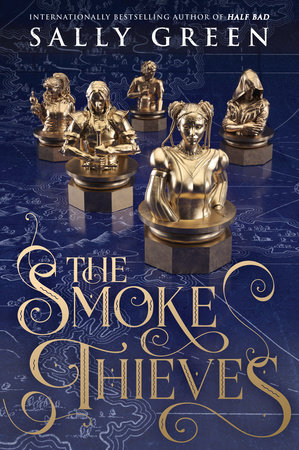

The Smoke Thieves

Part of: The Smoke Thieves

Ebook

$7.99

In a land tinged with magic and a bustling trade in an illicit supernatural substance, destiny will intertwine the fates of five players:

A visionary princess determined to forge her own path.

An idealistic solider whose heart is at odds with his duty.

A streetwise hunter tracking the most dangerous prey.

A charming thief with a powerful hidden identity.

A loyal servant on a quest to avenge his kingdom.

Their lives intersect with a stolen bottle of demon smoke. As war approaches, they must navigate a tangled web of political intrigue, shifting alliances, and forbidden love in order to uncover the dangerous truth about the strangely powerful smoke that interwines their fates.

“Hugely ambitious…. A rewarding read.” —The Times

"A YA Game of Thrones that pits power against love, conviction against convention."—Booklist

"A must-purchase."—School Library Journal

"The pieces that come together at the end are clearly only a part of a massive puzzle, teasing readers and ensuring a sequel." —BCCB Reviews

“Will hold readers rapt until the harrowing conclusion.” —Publishers Weekly

"Love, humor, politics, machinations, loyalty, violence, and magic swirl and shine in this fast-paced book that lovers of this genre will fall into and not want to climb out of." —School Library Connection

A Kids' Indie Next Selection

- Pages: 400 Pages

- Series: The Smoke Thieves

- Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

- Imprint: Viking Books for Young Readers

- ISBN: 9780425290231

An Excerpt From

The Smoke Thieves

THE SMOKE THIEVES

by Sally Green

TASH

Northern Plateau, Pitoria

“Everything Ready?”

“No. This is a figment of your imagination and I’ve been sitting on my arse all day eating honey.” Tash was adjusting the rope so its knotted end was a hand’s breadth above the bottom of the pit.

“A bit lower,” Gravell said. “I’m not blind! You need to check it.”

Tash turned on Gravell, “I know what I need to do!”

Gravell always got serious and persnickety at this stage and it only now occurred to Tash that it was because he was scared. Tash was scared too, but it didn’t help to think that Gravell wasn’t far off shitting in his pants as well.

“Not nervous, are you?” she asked.

Gravell muttered, “Why should I be nervous? You’re the one it’ll catch first. By the time it’s done with you I’ll be long gone.”

It was true, of course. Tash was the bait. She lured the demon into the trap and Gravell finished it off.

Tash was thirteen and had been demon bait since Gravell bought her from her family four years ago. He’d turned up one sunny day, the hugest, hairiest man she’d ever seen, saying he’d heard that they had a girl who was a fast runner, and told her he’d give her five kopeks if she could run to the trees before the harpoon he threw hit the ground. Tash thought it must be a trick—no one would pay just to see her run, and five kopeks was a huge sum—but she did it anyway, mostly to show off that she could. She wasn’t sure what she’d do with the money—she’d never had more than a kopek before and she’d have to hide it before her brothers took it off her. But she needn’t have worried; she left with Gravell that afternoon. Gravell gave her father ten kroners for her, he told her later. “A bit pricey,” he teased. No wonder her father had been smiling when she’d left.

Gravell was her family now, which was to Tash’s mind a lot better than the previous one. Gravell didn’t beat her, she was rarely hungry, and while she was sometimes cold, that was the nature of the work. And from the first day with Gravell she had been given boots. Yes, compared to her previous life, this one with Gravell was one of luxury and plenty. The money from selling demon smoke was good, although demons were rare and dangerous. The whole process of killing demons and selling smoke was illegal, but the sheriff’s men didn’t bother them if they were discreet. Gravell and Tash usually managed to catch four or five demons a season, and the money lasted the year and when they were in towns they stayed at inns, slept in beds, had baths, and, best of all, Tash had boots. Two pairs now!

Tash loved her boots. Her ordinary everyday boots were of thick leather with sturdy soles. Those were good for walking and hiking, and didn’t rub or pinch. She had no blisters and the smell from them she considered to be a good smell, more leathery than the stale sweat that Gravell’s boots oozed. Tash’s second pair, the pair she was wearing now, Gravell bought for her when they were in Dornan a few months earlier. These were her running boots and they fitted perfectly. They had sharp metal spikes in the soles so she could grip hard and set off fast. Gravell had suggested them and come up with the design, and he’d even paid for them—two kroners, which was a lot for boots. As she put them on the first time he’d said, “Look after them and they’ll look after you.” Tash did look after them and she definitely, absolutely refused to be ungrateful, but what she wanted, what she coveted more than anything in the world, were the ankle boots she’d thought Gravell was going to give her when he told her he was treating her to something special. She’d seen the ankle boots in the window of the cobbler’s shop in Dornan and mentioned them a few times to him. They were the most beautiful, delicate, pale gray boots of suede, so soft and fine that they looked to be made from rabbit’s ears.

When Gravell showed her the spiked boots and told her how he’d come up with the idea for them, she made a good job, she thought, of looking delighted. Tash told herself not to be disappointed. It would all work out. The spiked boots would help in this hunt and with the money from the demon kill she’d be able to buy the gray suede boots herself.

And soon they’d have their first demon.

