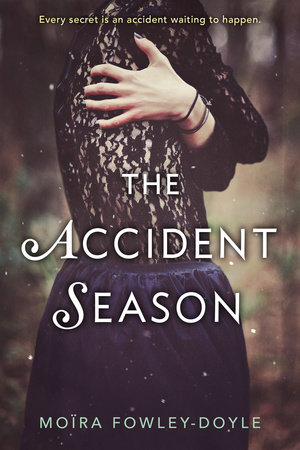

All the Bad Apples

- Pages: 320 Pages

- Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

- Imprint: Kathy Dawson Books

- ISBN: 9780525552758

An Excerpt From

All the Bad Apples

•

After the funeral, our mourning clothes hung out on the line like sleeping bats. It had rained in the cemetery and everything was muddy. Wet grass clung all the way up to our knees and clumps of muck stuck to the heels of our best shoes.

“This will be really embarrassing,” I kept saying to anybody who would listen, “when Mandy shows up at the door in a week or two.”

Rachel gave me a pitying look, but my best friend, Finn, was uncertain.

That’s the problem with having a funeral for your sister without really knowing whether she’s dead. Without a body in the coffin, how can you be sure she won’t come back?

1.

A nice, normal girl

Dublin, 2012

On my seventeenth birthday, two things happened.

I came out to my family (somewhat by accident).

And my sister Mandy disappeared.

Died, Deena, Rachel said—our other sister, the middle sister, the one who came between us. Died, not disappeared.

But I knew Mandy wasn’t dead.

It was raining that morning. I’d woken early, surfacing with a shock from dreams of drowning, of cliff faces with sharp teeth and gaping mouths. Rachel was already up when I came downstairs, frowning at her phone.

The table was set with the best china, the plates we saved for Christmas, and on mine were two strawberry Pop-Tarts—the birthday breakfast I’d loved when I was little. They were still hot; my sister must have heard the shower running, timed it perfectly. She had spread the good tablecloth, red with white polka dots, and had set a bunch of violets, my favorite, in a vase in the center. The birthday card beside my plate was the expensive pop-up kind. Rachel was always trying to make up for my lack of a mother by mimicking some ideal fantasy version.

“This is amazing, Rachel.”

But Rachel was distracted, still reading the text she’d just received.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

“Dad’s on his way,” she said.

“What?”

“He messaged just now to say he’s getting the train. He’ll be here this afternoon.”

“Dad?”

“Yes.” My sister’s mouth was a thin line.

“As in our father?”

“Yes, Deena. Dad as in our father.”

I hovered in the kitchen doorway, watched my sister sigh and tuck a stray red curl—a darker, neater version of mine—behind her ear, rub her forehead with one finger like she was trying to erase the lines there.

“What do you think he wants?”

“Maybe he wants to wish you a happy birthday,” she said with a shrug. “Happy birthday, by the way. Sorry. Should have led with that.”

I couldn’t find the voice to answer. I had a theory as to why our absent father should feel the need to visit this week. I didn’t think it was anything to do with my birthday.

He knows.

My face must have betrayed me. “Is everything okay?” Rachel asked.

I poured myself some tea. “Nothing,” I said. “I mean, yeah, I’m fine. Are you sure Dad didn’t say why he’s coming to Dublin today?”

Rachel sank a mixing bowl into the sudsy sink, wiped at the batter left around the edges. “It’s your birthday,” she said, not quite answering the question.

I gave my sister a come on look. “And when’s the last time he visited for any of our birthdays?”

“I don’t know, Deena.” Rachel sighed. Her impatience was probably more about Dad’s impending arrival than my question. “Maybe he has business in town.”

Or maybe the rumors that had been floating around school recently had somehow gotten back to him and he wanted to come over and confront me about them himself.

Our absent father all but abandoned us—his three mother-less children—when I was less than a year old. He oversaw from afar our education (in the strictest, single-sex Catholic school he could think of); he only called us if he’d heard rumors that we were not upholding the Rys family name; he only ever dropped in on us unannounced, as if to try to catch us out, so determined was he to make sure we were the good, traditional, God-fearing daughters he expected us to be. All the while clearly not caring enough about us to actually stick around.

