It isn’t a big deal. Really.”

Which only made me sure that whatever it was, it was a big deal. Really.

I was about to argue and insist she tell me why she had called, but Bow Tie came back into the room.

“Gotta go,” I said to her. “I’ll call you when I can.”

I hung up. Myron and I stepped toward Bow Tie. He had his head down, taking notes.

“Well?” Myron said.

“We should have the results in a few moments.”

I realized that I had been holding my breath. I let it out now. Then I asked, “What was all that whispering about?”

“Pardon?”

“At the cemetery. With the guys digging and the one operating the bulldozer.”

“Oh,” he said. “That.”

I waited.

Bow Tie cleared his throat. “The groundskeepers”—so, okay, that’s what they were called—“noted that the casket felt a little . . .” He looked up as though searching for the next word.

After three seconds that felt like an hour passed, I said, “Felt a little what?”

And then he said it: “Light.”

Myron said, “As in weight?”

“Well, yes. But they were wrong.”

That didn’t make any sense. “They were wrong about the casket feeling light?”

“Yes.”

“How?”

He lifted his clipboard, as if it could ward off attacks. “That is all I can say until I have the necessary paperwork.”

“What necessary paperwork?”

“I have to go now.”

“But—”

The door opened behind me. A woman in a business suit stepped into the room. We all slowly turned and stared at her.

“The medical examiner is finished.”

“And?”

The woman looked left and then right, as though someone might be eavesdropping. “Please follow me,” she said. “The medical examiner is ready to speak to you.”

CHAPTER 3

“Thank you for your patience. I’m Dr. Botnick.”

I expected the medical examiner to look ghoulish or creepy or something. Think about it. Medical examiners deal with dead people all day. They slice them open and try to figure out what killed them.

But Dr. Botnick was a tiny woman with an inappropriately happy smile and the kind of red hair that borders on orange. Her office had been completely stripped of any sort of personality. There was nothing personal in the entire room—no family photographs, for example, but then again, in a room filled with so much death, did people want to stare at images of her loved ones? Her desk was bare except for a brown leather desk pad with matching letter tray (empty), memo holder, pencil cup (two pens and one pencil), and a letter opener. The walls had diplomas, and nothing else.

She kept smiling at us. I looked at Myron. He looked lost.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I’m not very good with people. Then again, none of my patients complain.” She started laughing. I didn’t join in. Neither did Uncle Myron. She cleared her throat and said, “Get it?”

“Got it,” I said.

“Because my patients, well, they’re dead.”

“Got it,” I said again.

“Inappropriate, right? My bad. Truth? I’m a little nervous. This is an unusual situation.”

I felt my pulse pick up speed.

Dr. Botnick looked over at Myron. “Who are you?”

“Myron Bolitar.”

“So you’d be Brad Bolitar’s brother?”

“Yes.”

Her eyes found mine. “And you must be his son?”

“That’s right,” I said.

She wrote something down on a sheet of paper. “Could you tell me the cause of death?”

“Car accident,” I said.

“I see.” She jotted another note. “Usually when people request we exhume a body, it is because they wish to move burial grounds. That isn’t the case here, is it?”

Myron and I both said no.

“Where is Kitty Hammer Bolitar?” Dr. Botnick asked.

Kitty Hammer Bolitar was my mother.

“She’s not here,” Myron said.

“Well, yes, I can see that. Where is she?”

“She’s indisposed,” Myron said.

Dr. Botnick frowned. “Like in the bathroom?”

“No.”

“Kitty Hammer Bolitar is listed as the wife and thus the next of kin,” Dr. Botnick continued. “Where is she? She should be part of this.”

I finally said, “She’s in a drug rehabilitation center in New Jersey.”

Again she met my eye. I saw kindness there and maybe a little bit of pity. “There was a famous tennis player named Kitty Hammer. I saw her in the US Open when she was only fifteen years old.”

A rock formed in my chest.

“That’s not relevant,” Myron snapped.

Yes, that was my mother. At one point Kitty Hammer Bolitar had a chance of being one of the greatest female tennis players of all time, up there with Billie Jean King and the Williams sisters. Then something happened that eventually ended her career: She got pregnant.

With me.

“You’re right,” Dr. Botnick said. “My apologies.”