Gravell found this demon’s lair after only a week. He’d dug the pit, though these days Tash set up and checked the escape mechanism and, in fact, wouldn’t let Gravell near it.

Gravell had taught Tash to be careful, to double-check everything and she went through a test run now, walking back from the pit a hundred paces, then jogging through the trees, picking up speed where there was little snow on the ground and into the small clearing where the snow was deeper but where she’d trampled it down to compress it so that it had hardened to a crisp, going at full speed now, pumping her legs, leaning forward, her spikes giving her grip but not holding her back, and then she was leaping over the edge of the pit, hitting the icy floor with a crunch, absorbing the drop with her knees but immediately getting up and running to the end and . . . waiting. Waiting.

That was the hardest part. That was the real shit-in-your- pants time, when your mind was screaming at you to grab the rope but you couldn’t because you have to wait for the demon to come down, and only when he was on the way down, just as he touched the bottom of the pit and screamed and screeched and slid toward you, could you grab the rope and release the pulley mechanism.

Tash pulled on the rope, bearing down on it with all her weight, her right foot resting on the lowest, thickest knot. The wooden release gave and Tash flew upward, as natural and lazy as a yawn, so balanced that her fingers were barely touching the rope and at the apex of her flight she stopped, hanging in the air, totally free, then she let go of the rope, leaned forward and reached for the fir tree, arms out to hug the branches, holding for another second before casually sliding down. A pine cone scratched her face and she landed almost knee deep in the pile of snow she’d banked there.

Tash walked back to reset the trap. Soil and footprints surrounded the pit; she’d have to clean the base of her boots to make sure they didn’t get clogged with dirt.

“You’re bleeding.”

Tash felt her cheek and looked at the blood on her finger- tips. Demons got more excited when they smelled blood. She licked her fingers and said, “Let’s get on with it.”

She grabbed the ropes and set the pulley back into place, satisfied that she’d done everything properly. The pulley was working smoothly. It was a good pit. Gravell had dug it over three days, making it long, thin and deep, and last night he and Tash had poured water down the steep sides until there was two hands depth in the bottom, which had frozen nicely to a hard, smooth ice. It was still possible to climb out of the pit—demons were good at climbing—and Gravell had over the years tried different ways to get the walls covered with ice too but it had never been that successful. So they would do what Gravell had always done and paint the pit walls with a mix of animal’s blood and guts. It smelled strong and disgusting and was enough to distract and confuse the demon, giving Gravell time to throw his harpoons. Gravell had five long harpoons, though it usually only took three to finish the demon off. They were specially made, each with a metal tip and teeth so they couldn’t be pulled out. The demon would scream and screech. The noise was horrible and Tash always had to remind herself that the demon would gladly do worse to her if he—it—caught her.

Tash looked up; the sun was still high in the sky. The demon hunt happened at the end of the day. She could feel her stomach begin to tighten with nerves now. She just wanted to get on with it. Gravell still had to coat the walls of the pit, then take cover in the nearby bushes and wait. Only when he saw the demon leap into the pit would he move for- ward, harpoons in hand. Timing was everything and they had it down to an art now, but it was Tash who risked her life, Tash who attracted the demon, Tash who had to know when to start running to draw the demon after her, Tash who had to outrun the demon, jump into the pit and, at the last possible moment, grab the rope and be hoisted out.

True, the demon could avoid the pit and attack Gravell. This had happened only once in their four years of demon hunting together. Tash wasn’t sure what had happened that day and Gravell didn’t talk about it. She’d leaped into the pit and waited, but no demon appeared. She’d heard Gravell shout; there was a high-pitched demon screech, and then silence. She hadn’t known what to do. If the demon was dead, why wasn’t Gravell shouting for her to come out? Did the screech mean the demon was wounded? Or was it the screech it made as it attacked and killed Gravell? Was the demon silent now because it was feasting on Gravell’s body? Should she run while the demon was drinking Gravell’s blood? She’d waited and looked up at the sky above the pit walls and realized she wanted a piss. She’d wanted to cry too.

She’d waited, holding on to the rope, but she was too terrified to move. Finally she’d heard something, a shuffling in the snow and Gravell shouted down: “Are you going to come out of there this year?” And Tash had tried to release the pulley but her hand was so cold and so shaky it took a while and Gravell was swearing at her by then. When she got out she was surprised to see that Gravell wasn’t wounded at all. He’d laughed when she crouched next to him, saying, “You’re not dead.”

After he laughed he went quiet and then he’d said, “Fucking demons.”

“Why didn’t it come into the pit?”

“I don’t know. Maybe it saw me. Smelled me. Sensed something . . . whatever it is they do.”

The demon was lying fifty paces from the pit with just one harpoon in its body. Had Gravell run or had the demon run? She had asked and all Gravell had said was, “We were both fucking running.” The other harpoons were speared into the ground at different points around them, as if Gravell had thrown them and missed. Gravell shook his head, saying, “Like trying to harpoon an angry wasp.”

The demon wasn’t much bigger than Tash. It was very thin, all sinew and skin, no fat at all; it reminded Tash of her older brother. Its skin was more purple than the usual reds and burned oranges, the sunset colors of the bigger demons. Within twenty-four hours the body would rot and melt away, the smell strong and earthy for that time, and then it would be gone, not even leaving a stain on the ground. There was no blood; demons didn’t have blood.

“Did you get the smoke?” Tash had asked.

“No. I was a bit busy.”

The smoke came out of the demon after it died. Tash wondered what Gravell had been busy doing, but she knew that he’d come close to death and saw that his hands were still trembling. She imagined that he must have killed the demon and tried to hold the bottle to catch the smoke but his hands had been shaking too much.