Which left me with my sisters.

My sisters were fraternal twins. Mandy was older by twenty-four hours, although she neither looked like the eldest nor acted like it. Rachel had always been impossibly adult—practical and mature—and was now positively ancient at thirty-four. But while Rachel raised me, did her best to tame me, Mandy wilded me, carelessly undoing all of Rachel’s work: muddying my shoes, tangling my hair, making me question authority.

Mandy and Rachel were night and day, fire and frost, chaos and logic. They were opposites in so many ways, their few similarities were shocking.

They were my family, these sisters, this strange push and pull.

Our father had long since given up on Mandy, and I knew exactly how he would react if he ever found out about me.

Sitting across from me, Rachel narrowed her eyes. “What is it?” she said.

I attempted a breezy tone. “Nothing really,” I said. “It’s just there’ve been some rumors going around school. For the last week or so. About me. I’m a bit worried they might have come back to Dad. Through one of his friends on the school board or the parents’ association. You know.”

“What kind of rumors?”

“All kinds. You know my school.” I wrapped my fingers around my teacup, made the decision to say it almost before I realized the words were coming. Deep breath, dive in. “But mostly there are rumors that I’m. Um. Gay.”

Rachel squared her shoulders. “Our father would know better than to believe a rumor like that.”

I never understood why nerves were described as butterflies in your stomach. This was more like a prolonged electric shock.

“They’re true,” I said softly. “The rumors. I’m gay, Rachel.”

My body could have set off sparks. Rachel opened her mouth to speak.

It was at that perfectly unfortunate moment that our father walked unexpectedly into the kitchen. Panic rooted me to the spot. I could have been felled by a single ax stroke, falling with limbs askew like branches.

For half a second, I thought he hadn’t heard me, but all the wishful thinking in the world couldn’t change the way his face—neutral, lined, neat red hair gone mostly gray—had twisted in fury.

When he spoke, his voice was low and dangerous. “What,” he said, “did you say?”

My voice froze in my throat.

“Nothing,” I whispered, the word sounding strangled and strange. I could feel the color leach from my face.

“Dad!” Rachel jumped up from her seat. “You’re early! I thought you’d still be on the train.”

Our father ignored her. “What do you mean, nothing?” he said to me. “Nothing what?”

“Deena was just saying,” Rachel said in Dad’s direction, fast and nervous, “that sometimes girls say the most horrible things. That’s bullying, you know. I’m sure it’s against school policy.”

“Don’t you go covering for your sisters again,” Dad shot back at her. “That school’s feckin’ policy is the reason I’m here in the first place. Getting people in to talk about deviant lifestyles with impressionable kids.” He gestured at me, grimacing. “It encourages this kind of disgusting talk.”

“I’m not—” I said. “I didn’t mean—”

Dad’s voice lowered, had that dangerous edge to it again. “You’re damn right you didn’t mean,” he said. “And you’ll say nothing like that ever again, you hear? I’m giving you one last chance. If I get even a whiff of this off you again, I’m sending you to one of those camps. Sort this nonsense out once and for all. I won’t have another bad apple in this family. Mandy’s bad enough already. No daughter of mine—”

“Dad,” Rachel said peaceably. “This is all just a big misunderstanding. Everyone knows Deena is a nice, normal girl.”

“Then she’d best start acting like it,” Dad said to Rachel as if I weren’t in the room, as though I were a naughty child needing to be taught some manners.

I could neither speak nor stop the tears that had sprung up the moment my sister—the one whose opinion actually mattered to me—had said the words nice, normal girl.

I wanted to speak up, defend myself, tell the truth. Instead, I did the only thing my body seemed capable of doing, something that probably proclaimed my guilt even more than my tears. I turned and ran out the door.

2.

Please stand for morning prayers

Dublin, 2012

The words drummed on my umbrella like raindrops. Nice, normal girl fogged up the air in the crowded bus. Nice, normal girl formed puddles on the school grounds that my shoes threatened to slip in. Nice, normal girl.

I walked into the hall for Friday assembly, drenched despite my umbrella, shivering. I draped my dripping coat over the back of my chair and took two long puffs on my inhaler. They didn’t help unknot the panic in my chest.

