A Queen of Gilded Horns

Paperback

$10.99

More Formats:

- Pages: 384 Pages

- Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

- Imprint: G.P. Putnam's Sons Books for Young Readers

- ISBN: 9780525518631

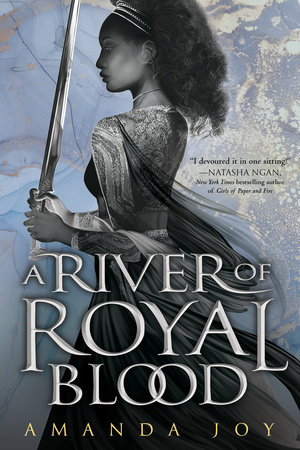

An Excerpt From

A Queen of Gilded Horns

Eva

I dream of fire. A river of blood and a column of smoke rising so dark and thick as to blot out the sun.

I dream of gnashing blades and crunching teeth and the foul reek of viscera spilled upon marble floors. I dream of a knife buried in my chest and a crimson crown balanced atop Isadore’s golden brow. I dream of the Hunter in chains, eyes red-rimmed with sorrow, shackles wearing down his flesh to the bone. I dream of Court and coronations and fine silk and gossamer gowns drenched in gore.

I dream of the Patch and chatara and my bare feet dancing upon the broken paving stones until they run with blood.

I dream and dream and dream, conjuring every darkness seeded deep within me. It feels like magick, this dreaming. In my waking hours when everyone seems to watch me from the corner of their eyes, worried I will finally show signs of breaking, I know my dreams have protected me. I can smile and pretend for them, waiting for night when I will wake screaming and only Aketo will be there to see.

At least I had the dreaming; much as the terror ate me up inside at night, by day it bolstered me. Look, see how I could seethe and weep and be so afraid and, yet, come morning I could hold it all in with a will of steel and a biting smile.

Because I couldn’t afford to be broken.

Not when I’d stolen my sister halfway across the Queendom to keep my mother from crowning her when the truth of my heritage spread. Not when I had dragged half my guard along with me, making them betray their oaths to the throne. Not while I sought a way to keep all of us safe, Isadore included. Not while I needed to soon decide what my future would hold.

There could be no breaking under such circumstances.

I had to find a way to survive first.

---

I inched forward on my elbows, eyes slit against the cloud of golden soil that rose at our every move. The sky above was an unbroken stretch of cerulean and the midday sun hammered against my back, but anything that dulled the bite of the wind that swept through these lowlands had my gratitude. The bare skin on my arms pebbled as another gust rolled past, tugging apart the loose braid at the nape of my neck.

High Summer was well and truly gone, but by virtue of my greatly diminished wardrobe, I hadn’t yet given up the sleeveless tunics and thin leggings of the warm months.

It had been six weeks since my nameday on the last day of High Summer, and what little warmth left in the year still lingered on the Plain. A chill had begun to flow south. Autumns were long in Myre, the land slow to cool for a short and bitter Far Winter.

Far Winter being the season when cold came down from the A’Nir Mountains all the way to the Red River. Soon the silks and cottons of High Summer and autumn would be exchanged in favor of wool and furs. And most of the clothing I’d brought from Ternain would be of little use.

If we stayed in the North on the path I had set.

That remained to be seen, considering we’d been stuck for the last week, waiting.

As the dirt settled, I peered through the battered eyeglass I’d acquired three weeks ago before venturing onto the Plain. I blinked, gaze focusing on the small village that lay just a few miles north. From our vantage point atop a rock outcrop that jutted up from the Plain like a tooth—more a misshapen molar than the smaller, fang-shaped stones that dotted the vast golden plain—I could cup the village in my palm. Anali and I pressed flat to the ground, hiding in a fold in the rock that kept the few villagers going about their day from spying us.

Arym meant “gold” in Khimaeran, and the Plain had been named for the bright ocher dirt that glittered faintly in the sun. It was a hard region, with hundreds of miles of flat grasslands, shallow lakes fed from an offshoot of the Red River that ran deep beneath the earth, and low, lifeless hills peppered with undersize, knotty trees. Few traversed the Arym Plain for fear of the lions and magickal predators that roamed it. Not to mention the roving herds of wildebeest and antelope and Gods knew what else. Any land left to grow wild and free in Myre kept secrets even the oldest storybooks didn’t speak of.