“Was it beautiful?”

“Very. Purple. Some red and a bit of orange to start but then all purple right through to the end.”

“Purple!” Tash wished she’d seen it. They had nothing to show for all their work, weeks of tracking, and then the days of digging and preparation. Nothing to show except their lives and stories of the beauty of demon smoke.

“Tell me more about the smoke, Gravell,” Tash had said. And Gravell told her how it had seeped out of the demon’s mouth—after the demon had stopped screeching. “Not much smoke this time,” Gravell added. “Small demon. Young maybe.” Tash had nodded. They’d lit a fire to get warm and in the morning, they’d watched the demon’s body shrink and disappear, and then they set off to find another.

Today’s demon was the first of the season. They didn’t hunt in winter, as it was too harsh, the snow too deep and the cold bitter. They’d come up to the Northern Plateau as soon as the deep snows began to melt, though this year spring had arrived but then winter returned for a few weeks and so there was still deep snow in the shade and in hollows. Gravell had found the demon’s lair and worked out the best place for the pit. Now Gravell lowered the pot of blood and guts into the pit and climbed down the ladder to paint the walls. Tash didn’t have to do this; Gravell had never asked her to—it was his job and he took pride in it. He wasn’t going to mess up weeks of work by failing to do this last task properly.

Tash sat on her pack and waited. She wrapped a fur round herself and stared at the distant trees and tried not to think any more about demons and the pit, so she thought of afterward. They’d go to Dornan and sell the demon smoke there. Trade in smoke was illegal, anything to do with demons was illegal, even setting foot on demon territory was illegal, but that didn’t mean there weren’t a few people like her and Gravell who hunted them, and it certainly didn’t stop people wanting to buy the demon smoke.

And once she had her share of the money she could buy her boots. Dornan was a week’s walk away, but the journey was easy and they’d enjoy warmth, rest and good food before returning to the plateau. Tash asked Gravell once why he didn’t collect more smoke and kill more demons, adding, “Southgate said Banyon and Yoden catch twice what we do each year.” But Gravell replied, “Demons is evil but so is greed. We’ve got enough.” And life was pretty good, as long as Tash kept running fast.

Eventually Gravell climbed back out of the pit, pulled the ladder up and put everything out of sight. Tash moved her pack to the trees. With that done, there was nothing left to prepare. Gravell circled the pit a final time, muttering to him- self, “Yep. Yep. Yep.”

He came over to Tash and said, “Right then.”

“Right then.”

“Don’t fuck up, missy.”

“Don’t you neither.”

They knocked right fists together.

The words and fist bump were a ritual they had for good luck, though Tash didn’t really believe in luck and was fairly sure Gravell didn’t either but she wasn’t going to go through a demon hunt without all possible assistance on her side.

The sun was lower in the sky and soon the sun would be below the level of the trees, the time when it was best to lure the demon out. Tash jogged north, through thin woodland, to the clearing that she and Gravell had found ten days earlier. Well, Gravell had found it. That was his real skill. Digging pits and lining them with guts anyone could do, his knack for killing demons with harpoons was due to his size and strength, but what made Gravell very special was his patience, his instinctive ability to find the places demons lived. Demons liked shallow hollows on flat ground, not too close to trees, where mist collected. They liked the cold. They liked snow. They didn’t like people.

Tash used to ask Gravell all about demons but now she probably knew as much as anyone could about something from a different place. And what a place it was. Not of this earth, she thought, or perhaps too much of this earth, of an ancient earth. Tash had seen into it, the demon land: that was what she had to do. To lure the demon out she had to venture in, where she was not allowed, where humans didn’t go. And the demons would kill her for daring to see their world, a world that was bruised and brooding. Not so much dark as a different type of light; the light was red and the shadows redder. There were no trees or plants, just red rock. The air was warmer, thicker, and then there were the sounds.

Tash waited until the sun was halfway below the hill, the sky red and orange only in that small section. Mist was collecting in the gentle hollows. It was forming in her demon’s hollow too. This hollow was slightly deeper than the other dips and undulations around it, but unlike the rest this had no snow in it, and at this time of evening the mist could be seen to have a tinge of red, which perhaps could be due to the sunset, but Tash knew otherwise.

Tash approached slowly and silently and knelt at the rim of the hollow. She reached back to clean the spikes on her boots with her fingers, pulling off a few small clumps of earth. She put her hands on the ground and spread her fingers, feeling the earth, which was not warm but was not frozen solid either—this was the edge of demon territory.

She dug in her toes and took a breath as if she was about to submerge, which in a way she was. Tash lowered her head, and with eyes open she pushed her head forward, her chest brushing the ground, as if she was nosing under a curtain into the hollow: into the demon’s world.

Sometimes it took two or three attempts, but today she was in first time.

The demon land fell away before her, the hollow descending sharply to a tunnel, but that wasn’t the only thing that was different from the human world. Here, in the demon world, colors, sounds and temperatures were altered, as if she was looking through a colored glass into an oven. Describing the colors was hard, but describing the sounds was impossible.

Tash looked across the red hollow to the opening of the tunnel, and there at the lowest point was something purple. A leg?

Then she made sense of it and saw that he—it—was sprawled on its stomach, one leg sticking out. Tash worked out its torso, an arm and its head. Human-shaped but not human. Skin smooth and finely muscled, purple and red and streaks of orange, narrow and long. It looked young. Like a gangly teenager. Its stomach was moving slowly with each of its breaths. It was sleeping.