“Look,” Uncle Myron said, “is his body in there or not?”

I watched her face for some kind of sign, but there was nothing. Dr. Botnick would have made a great poker player. She turned her attention to me. “Is that why you’re here?”

“Yes,” I said.

“To find out if your father is in the right casket?”

I said yes again.

“Why do you think your father wouldn’t be in there?”

How could I possibly explain it?

Dr. Botnick looked at me as though she really wanted to help. But even in my own head it sounded insane. I couldn’t tell her about the Bat Lady, who may be Lizzy Sobek, the Holocaust hero everyone thought had died in World War II. I couldn’t tell her about the Abeona Shelter, the secret society that rescued children, and how Ema, Spoon, Rachel, and I had risked our lives in its service. I couldn’t tell her about that creepy paramedic with the sandy hair and green eyes, the one who took my father away and then, eight months later, tried to kill me.

Who would believe such crazy talk?

Uncle Myron saw me squirm in my seat. “The reasons are confidential,” he said, trying to come to my rescue. “Would you please just tell us what you found in the casket?”

Dr. Botnick started chewing on the end of her pen. We waited.

Finally, Myron tried again: “Is my brother in the casket, yes or no?”

She put the pen down on her desk and stood.

“Why don’t you come with me and see for yourself?”

CHAPTER 4

We headed down the long corridor.

Dr. Botnick led the way. The corridor seemed to narrow as we walked, as though the tiled walls were closing in on us. I was about to move behind Myron, walking single file, when she stopped in front of a window.

“Wait here, please.” Dr. Botnick poked her head in the door. “Ready?”

From inside, a voice said, “Give me two seconds.”

Dr. Botnick closed the door. The window was thick. Wires crisscrossed inside of it, forming diamonds. There was a shade blocking our view.

“Are you ready?” Dr. Botnick asked.

I was shaking. We were here. This was it. I nodded. Myron said yes.

The shade rose slowly, like a curtain at a show. When it was all the way up—when I could see clearly into the room—it felt as though seashells had been pressed against my ears. For a moment, no one moved. No one spoke. We just stood there.

“What the—?”

The voice belonged to Uncle Myron. There, in front of us, was a gurney. And resting on the gurney was a silver urn.

Dr. Botnick put a hand on my shoulder. “Your father was cremated. His ashes were put in that urn and buried. It isn’t customary, but it’s not all that unusual either.”

I shook my head.

Myron said, “Are you telling us that there were only ashes in that casket?”

“Yes.”

“DNA,” I said.

“Pardon?”

“Can you run a DNA test on the ashes?”

“I don’t understand. Why would I do that?”

“To confirm that they belong to my father.”

“To confirm . . . ?” Dr. Botnick shook her head. “That technology doesn’t exist, I’m sorry.”

I looked at Myron. There were tears in my eyes. “Don’t you see?” I said.

“See what?”

“He’s alive.”

Myron’s face turned white. In the corner of my eye I could see Bow Tie heading down the corridor toward us.

“Mickey . . . ,” Myron began.

“Someone is covering their tracks,” I insisted. “We wouldn’t cremate him.”

“I’m afraid that’s not true.”

It was Bow Tie. He held up a sheet of paper.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“This is an authorization to have the body of Brad Bolitar cremated per the legal requirements for the State of California. It is all on the up-and-up, including the notarized signature of the next of kin.”

Uncle Myron reached out for the sheet, but I grabbed it first. I scanned to the bottom of the page.

It had been signed by my mother.

I could feel Myron reading over my shoulder.

Kitty Hammer Bolitar had signed a lot of autographs during her tennis days. Her signature was fairly unique with the giant K and the curl on the right side of the H. This signature had both.

“It’s a forgery!” I shouted, though it didn’t look like a forgery at all. “This has to be a fake.”

They all stared at me as though an arm had suddenly sprouted out of the middle of my forehead.

“It was notarized,” Bow Tie said. “That means an independent person witnessed and confirmed that your mother signed it.”

I shook my head. “You don’t understand . . .”

Bow Tie took the sheet back from me. “I’m sorry,” he said. “There is nothing more we can do for you.”

CHAPTER 5

Dead end.