But even shining dirt couldn’t pretty up the small village curled up in the shadow of a considerable estate. Orai wasn’t so much a village as a handful of sturdy clay homes with latticed windows painted in jewel tones scattered around the walled estate. There wasn’t much more to the small, dust-covered place: two inns that looked like they’d seen better days; a rundown Temple; and a market that was stirring to life just now. A sizable flock roamed on the outskirts, tended by two shepherd girls no older than twelve. The girls’ hair hung down to their waists in thick plaits weighed down with beads and charms. Older women of the village wore their hair wrapped in elaborate whorls of dyed cotton, one of the few signs of finery here.

On every map we’d consulted before crossing the Plain, Orai was the only village noted besides Sellei Lake and Meteen, an outpost for bloodkin nomads who regularly traveled the region. But while Sellei, now a dried-out basin, and the outpost were marked correctly, Orai was not fifty miles west, as every map indicated. It took an extra week of searching, but two days ago, we finally found it. Miles south and hidden behind a rise of stone outcrops still resonant with the scent of earth magick.

I’d briefly fantasized about the wondrous place someone had gone to such lengths to keep hidden. I conjured great marble walls rising around a vast khimaer enclave. But this speck of a village deep in the Plain?

It made sense.

Sense that crawled over my skin, along with the realization that had I looked to find it, had I focused and listened and questioned my father more, I would have known he was keeping a secret. The King of Myre and Lord Commander of the Queen’s Army had come from this forgotten place, and his family never followed him to the capital to bask in the wealth his marriage brought? Of course they were hiding something.

Whoever had looked closer at my father’s life must have ferreted out the truth and killed him.

Sunlight graced the limestone wall of the estate, which rose tall enough to kiss the relentless lapis sky. It dwarfed every other structure in Orai several times over. A simple teakwood door sat in the center of the wall, and the limestone bricks were etched with ancient beasts. A detail I could not make out from so far away, but our first night here, Anali and Falun had ventured close enough to take note of them.

Twin spires, lit like bars of golden sunlight, peeked out behind the wall, the only detail of the estate that was visible.

Even with an eyeglass, this was all I could see from miles away. All I had seen of my father’s family and home, after two days of surveilling the estate and Orai. In those two days, no one had gone in or out. No one from the village approached the estate or so much as glanced its way. I watched the windows high up on the wall for signs of movement, even knowing there was no use.

No figures would come to fill them. My guards had been keeping watch all day and all night. They saw no more than I did. And everyone they questioned in the village either shook their heads and ignored them, or said the house had been silent for a year.

What was the family living inside that wall to this village? How could the Lady of the House lead it without interacting with it? I came here seeking answers about my father and how he’d managed to hide as a khimaer for so long, but I couldn’t deny my hope for a plan. A list of allies and nobles sympathetic to our cause would help. Or even better, a way to persuade the Court and my mother to accept a khimaer Queen, when a lengthy set of laws designed to keep khimaer from amassing any power stood in my way. I’d searched through all my father’s things before leaving Ternain and found nothing.

I hoped Papa’s family would be able to give me those answers. If not, well, I wasn’t sure what I’d do.

“How much longer must we wait?” I asked, slapping the eyeglass shut. Sweat coated my skin, and I shivered as it cooled in the wind.

Anali ignored my question. “You saw exactly what I did. There’s been no movement.”

“How long must we wait?” I said quietly, not bothering to hide my impatience.

Anali’s sooty eyes flitted to mine and held. Her ice-white hair, a sharp contrast to her darkly luminous skin, was braided tight to her scalp. In the weeks since we left Ternain, she’d woven colorful bits of fabric through the braided ends and fine gold chains hung from the ram’s horns that framed her face, dangling violet beads that matched her feathers. Neither was a decoration she would’ve been allowed in the Queen’s Army, though the masculine cut of her clothes was the same. “A week, then we can be sure—”

“In a week, soldiers could arrive. Do you want to remain here long enough to get caught? It was dangerous enough coming here.”