Tash had been holding her own breath all this time and now she let out what air she had. Sometimes that’s all she needed to do; just her breath, her smell, would get the demon’s attention.

This demon didn’t move.

Tash took a breath in, the air hot and dry in her mouth. She shouted her shout: “I’m here, demon! I can see you!” But her voice did not sound the same here. Here, words were not words but a clanging of cymbals and gongs.

The demon’s head lifted and slowly turned to face Tash. One leg moved, bending at the knee, the foot raising in the air, totally relaxed despite the intrusion. The demon’s eyes were purple. It stared at Tash and then blinked. Its leg was still in the air and was totally still. Then it threw its head back, lowered his leg, opened its mouth and stretched its neck to howl.

A clanging noise hit Tash’s ears as the demon sprang up and forward, purple mouth open, but already Tash was springing up too, pushing her spikes hard into the ground and twisting round in the air in a leap that took her out of the demon world and back on to the lip of the hollow, back into the human world.

And then she was running.

CATHERINE

Brigane, Brigant

There is no greater evil than that of a traitor. All traitors must be sought out, exposed and punished.

• -The Laws and Devices of Brigant

“Boris has sent a guard to escort us there, Your Highness.” Jane, the new maid, looked and sounded terrified.

“Don’t worry. You won’t have to watch.” Catherine smoothed her skirt and took a deep breath. She was ready.

They set off: the guard ahead, Catherine in the middle and Jane at the rear. The corridors were quiet and empty in the queen’s part of the castle; even the guard’s heavy footsteps were hushed on the thick rugs. But entering the central hall was like crossing into a different world: a world full of men, color and noise. Catherine so rarely came into this world that she wanted to take it all in. The lords were in breastplates, with swords and daggers, as though they didn’t dare come to court without appearing their strongest. Numerous servants stood around and everyone seemed to be talking, looking, maneuvering. Catherine recognized no one, but the men recognized her and parted to allow her through, the noise quietening around her then building again as she passed.

And then she was at another door, which the guard held open for her. “Prince Boris asked that you wait for him in here, Your Highness.”

Catherine entered the ante hall, indicating with a wave of her hand that Jane should wait outside the door, which was already being closed.

It was quiet, but Catherine could hear her own heart beating fast. She took a deep breath and let it out slowly.

She told herself, Stay calm. Stay dignified. Act like a princess.

She straightened her back and took another deep breath.

Then paced slowly to the far end of the room.

It’ll be ugly. It’ll be bloody. But. I won’t flinch. I won’t faint.

I certainly won’t scream.

And back again.

I’ll be controlled. I won’t show any emotion. If it’s really bad I’ll think of something else. But what? Something beautiful? That would just be wrong.

And back again.

What do you think of when you watch someone having their head chopped off? And not just anyone but Amb–

Catherine turned and there was Noyes, somehow in the corner of the room, leaning against the wall.

Catherine rarely met Noyes but whenever she saw him she had to suppress a shudder. He was slim and athletic, probably the same age as her father. Today he was fashionably dressed in his leather and buckles, his shoulder-length, almost white hair tied back from his angular face in fine plaits and a simple knot. But for all that there was something un- pleasant about him. Maybe it was just his reputation. Noyes, the master inquisitor, was in the business of seeking out and hunting down traitors. He didn’t kill prisoners himself for the most part; that was the job of his torturers and executioners. In the seven years since the war with Calidor, Noyes and his like had flourished, unlike most Brigantine businesses. No one was safe from his scrutiny: from stable lad to lord, from maid to lady, and even to princess.

Noyes pushed off the wall with his shoulder, took a lazy step toward her, made a slow bow and said, “Good morning, Your Highness. Isn’t it a beautiful day?”

“For you, I’m sure.”

He smiled his half-smile and remained still, watching her. Catherine asked, “Are you waiting for Boris?”

“I’m merely waiting, Your Highness.”

They stood in silence. Catherine looked up at the high windows and the blue sky beyond. Noyes’s eyes were on her and she felt like a sheep at a market . . . no, more like an ugly bug that had crawled across his path. She had an urge to scream that he should show her some respect.

She turned abruptly away from him and told herself, Stay calm. Stay calm. She was good at hiding her emotions after nearly seventeen years of practice, but recently it had become harder. Recently her emotions kept threatening to get the better of her.

“Ah, you’re here, sister,” Boris called as he barged through the doors, Harold trailing in his wake. For once Catherine was relieved to see her brothers. She curtsied. Boris strode through the room, ignoring Noyes and not even bowing to Catherine. He didn’t come to a standstill, but carried on, saying, “Your maid stays here. You come with me.” He pushed open the double doors into the castle square, saying, “Come on, sister. Don’t dilly-dally.”

Catherine hurried after Boris, the doors already swinging shut in her face. She pulled them open and was relieved that Boris had stopped, the scaffold ahead of them was almost blocking the way, as tall as the rose-garden wall.

Boris snorted a laugh. “Father told them to make sure everyone gets a good view, but I swear they’ve cut down an acre of forest to build this.”

“Well, I don’t know why she should get to see it. This isn’t for girls,” Harold said, hands on hips, legs apart, staring at Catherine.

“And yet children are allowed to attend,” Catherine replied, imitating his stance.

“I’m fourteen, sister.”

Catherine walked past him, whispering, “In two months, little brother. But I won’t tell anyone.”

Harold grumbled, “I’ll soon be bigger than you,” before pushing past her and stomping off after Boris. He looked particularly small and slight as he followed behind Boris’s broad frame. They were clearly brothers, their red-blond hair exactly the same shade, though Harold’s was more intricately tied and it struck Catherine that he must have had someone spend more time on his hair than her maids had spent with hers.