We sat in the airport and waited to board our flight home. Uncle Myron frowned at his smartphone, concentrating a little too hard on the screen. “Mickey?”

I looked at him.

“Don’t you think it’s time you told me what’s going on?”

It was. Uncle Myron deserved to know. He had called in favors and put himself on the line. He had, in a sense, earned my trust. But there were other things to consider. First of all, I had been warned more than once by those in Abeona Shelter not to tell Myron. I couldn’t just ignore that advice.

Second—and this was always front and center—I still blamed Myron for what happened to my parents. When my mother got pregnant with me, Uncle Myron reacted badly to the news. He didn’t trust my mother. He and my dad fought over it. My parents ended up running away overseas and then coming back years later and then . . . well, then it led to my dad being “maybe dead” and my mother being locked up in a drug rehabilitation center.

Uncle Myron waited for my answer. I was wondering how to tell him no when I remembered that I still needed to call Ema back. I held up the phone and said, “I have to take this,” even though the phone hadn’t rung.

I moved away from the gate and hit Ema on my speed dial. She answered immediately.

“So?” Ema said.

“So nothing.”

“Huh? I thought they were about to open the casket.”

“They were. I mean, they did.”

I explained about the cremation. She listened, as always, without interrupting. Ema was one of those people who listened with everything they had. She focused on your face. Her eyes didn’t dart to all corners. She didn’t nod at inappropriate times. Even now, even when she was just on the phone with me, I could feel that concentration.

“And you’re sure it’s her signature?”

“It certainly looks like it.”

“But it could be forged,” Ema said.

“Doubtful. I mean, there was a notary who witnessed it or something. But it could be . . .” My words trailed off.

“What?”

“After my father died, well, that was when she fell apart.”

“She started taking drugs?”

“Yes,” I said, remembering it all now. “In fact, Mom was so out of it . . . I don’t know how she could have made a decision like that.”

“So what now?”

“I fly home. I have basketball practice.”

I know what you’re thinking. Who cares about basketball practice at a time like this? Answer: I do. I get that that sounds warped. But even now—or maybe especially now—I needed to be back on the court. I needed basketball to be a priority. It was the place I thrived and escaped, and no matter what, I longed for it.

“Anything new on Spoon’s condition?” I asked.

“No.”

“How about Rachel?”

Silence.

I waited. Asking about Rachel may have been a mistake, I don’t know. Rachel was a part of our group, much as she, being immensely popular and probably the hottest girl in the school, seemed to have nothing in common with us.

“Rachel’s fine,” Ema said, her voice like a door slamming shut. “She’s dealing, I guess.”

I needed to reach out to Rachel when I got back. I had dropped a huge bomb on her—a life-altering bomb—and then I had flown away to Los Angeles. I needed to remedy that.

“So why did you call before?” I asked.

“It can wait till you get home.”

“Talk to me, Ema. I need the distraction.”

She took a deep breath. I could see her now, sitting alone in that huge gated mansion. “Why us?” she asked.

I knew what she meant. Nothing here had been accidental. A secret group called the Abeona Shelter had somehow recruited us—Ema, Spoon, Rachel, me—to help them rescue children and teens. This was never stated. We never applied for the job, and it wasn’t as though they had come to us. It just sort of . . . happened.

“I ask myself that every day,” I said.

“And?”

“I don’t know.”

“There has to be a reason,” Ema said. “First Ashley, then Rachel, and now—”

“Now what?”

“Someone else is missing,” she said.

My grip on the phone tightened. “Who?”

“You don’t know him.”

Silly, but I had thought that I knew everyone Ema knew. Maybe it was because she always played the big-girl-outcast-loner to perfection. The other kids made fun of her weight and her all-black clothes. Ema always sat by herself at lunch in the cafeteria. She had taken sullen and raised it to an art form.

“But you do?” I said.

“Yes.”

“Who?”

“He’s . . . well, he’s kind of my boyfriend.”

CHAPTER 6

Man, I hadn’t expected that answer.

How could I not know Ema had a boyfriend? How could she keep something like that from me? I mean, don’t get me wrong. I thought it was great. Ema was so awesome. She deserved somebody.

So why was I annoyed?