The hall filled slowly. Girls in green sweaters and tartan skirts sat in small clusters: the prefects and class reps to the front, the rebels at the back, the popular girls in the exact midpoint of the hall—the center of our small universe. The rest of us branched out from them, groups of friends chatting together or yawning, scrolling on their phones or showing off their renegade nail polish, strictly forbidden by the school dress code.

I sat alone.

My phone lit up with a message from Finn.

Many happy returns on this the day of your birthday which I wish I was spending with you instead of in math test purgatory. Pretty sure Mr. Geary is going to fail me. Approx. 5 hours of homework dished out already and it’s not even 9. Me and some of the lads are considering an uprising. How’s your stats looking?

My best friend, by virtue of being a boy, was unable to attend the same school as me, which would have made the long hours I spent there infinitely easier. As it was, we had to be content with narrating the tedium of our weekdays via text. Finn was smart, and well liked in his school, so his tedium mostly consisted of being overworked by admiring teachers who only wanted the best for him.

Bleak. Stats as follows. Dirty looks received: two. Whispers directed at me: three. Possibility of nasty rumors circulating: mid to high.

I didn’t mention anything about my dad.

Stay strong, Finn messaged, his usual parting words.

I got in a You too before the vice principal called for us to please stand for morning prayers.

I could recite the Our Father in my sleep, so I let my voice go to autopilot and looked around at the other girls, noticing that two seniors a few rows behind me stayed seated, kept their mouths clamped shut during morning prayers in silent protest.

They were stone warriors, chins raised defiantly like statues of queens. One had long earrings, two bright purple plastic Venus symbols. The other wore two pins on her collar: one was a large enamel rainbow flag. The other said don’t hate, educate.

Nobody gave these girls dirty looks. No rumors circulated about them the way they did about me. They were untouchable; they radiated cool. Unlike me—ill-defined and self-conscious, plump, freckled, and bespectacled like the bumbling best friend in an old children’s book—these girls announced themselves, chins high, daring anybody to challenge them. We may have sheltered underneath the same umbrella, but, in the many judging eyes of the school, we were completely different species.

Our prayers ended to a chorus of amens.

“All right, girls.” The vice principal’s voice came through the mic in front of her. “As you all know, there has been some hullabaloo about the cancellation of the Schools Out Loud workshop last week.”

It had been all over local news and radio:

Dublin school calls off LGBT youth group’s anti-bullying workshop.

Sixth-year girls organize protest against school’s cancellation of LGBT group lecture.

Those seniors, soon joined by a couple of the more confident younger girls, had been quick to criticize the school’s decision. When I’d tried to do the same during lunch break on Monday, my classmates’ eyebrows had immediately shot up.

“You have probably seen our statements on school social media,” the vice principal went on. “Our Lady the Mother of Immaculate Grace Secondary School has a zero-tolerance bullying policy. We are proud to have a diverse student body. However, some parents expressed concern over an activist group speaking without a fair and balanced counterargument present. The school board is looking into speakers who can represent the other side of the discussion. In the meantime, the Schools Out Loud workshop has been postponed, not canceled.”

I chanced a glance behind me. One of the two sixth-year girls had bent her head to whisper in the other’s ear. They both rolled their eyes, then glared back at the stage, sitting even straighter. A girl in my class, sitting close by, noticed me looking and elbowed her friend. They both giggled.

There had always been rumors about me, but this week in particular they’d gotten a lot louder. And my father now knew they were true.

Face flaming, heart pounding, I turned to the vice principal again.

“I would also like to remind students of our school dress code,” she was saying. “No pins, badges, or garish accessories will be allowed during school hours and on school uniforms. As always, Our Lady girls are expected to be well groomed, well presented, and uphold the reputation of our school. Slán agus beannachtai Dé oraibh.”

Goodbye and God’s blessings be on you. Provided you aren’t wearing a rainbow pin.

The two seniors stood at either side of the assembly hall doors as the school trickled out, proud sentinels handing out printed leaflets calling for a student protest.

I hung back. One of them beckoned me over. Her earrings had just been confiscated and she kept reaching up with her free hand, feeling their absence.