However, Harold’s opinion about the propriety of Catherine’s presence mattered as much as Catherine’s own. She had been ordered to attend the execution by her father, on the advice of Noyes. Catherine had to prove herself to them. Prove her strength and loyalty, and most importantly that she was no traitor in heart, mind or deed.

Boris was already rounding the corner of the scaffold. Catherine hurried to catch up, lifting her long skirt so as not to trip. Although she couldn’t yet see the crowd, she could hear its low buzz. It was strange how you could sense a crowd, sense a mood. The men in the hall had been polite on the surface but there was a barely concealed lust: for power, for . . . anything. Here, there was a large crowd and a surprisingly good mood. A couple of shouts of “Boris” went up but they quickly died. This wasn’t Boris’s day.

Boris turned and stared at Catherine as she joined him. “You want to show off your legs to the masses, sister?”

Catherine dropped her skirt and smoothed the fabric, saying in her most repulsed voice, “The cobbles aren’t clean. This silk will be ruined.”

“Better that than your reputation.” Boris held Catherine’s gaze. “I’m only thinking of you, sister.” He waved to his left, at the raised platform carpeted in royal red, and stated, “This is for us.”

As if Catherine couldn’t work it out for herself.

Boris led the way up the three steps. The royal enclosure was rather basic, with a single row of the wide, carved wooden stools Catherine recognized from the meeting hall. A thick red rope was strung loosely between short red and black posts that demarked the platform. The crowd was beyond the platform and it too was held back by rope (not red, but thick, coarse and brown) and a line of king’s guards (in red, black and gold, but also thick and coarse, Catherine assumed).

Boris pointed at the seat closest to the far edge of the plat- form. “For you, sister.” He planted himself on the wide stool next to hers, his legs apart, a muscular thigh overlapping Catherine’s seat. She sat down, carefully arranging her skirt so that it wouldn’t crease and so that the pale, pink silk fell over Boris’s knee. He moved his leg away.

Harold remained standing by the seat on the other side of Boris. “But Catherine gets the best view.”

“That’s the point, squirt,” Boris replied.

“But I have precedence over Catherine and I want to sit there.”

“Well, I gave Catherine that seat. So you sit on this one here and shut up.”

Harold hesitated for a second. He opened his mouth to complain again but caught Catherine’s eye. She smiled and made an elegant sewing sign in front of her lips. Harold glanced at Boris and had to clamp his lips together with his teeth, but he did remain quiet.

Catherine surveyed the square. There was another platform opposite, on the other side of the scaffold, with some noblemen standing on it. She recognized Ambrose’s long blond hair and quickly looked away, wondering if she was blushing. Why did just a glimpse of him make her feel hot and flustered? And today of all days! She had to think of something else. Sometimes her whole life seemed to involve thinking of something else.

The area before the scaffold was packed with common folk. Catherine stared at the crowd, forcing her focus on to them. There were scruffily dressed laborers, some slightly smarter traders, groups of young men, some boys, few women. They were for the most part dressed drably, some almost in rags, their hair loose or tied back simply. Near her people were talking about the weather. It was already hot, the hottest day of the year so far, the sky a pure pale blue. It was a day to be enjoyed and yet hundreds of people were here to see someone die.

“What makes these people come to watch this, do you suppose, brother?” Catherine asked, putting on her I’m-asking-a-genuine-question voice.

“You don’t know?”

“Educate me a little. You are so much more experienced in these matters.”

Boris replied in an overly sincere voice, “Well, sister. There’s a holy trinity that drives the masses and draws them here. Boredom, curiosity and bloodlust. And the greatest of these is bloodlust.”

“And do you suppose this bloodlust is increased when it’s a noble head that is going to be severed from a noble body?”

“They just want blood,” Boris replied. “Anyone’s.”

“And yet these people here seem more interested in discussing the weather than the finer points of chopping someone in two.”

“They don’t need to discuss it. They need to see it. They’ll stop talking about the weather soon enough. When the prisoner is brought out you’ll see what I mean. The rabble want blood and they’ll get it here today. And you’ll get a lesson in what happens to someone who betrays the king. One you can’t learn from books.”

Catherine turned her face from the contempt in Boris’s voice. That was how she learned about life—from books. Though it was hardly her fault that she wasn’t allowed to meet people, to travel, to learn about the world from the world. But Catherine did like books and in the last few days she had scoured the library for anything relating to executions: she’d studied the law, the methods, the history and numerous examples. The illustrations, most of which showed executioners holding up severed heads, were bad enough, but to choose to witness it, to choose to be part of it, part of the crowd baying for blood, was something Catherine couldn’t understand.

“I still don’t see why Catherine needs to be here at all,” Harold complained.

“Didn’t I tell you to shut up?” Boris didn’t even turn to Harold as he spoke.

“But ladies don’t normally come to watch.”

Boris now couldn’t resist replying, “No, not normally, but Catherine needs a lesson in loyalty. She needs to under- stand the consequences of not following our plans for her.” He turned to Catherine as he added, “In every aspect. To the smallest degree.”

Harold frowned. “What plans?” Boris ignored him.

Harold rolled his eyes and leaned toward Catherine to ask, “Is this about your marriage?”

Catherine smiled thinly. “This is an execution, so why you would link it to my marriage, I can’t imagine.” Boris glared at her. “What I mean is, I’m honored to be marrying Prince Tzsayn of Pitoria and will ensure every aspect of the wedding goes to plan, whether or not I see someone having their head chopped off.”