Because we told each other everything, didn’t we? Now I wasn’t so sure. I told her everything, but maybe it was just a one-way street. Clearly Ema hadn’t been equally forthcoming.

How could she not tell me that she had a freakin’ boyfriend?

Then again, had I told her about Rachel and me, about how there just might be something more between us?

No.

Why not? If Ema was just my friend—if it didn’t matter that she was a girl or whatever—why wouldn’t I tell her about Rachel?

“You okay?” Uncle Myron asked.

We were on the plane now, crammed next to each other in the last row. We are both tall, and the legroom in coach is designed for someone about two feet shorter.

“I’m fine,” I said.

“So now what?” Uncle Myron asked.

“What do you mean?”

“You asked me to help get your father’s grave exhumed, right?”

“Right.”

Uncle Myron tried to shrug, but the seat was too small for it. “So now that we’ve done that, what’s your next step?”

I had wondered that myself, of course. “I don’t know yet.”

• • •

As soon as we landed, I called Ema. No answer. I tried Rachel’s phone. No answer. I texted them both that I was back in New Jersey. I placed a call to the hospital again, trying to get through to Spoon’s room, but the operator wouldn’t patch the call through.

“No calls allowed to that room,” the operator explained.

I didn’t like that.

We had landed on time, which meant that I could still make basketball practice. I had missed the past few days because of this trip. That would set me back with the team, and it worried me a little. I hadn’t actually practiced with the varsity, and I knew that I would be way behind.

Kasselton High, my new school, has a varsity and junior varsity team. The varsity is for juniors and seniors. Freshmen and sophomores play JV, and so far, in Coach Grady’s dozen years of coaching the Kasselton Camels, he has never had a freshman or sophomore on the varsity.

Humble-brag alert: I, a lowly sophomore, have been invited to try out for the varsity team.

I couldn’t wait to get on the court, but as Uncle Myron pulled his car to a stop in front of the school, I felt the butterflies start flying around my stomach. Myron must have seen the look on my face.

“You nervous?”

“What, me?” I shook my head firmly. “No.”

Uncle Myron put his hand on my shoulder. “It may take a while to warm up after a long flight,” he went on, “but once you get on the court and the ball is in your hand—”

“Right, thanks,” I said, not really wanting to hear it.

It wasn’t worrying about my performance that stirred those butterflies.

It was my teammates. In short, they all hated me.

None of the seniors and juniors liked the idea of a lowly sophomore crashing their party.

I could hear laughter coming from the locker room, but as soon as I pushed open the door, all sound stopped as though someone had flicked a switch. Troy Taylor, the senior captain, glared at me. To put it mildly, Troy and I had issues. I looked away and opened a locker.

“Not there,” Troy said.

“What?”

“This row is for lettermen.”

Everybody else was in this row. I looked at the other guys. Some had their heads lowered, tying their shoes too carefully. Some glared with open hostility. I looked for Buck, Troy’s best friend and a total jerk, but he wasn’t there.

I waited for someone to stick up for me or, at least, comment. No one did. Troy smirked and made a shooing gesture in my direction with his hand. My face reddened in embarrassment. I wondered what I should do, whether I should fight or back down.

Not worth it, I decided.

I hated giving Troy the satisfaction, but I remembered something my father told me: Don’t win the battle and lose the war.

I took my stuff, moved into the next row, and changed into shorts and a reversible practice jersey. After I laced up my sneakers, I headed out to the gym. That sweet echo of dribbling basketballs calmed me a bit, but as soon as I opened the door, all dribbling stopped.

Oh, grow up.

There were four or five guys at each of three baskets. Troy shot at the one on the far right. His glare was already in place. I looked again for Buck—he was always with Troy, always following Troy’s lead—but he wasn’t here. I wondered whether Buck had gotten injured and, cruel as it sounded, I really hoped that was the case.

I looked toward the guys standing around the basket in the middle. If those faces were windows, they were all slammed shut with shades lowered. At the third basket, I spotted Brandon Foley, the team center and other captain. Brandon was the tallest kid on the team, six foot eight, and in the past, he had been the only one to acknowledge my existence. As I stepped toward him, he met my eye and gave his head a small shake.

Terrific.