We’d searched for any sign that soldiers from the Queen’s Army had been to Orai. So far, blessedly, there had been none. But that didn’t mean they wouldn’t soon arrive. This village and the family that supposedly dwelled in it were my last tethers to my father. But coming here was a risk I was willing to take.

“And yet, we are here,” Anali said, voice hard. “No need to rush and endanger us further.”

I sat up, tucked the eyeglass within the heavy belt around my waist, and began the climb down the stone. Pain stabbed at my abdomen, and the copper tang of blood filled my mouth as I bit my tongue.

The pain receded and my thoughts became unfocused. I centered my attention on the craggy rocks beneath my palms. An easy calm slipped over my skin as I worked my way down, moving mostly by instinct. I half slid, half bounded down the near-vertical wall of rock.

Soon, too soon, I reached the ground. I flexed my fingers. Thick black claws curled over my fingertips, caked with bits of clay from the climb. I prodded the bandage low on my stomach, hissing through my teeth until I was satisfied the wound hadn’t split and begun bleeding again.

Another luxury I had come to miss: healers at hand.

At the crunch of my Captain’s boots on the rocky dirt, I crossed my arms to hide their trembling. I didn’t want to remind anyone of the injury, least of all Anali. “Maybe I will walk down in the night by myself. I bet I could scale that wall quicker than the rest of you.”

I bet I could slip down there at night without any of you noticing and acquaint myself with whatever lies behind that wall before sunrise.

None could kill me but my sister. On the evening of my nameday, at the start of the celebration, the Sorceryn had placed a complex spell on Isadore and me so that only we would be able to kill each other. Its power would even bar accidents from taking our lives. The only way for either of us to die was by the other’s hand. Now that Isa was my prisoner, I was safe. Safe at the least from death. Better to use me than risk anyone else.

Anali arched a salt-white eyebrow. “So you will force me or the Prince to carry you back to camp.”

I offered her a dry smile, curling a hand in invitation. “Maybe I won’t let you.”

I was stronger now and faster than I’d been. One of the benefits of breaking the block on my magick, I assumed. Not to mention whatever strange power I now had that made climbing the Plain’s craggy hills and buttes as easy as walking or swimming. Well. Perhaps not as simple as walking. But the power coiled in my limbs had grown, and with it, so had my sense of the earth.

Anali’s face softened with mirth. “While the idea that you would easily best Aketo and me together is hilarious and might make for quite a show, it does not sound as though it will get you any closer to your goal. I understand you tire of this delay, Eva.”

“It’s been too long, Anali. We’ve been gone too long and have nothing to show for it.” All we had done since my nameday was run from one village where I couldn’t show my face to another village where the same rule held. Six weeks had passed without news from the capital, but we all knew it could come to an end at any time. My mother would have to reveal what happened, if she hadn’t already, and once she caught my scent, who knew what she’d send after me.

Two more months and Far Winter would be upon us.

Every day the air grew colder and the nights stretched longer until soon even the sun wouldn’t be enough to keep us warm. Cold would roll down from the mountains like a specter, freezing earth that had been baked dry by the High Summer sun. Snow would follow and chase most of the animals who lived on the Arym Plain south across the river until spring.

“I know you’re tired of waiting, but we can’t afford mistakes,” Anali repeated. “If you go into that village and someone recognizes you, word will travel.”

I brushed a hand over the base of my horns, claws clacking against their ridges. The horns grew an inch into my hairline and every nearby curl wound around them in dense tangles. I missed Mirabel’s steady, patient hands braiding my hair. The haphazard twist at the back of my neck was the best I could do.

“Few will recognize me like this.” My voice was soft, so much so that I was surprised when Anali heard it over the wind.

Her eyes hardened. “Even if they don’t know who you are, tales of a horned girl on the Arym Plain will travel. The Arym Plain, where your father’s family has lived for centuries. Whoever else knows about the King will know exactly what that means.”

I couldn’t argue with that, but my mind was not going to be changed. Six weeks and I was no closer to understanding my khimaer magick. No closer to learning who I really am.

Six weeks with Baccha gone. And now two days here, wasted as we waited and watched. “We’ve been lucky all this time. The Queen won’t wait forever to strike. And we’re too exposed. We need shelter. We need baths.” And we needed to consider what would come next.

I needed to consider my future, and Myre’s as well.