Harold was quiet for a few moments before asking, “But why wouldn’t it go to plan?”

“It will,” Boris answered. “Father won’t let anything stop it.”

This was true, and Catherine’s complete obedience to every detail of the plan was required, and that was why she was here. She had made the mistake a week earlier of saying to her maid, Diana, that Diana could perhaps look forward to a marriage based on love. Diana had asked Catherine whom she would marry if she could choose, and Catherine had joked, “Someone I’ve spoken with at least once.” Adding, “Someone intelligent and thoughtful and considerate.” As she said it, she had thought of her last conversation with Ambrose as he escorted her on her ride. He had joked about the quality of food in the barracks, then had grown serious as he described the poverty in the backstreets of Brigane. Diana seemed to know her thoughts and had said, “You spoke with Sir Ambrose at length this morning.”

The following day after the conversation with Diana, Catherine was summoned to Boris and that was when she’d realized her maid was less her maid and more Noyes’s spy. Catherine suffered lengthy lecturing and questioning from Boris, but it was Noyes who listened most closely to her answers, though he made a show of leaning against the wall and yawning occasionally. Noyes was not even a lord, hardly a gentleman, but the way his lips curled in a half-smile made Catherine’s skin crawl and she feared him twice as much as her brother. Noyes was her father’s presence, his spy, his eyes and ears. Boris was that too of course, but Boris was always bludgeoningly obvious.

At the interview, Boris had repeated the usual lines about unquestioning loyalty and obedience and Catherine had been pleased with how cool she’d remained.

“I am merely nervous, as any bride-to-be is before their wedding. I have never even met Prince Tzsayn. Just as I try to be the best daughter I can be to Father, I hope to be a good wife to Tzsayn, and to be that I look forward to talking to him, getting to know him, finding out about his interests.”

“His interests are of no concern to you. What is of interest and concern to me is that you do not express an opinion that counters that of the king.”

“I’ve never expressed any opinion that doesn’t agree with Father’s.”

“You implied to your maid that your marriage could be improved upon and that you don’t wish to marry Prince Tzsayn.”

“No, I merely said that Diana’s marriage could be successful in a different way.”

“To disagree with the king’s plans for you is unacceptable.”

“I’m disagreeing with you, not with the king’s plans for me.”

“I often wonder,” Noyes interrupted, “at what point a traitor is made. When precisely the line is crossed between loyalty and betrayal.”

Catherine straightened her back. “I have crossed no line.” And she hadn’t: she had done nothing, except think of Ambrose.

“In my experience . . . and, Princess Catherine, I do consider my experience in this area to be considerable,” murmured Noyes. “In my experience, a traitor in the heart and mind is soon a traitor in deed.”

And the way he looked at her it felt as if he truly could see inside Catherine’s head. But she stared back at him, saying, “I am no traitor. I will marry Prince Tzsayn.” Catherine knew this to be true. She would soon be married to a man she’d never even met, but she couldn’t help her mind and her heart belonging elsewhere. Couldn’t help that she thought of Ambrose constantly, loved her conversations with him, contrived to be close to him and, yes, had once touched his arm. Of course, if Ambrose touched her, he’d be executed, but she didn’t see why she couldn’t touch him. But were these thoughts and one touch really traitorous deeds?

“It’s best to be clear where the line is, Princess Catherine,” Noyes said quietly.

“I’m clear, thank you, Noyes.”

“And also to be clear on the consequences.” He waved his hand casually, almost dismissively. “And to that end you are required to attend the execution of the Norwend traitor, and witness what happens to those who betray the king.”

“A punishment, a warning and a lesson, all rolled neatly into one.” Catherine mimicked Noyes’s hand wave.

Noyes’s face was blank as he replied, “It’s the king’s command, Your Highness.”

Sadly Diana had had a nasty trip down some stone stairs the day after Catherine’s interview and had been unable to resume her duties because of a broken arm. Catherine’s other maids, Sarah and Tanya, had been with Diana at the time but somehow had been unable to prevent the accident. “We agree with Noyes, Your Highness,” Tanya had said with a smile. “Traitors should be punished . . .”

Catherine was brought back to the present by shouts from the crowd: “Bradwell! Bradwell!”

Two men had come up the steps on to the scaffold, both dressed in black. The older man held up his hand to the people. His young and surprisingly cherubic assistant carried the tools of their trade, a sword and simple black hood.

“It’s Bradwell,” Harold said unnecessarily, leaning over Boris to Catherine. “He’s carried out over a hundred executions. A hundred and forty-one, I think it is. And he never takes more than one strike.”

“A hundred and forty-one,” Catherine echoed. She wondered how many of them Harold had witnessed.

Bradwell was walking across the scaffold, swinging his sword arm as if warming up his shoulder muscles, and flex- ing his head from side to side and then round. Harold rolled his eyes. “Shits, he looks ridiculous. Gateacre should have been given the job.”

“I believe the Marquess of Norwend requested Bradwell and the king obliged,” Boris said. “Norwend wanted it done cleanly and seemed to think Bradwell was best. But there are no guarantees on that score.”

“Gateacre has a clean cut too,” Harold said.

“I agree. He would have been my choice. Bradwell is looking rather past it. Still, it might add another level of interest if he botches the job.”

At the mention of the Marquess of Norwend, Catherine’s gaze had moved to the opposite side of the scaffold to the other raised viewing platform. She had felt it too risky to discuss the people there unprompted, but now that Boris had brought the subject up she felt she could ask, “Is that the Marquess of Norwend on the other platform, in the green jacket?”