The heck with it. I moved over to a basket in the far left corner and shot alone. My face burned. I let the burn sink deep inside of me. The burn was good. The burn would fuel my game and make me better. The burn would let me forget, for a few moments anyway, that I still didn’t know what really happened to my father. The burn would let me forget—no, not really—that my friend Spoon was in the hospital and may never walk again and that it was all my fault.

Maybe that explained why all my potential teammates, even Brandon Foley, had turned on me. Maybe they too blamed me for what happened to the nerd that they all enjoyed bullying.

It didn’t matter. Shoot, get the rebound, shoot. Stare at the rim, only the rim; never watch the ball in flight; feel the grooves on your fingertips. Shoot, swish, shoot, swish. Let the rest of the world fade away for a little while.

Do you have something like this in your life? Something you do or play that makes the entire world, at least for a little while, fade away? That was how basketball was. I could sometimes focus so hard that everything else ceased to exist. There was the ball. There was the hoop. Nothing else.

“Hey, hotshot.”

The sound of Troy’s voice knocked me out of my stupor. I looked around. The gym was empty.

“Team meeting for non-lettermen,” Troy said. “Room one seventy-eight. Hurry.”

“Where is that?”

Troy frowned. “You serious?”

“I’m new to the school, remember?”

“Lower level. Push through the metal doors. Hurry. Coach Grady hates when someone shows up late.”

“Thanks.”

I dropped the ball and hustled down the corridor. As I took the stairs down, a small niggling started at the back of my brain. It wondered how come Coach Grady would call a meeting so far from the gym. I wish that I had stopped there and listened to that niggling. But there was really no time. And what was I going to do anyway, run back upstairs and ask my buddy Troy for more details on the meeting?

So I ran down the corridor. There was no else in the halls. The echo of my sneakers slapping the linoleum sounded as loud as . . .

. . . as gunshots.

My head started spinning. Where exactly was I? The lower level was for senior classes. I had never been here before. But if my sense of direction was correct, I was pretty close to being right on top of where Spoon had been shot just a few days earlier.

I hurried my step.

Room 166. Then room 168. I was getting closer. 170, 172 . . .

Up ahead I saw the metal doors Troy had mentioned. I pushed through them. They closed behind me with a bang.

And locked me out.

I stopped and closed my eyes. There was no room 178. Practice was probably starting right now. I would have to go out the back, through the football field, and around to the front entrance in order to make my way to the gym.

I ran as fast as I could but it still took me nearly ten minutes to get back. My teammates were already doing the weave drill when I burst in through the door. Coach Grady was not pleased. He turned and snapped, “You’re late, Bolitar.”

“It isn’t my . . .”

I stopped. What exactly was I going to say here? Troy looked at me with that same stupid smirk. He knew. I had two choices. One, tell Coach Grady what really happened, in which case Coach Grady might or might not believe me, but either way I’d be forever labeled a tattletale. Or, two, keep my mouth shut.

“Sorry, Coach.”

But Coach Grady wasn’t done. “Being late to practice is disrespectful to both your teammates and your coaches.”

I nodded. “It won’t happen again.”

“You haven’t even made the team yet.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And this won’t help your cause.”

“I understand, sir. I’m really sorry.”

Coach Grady stared at me a beat too long. “Run three laps and then get on line. Troy?”

“Yes, Coach?”

“Where’s Buck?”

I would say that Buck was meaner than a snake, but that wouldn’t be nice to the snake.

“I don’t know, Coach. He didn’t pick up his cell.”

“Odd. He’s never missed a practice before. Okay, five-second-denial drill. Get into it.”

Practice didn’t get much better. Whenever we were working on plays, the guys would throw it at my feet, making it nearly impossible to catch. When we scrimmaged, they froze me out, never passing me the ball no matter how open I was. Of course, I got my share of rebounds. I scored twice off steals. But still. If your teammates freeze you out, there is only so much you can do.

And then, with just a minute left in practice, I saw a glorious opening.

I was covering Brandon Foley. He grabbed a rebound and threw a long outlet pass to Troy Taylor. Troy had been what we call “basket-hanging”—not playing defense and staying close to his own basket for easy points. Troy caught the ball and slowed down his dribble. He was taking his time, preparing for takeoff, revving himself up for a big-time slam dunk.

More in Series