“You joining the protest?” she asked. I wondered if she could sense it on me. “The details are on the event page.” She pointed to a link printed on the flyer.

I couldn’t join the protest. It would be like painting a big rainbow target on my back. Still, I felt my cowardice like a toothache, sharp and constant.

“I’m sorry your earrings got confiscated,” I said to the girl instead. “They were awesome. It’s completely unfair.”

The girl looked surprised for a moment, then smiled, as if she was pleased I had noticed. “Thanks,” she said. “I made them myself.”

“What? Really? They’re amazing.”

She pushed the flyer into my hand and I took it automatically, grinning stupidly.

“Monday morning,” she said. “Scheduled walkout. See you there.”

She turned to wave her leaflets at a group of sophomores behind me and I carried my flyer and my smile halfway down the corridor, thinking that maybe things could be okay, that maybe I could even talk to pretty older girls who made their own earrings, that maybe if I joined the protest nobody would suspect a thing.

Until I slowed by the bathroom and overheard four girls from my class talking about me in front of their lockers.

“Oh my God,” one of them was saying. “Did you see Deena Rys drooling over that senior? Scarlet for her.”

A flurry of whispers erupted in the wake of her words. I shoved through the door toward the bathroom, to splash cold water on my burning face.

When the door closed behind me, I thought I could hear one of them saying, “Okay, you win. I’m changing my vote.”

I didn’t wonder long what vote she meant. When I walked into French, before the teacher but after most of the other girls, it was right there on the whiteboard at the front of the class.

It said, in glaring bold black letters:

IS DEENA RYS A LESBIAN?

Underneath the words were three columns. The first said Yes. The second said No. The third said, in somewhat squashed writing, She’s too ugly to get a boy so she may as well try dykes.

In the first column there were ten votes. In the second there were three. In the third there were twelve.

It was every nightmare I’d never even thought to have, and I was so mortified I didn’t even feel it. I stared at the board for a long moment, loaded silence coming from the desks behind me.

I could have said something. I could have gone to the vice principal with her “zero-tolerance bullying policy.” Instead, I walked out of the classroom and nobody stopped me. Tears trailed hot and shameful down my cheeks, but still I slammed the door so hard the crucifix above it fell off the wall and crashed to the floor.

3.

The Rys family curse

Dublin, 2012

Without it being a conscious decision, I walked all the way to Mandy’s, crying, in the rain, my umbrella forgotten under an assembly hall chair.

Mandy had never lived with Rachel and me—not since a little after I came along anyway. I, the afterthought, the accident, the small slip of the tongue, born seventeen whole years after my sisters, the final straw that killed our mother. At around the same time that our father left, Mandy and Rachel fell out, loudly and dramatically—at our mother’s funeral, no less, or so the family always said. Mandy had left Dublin, to who knows where and doing who knows what, but she came back after I’d started school. Since then, she’d lived in a dingy flat in Fairview with two friends and a revolving cast of couch-surfers with varying degrees of personal hygiene. As far as I was aware, she’d given back her key to the family home. Whenever I asked what they had fought about so seriously, my sisters were uncharacteristically united in their silence. But there was nobody else to ask; the rest of our family had had very little to do with us since that very fight.

Mandy had quit school at sixteen, told me she’d learned everything she knew from the Marino public library. She had once been fired from a job in a bar because she had punched a man who’d groped her. She’d had a scandalous affair with a married banker, spent two weeks in his penthouse apartment in Marbella. She’d toured with a punk band for a few months in her teens. She’d joined a cult, briefly, in her twenties, had lived off the land with other white-clad, barefoot women, until she grew weary of their rules, said they were just as bad as the church she’d left as a girl.

She’d let me smoke a joint with her last year, laughed when I told her that her gray eyes were exact mirrors of mine, fed me chocolate cookies until I fell asleep. She snuck me into concerts and burlesque shows, convincing the bartenders I was over eighteen, slid sugary cocktails across the table to me. She let me borrow books that Rachel would undoubtedly have considered unsuitable, which I read curled up wherever I could find a clear bit of space in her bedroom, sipping coffee, listening to the rain.

I had never come out to Mandy, but I had long suspected I didn’t have to.