“Indeed. And all the Norwend clan with him,” Boris replied. Though Catherine noted it was only the male members of the family. “The traitor’s kin must witness the execution; indeed, they must call for the traitor’s death or they will lose their titles and all their lands.”

Catherine knew the law well enough. “And what of their honor?”

Boris snorted. “They’re trying to cling on to that, but if they can’t even control one of their own they’ll struggle to maintain their position at court.”

“Honor and position at court being one and the same,” Catherine replied.

Boris looked at Catherine as he said, “As I said, they’re barely clinging on to either.” He turned back to the opposite platform adding, “I see your guard is with them, though thankfully he’s not in uniform.”

Catherine didn’t dare comment. Was Ambrose not wearing the Royal Guard’s uniform as a mark of respect for royalty or disrespect for them? She knew he had his own views on honor. He talked of doing the right thing, of wanting to defend Brigant and of helping make the country great again, not for self-gain but to help all in the country who were suffering in poverty.

She had noticed Ambrose when she’d taken her seat and had forced herself to turn away, but now Boris had mentioned him she could allow herself a slightly longer look. His hair, golden white in the sunlight, was loose and falling in soft waves around his face and shoulders. He was wearing a black jacket with leather straps and silver buckles, black trousers and boots. His face was solemn and pale. He was staring at the executioner and hadn’t shifted his gaze toward Catherine since her arrival.

Catherine looked at Ambrose for as long as she would an ordinary man, then she made herself turn away, but still his image lingered in her head: his hair, his shoulders, his lips . . . A flurry of courtiers appeared from behind the scaffold.

From the way they were stepping back and bowing, it was obvious that her father was on his way. Catherine’s heart beat erratically. She had lived a sheltered life in the queen’s wing of the castle with her mother and maids, going weeks or months without seeing her father. For her, his one and only daughter, his presence was still an occasion.

The king appeared, walking quickly, his red and black jacket emphasizing his wide shoulders, his tall hat adding to his height. Catherine rose swiftly to her feet and demurely lowered her head as she sank into a deep curtsy. She was on a platform above the king but her head should be lower than his. Tall as her father was, it was still a contortion. Catherine held her stomach tight and thighs tense in a semi-crouch. Her corset dug sharply into her waist. She concentrated on the discomfort, knowing she’d outlast it. Out of the corner of her eye she could see the king. He leaped on to the royal platform, strode forward and the crowd, on seeing him clearly, cheered and a long slow shout went up, “A-lo-ys-ius! A-lo-ys-ius!”

Boris rose from his bow and Catherine waited the required two extra counts before lifting her head. The king was motionless, looking to the crowd, and he didn’t acknowledge Catherine at all. Then he sat on the seat next to Harold, red cushions having appeared moments before to ease his royal rump. Catherine stood, feeling the relief in her stomach. Harold too had straightened from his bow and stood stiffly, hesitating before sitting, though Catherine was sure he’d be delighted to be next to the king. She waited for Boris to sit and then she straightened her skirt and retook her own place.

Things moved quickly now. The king wasn’t noted for his patience after all. More men ascended the scaffold. There were four men in black and four in guard uniforms and, barely seen among them, diminished, small and frail, was the prisoner.

The crowd jeered and shouted, “Traitor!” Then, “Whore!” and “Bitch!” and worse, much worse.

There were words Catherine knew and had occasionally come across in reading but had never heard spoken, not even by Boris, and now they were flying through the air around her. They were more powerful than she’d known words could be, and they were not beautiful, poetic or clever, but base and vulgar, like a slap in the face.

Catherine caught a glimpse of Ambrose, still and stiff opposite her, his face contorted as the crowd jeered and insulted his sister. Catherine shut her eyes.

Boris hissed in her ear, “You’re not looking, princess. You’re here to see what happens to traitors. It’s for your own good. So, if you don’t turn to face the scaffold, I’ll pin your eyes open myself.”

Catherine didn’t doubt Boris’s sincerity. She opened her eyes and turned back to the scaffold.

Lady Ann Norwend was dressed in a gown of blue silk with silver lace. Her jewels sparkled in the sunlight and her blonde hair, pinned up, glowed gold. In normal times, Lady Ann was considered beautiful, but today was far from normal. Now she was painfully thin, her skin pale, and she was held upright by two guards. But most noticeable of all was her mouth: thick black lines of twine stretched from her top lip to her bottom where her mouth had been sewn up, and dried blood covered her chin and neck. Her tongue had already been cut out. Catherine wanted to look to Ambrose, but didn’t dare turn to him, couldn’t bear to see him again. What must he be thinking to see his sister like this? Catherine stared in the direction of Lady Ann and found the way to do it was to concentrate on the guard holding her up, and how fat his fingers were and how tight his grip was.

The king’s speaker stepped forward to address the crowd, demanding silence. When the din subsided, he began reading from a scroll, listing Lady Ann’s crimes. “Luring a married man into temptation” referred to her relationship with Sir Oswald Pence. “Failing to attend on the king when requested” meant fleeing with Sir Oswald when Noyes and his men confronted them. “Murder of the king’s men” meant just that and, hard as it was to believe looking at Lady Ann now, she had herself stabbed one of the king’s soldiers in the fight that left three dead including Sir Oswald. The murder was the key reason she was to be executed; murder of one of the king’s men was tantamount to killing the king himself— it was high treason, and so, to round his speech off, the speaker said, “And for being a traitor to Brigant and our glorious king.”

The crowd went wild.

“The traitor, murderer and whore is to be stripped of all possessions, which are forfeit to the king.”

One of the black-clothed men approached Lady Ann and began removing her jewels one by one. Each time he took an item—a brooch, a ring, a bracelet—there were cheers and shouts from the crowd. Each item was put into a casket held by another man. When the jewels were all removed, that man took a knife and cut the back of her dress, and a fresh cheer from the crowd rose as the gown was ripped from her shoulders. Lady Ann was almost dragged off her feet, but the guard pulled her upright and held her. The crowd bayed again like a pack of hounds and began a chant of “Strip! Strip! Strip!”

Lady Ann was left in her underdress, clutching its thin fabric to her chest. Her hands were shaking and Catherine could see that her fingers were misshapen and broken. At first she didn’t understand why, but then realized that was part of the ritual of a traitor’s execution. Those condemned for treason were not allowed to communicate with the king’s loyal subjects and so had their tongues cut out, their lips sewn up. But, as all court ladies in Brigant used hand signs to speak to each other when they were not allowed to use words, Lady Ann had had her hands broken too.

One of the men loosened Lady Ann’s hair, which was long and fine and the palest of yellows. He took a handful and cut it at the nape of her neck. He held the hair and that too went in the casket. Finally she was left near naked, shivering despite the summer sun, the tattered gown almost transparent and clinging to her legs where she had wet herself. It seemed even Lady Ann’s dignity was forfeit to the king.

Turning from Lady Ann, the speaker called to the plat- form opposite, “What do you say to this traitor?”

Her father, the marquess, a tall, gray-haired man, came forward. He straightened his back and cleared his throat.

“You have betrayed your country and your glorious king. You have betrayed my family and myself, all loyal sub- jects who have nurtured you and trusted you. You have betrayed my trust, and my family’s name. It would have been better if you had not been born. I denounce you and call for your execution as a traitor.”

Catherine looked for Lady Ann’s reaction. She stared back at her father and seemed to stand more upright. In turn, five other male relatives—her two uncles and two cousins and her elder brother, Tarqin, who was close in looks to Ambrose with the same blond hair—came forward and shouted their denouncements of a similar kind and called at the end for her execution. After each censure the crowd cheered and then went silent for the next person. And after each one Lady Ann seemed to grow in strength and stature. At first Catherine was surprised at this, but she too began to sit taller. The more they demeaned Lady Ann, the more she wanted to show them how strong she was.

The last to step forward was Ambrose. He opened his mouth but no words came out. His brother leaned toward him and spoke. Catherine could read Tarqin’s lips as he said, “Please, Ambrose. You have to do it.”

Ambrose took a breath before saying in a voice that was clear but hardly raised, “You are a traitor to Brigant and the king. I call for your execution.” His brother put his hand on Ambrose’s shoulder. Ambrose continued staring at Lady Ann as tears rolled down his cheeks. The crowd didn’t cheer.

Boris said, “I do believe he’s weeping. He’s as weak as a woman.”

However, Lady Ann was not crying. Instead, she made a sign: her hand on her heart, the simple sign of love for Am- brose. Then she turned and her eyes met Catherine’s. Lady Ann moved her right hand up as if to wipe a tear, as her left hand went to her chest. It was a movement so smooth, so disguised, it was hardly noticeable. But Catherine had been reading signs since childhood and this was one of the first she had learned. It meant “Watch me.” Then Lady Ann made the sign of a kiss with her right hand, while her left swept downwards and clenched into what looked like an attempt at a fist. Catherine frowned. A fist held before the groin was the sign of anger, hate, a threat. To pair it with a kiss was strange. Then another sign: “boy.” Lady Ann turned to stare at the king and was making another sign, but the man holding her arm had moved in the way.

Catherine didn’t know Lady Ann; she’d never spoken to her, had seen her in court only once. Catherine was confined to her quarters for so much of her life that seeing other women was hardly more common than seeing and talking to men. Had she imagined the signs?

Lady Ann was brought forward and forced to kneel on a low wooden block. She looked down, and then turned so her eyes met Catherine’s again, and there was no mistaking their intensity. What was she trying to say, at the very moment of her death?

Bradwell, the executioner, was wearing his hood now but his mouth was still visible, and he said, “Look ahead or I can’t guarantee it’ll be clean.”

Lady Ann turned to face the crowd.

Bradwell raised the sword above his head and the sunlight bounced off it into Catherine’s eyes. The crowd hushed. Bradwell came a step forward and then to the side, perhaps to assess the angle of his cut, then he went behind Lady Ann, circled the sword in the air over his own head once, took a half step forward, swirled the sword over his head once more, and in a continuous movement made a sideways slice so fast that it appeared for a moment as though nothing had happened.

Lady Ann’s head fell first, hitting the wooden floor with a thud, and then rolled to the edge of the scaffold. Behind it, blood fanned from the neck of the slowly toppling body. The crowd’s cheer was like a physical blow and Catherine swayed back on her seat.

Bradwell moved forward, retrieved the head and held it up by the hair. A chant of “Pike her” went up. Bradwell’s assistant stepped forward with a pike and the crowd’s frenzy increased further.

Somehow, across the scaffold and the roaring mob, Catherine’s eyes met Ambrose’s. She held his gaze, wanting to comfort him, to tell him she was sorry. She needed him to know that she was not like her father or her brother, that she didn’t choose to be here, that despite the impossible distance between them she cared.

Boris hissed in her ear, “You’re not looking at Lady Ann, sister.”

Catherine turned. Lady Ann’s head was being put on a pike, and there was Noyes standing at the foot of the scaffold, a half-smile on his lips as he turned his attention from her to Ambrose. And Catherine realized she’d been a fool: this wasn’t a punishment, a warning or a lesson.

It was a trap.

More in Series