“Our family tree blew down in a gale and we are the bad apples it shook off,” Mandy said, the moment she opened the door of her flat.

“What?”

“Bad apples,” Mandy repeated. “Isn’t that what Dad always says?”

I stood openmouthed and dripping in the hallway, unable to tell my sister that Dad had used those exact words that very morning, that her saying this, specifically, right at that moment, was eerie.

“Bad apples don’t have history,” she went on, handing me a towel. “They don’t have roots. They just sit in the grass where they fell, rotting alone.”

Or they walk all the way to Fairview in the pissing rain without an umbrella to knock at their sister’s door.

“Speak for yourself” was all I could say, but I knew she already was. Mandy was the baddest apple in our bunch, and I loved her for it.

Drying my hair, I followed my sister through the dusty, dimly lit flat into her bedroom. The floor was covered in notebooks and folders and library books about nineteenth-century landed gentry. She flopped cross-legged onto her unmade bed and gestured at her cluttered bedside table, upon which was a fresh mug of coffee, perched next to a pink-frosted cupcake topped with a flickering candle.

“Happy birthday,” she said, cigarette-scratchy. “I hear Dad’s in town. Have my coffee—you look like you need it.”

“Thanks,” I said, warming my palms on the full mug, still thinking about her saying we were bad apples. “So Rachel called you? What did she say?”

Mandy threw an arm over her eyes. Her hair, the signature Rys red, more auburn than my orange, fell in messy curls halfway down her back, several strands, once bleached and dyed purple, now faded to a dusty lavender, red at the roots. There were shadows of sleepless nights under her eyes. “Not much over the phone. She says she wants to see me later, to ‘have a chat,’” she said. “I need a drink.”

“You’re not the only one,” I muttered.

My sisters had very different reactions to meetings with our father, but both seemed to come from the same place. Rachel’s mouth would tighten so much her lips disappeared, and by evening the house would be spotless, sparkling, and her hands rubbed raw from scrubbing traces of dirt from the bathroom walls. Mandy’s mouth would only tighten when it was round a bottle and she’d be messy drunk by evening. If the interaction was particularly bad, she might disappear for a few days.

“Did Rachel say what she wants to talk about?” My heart beat in my throat.

“No, but don’t worry about it.” She pushed the cupcake across the bedside table. “Make a wish.”

My stomach tightened. I made a wish and blew out the flame.

“Do you feel different?” my sister asked me.

“What? Because of the wish?”

Mandy barked a laugh. “If you like,” she said. “But I meant now that you’re seventeen.”

Seventeen was hardly the age of spindles and spinning wheels, but to Mandy it seemed to still mean something. I wanted to lie, tell her I felt no different than I had the day before, assure her that there was nothing unusual about this day, no pivotal moment that had sent me running to her. I was suddenly unsure I could tell even her, could risk saying the words again.

“A bit, yeah,” I said.

“Your present’s on the floor beside you,” my sister said.

I pulled a heavy box wrapped in newspaper and kitchen twine onto my lap. When I opened it, it was filled with books.

“Mandy! Thank you!”

“Have a look,” she said.

I took the books out one by one, stacked them on Mandy’s overflowing little desk with her library books and refill pads and folders full of who knew what. After I’d taken the third book out, I understood my sister’s present.

These were more than just the kind of books I couldn’t find in my school library. Than those I’d read, illicitly, at Mandy’s since I was little. These were books I would never have had the courage to let anybody but Finn see me read.

There were silhouettes of girls holding hands on a couple of the covers, and on one—a shiny, hardback American edition—two girls kissing. I shook my head at the audacity of my sister, at my own embarrassment, at the sheer perfection of both her timing and her gift. From Tipping the Velvet to Cameron Post, an entire library of girls like me.

“You can keep them here if you like,” she told me. “If it’s easier.”

I didn’t want to put the books back in their box.

Mandy was watching me carefully. “Was I wrong?” she asked gently.

I felt strange, nervous, choked up, tearful. “No,” I croaked. “You’re not wrong.”

“I have another present for you,” she said, brushing aside my garbled thanks. “But it isn’t ready yet.”

“This present is perfect,” I said, voice shaky, still overwhelmed. “You don’t have to get me something else.”

“I want to,” said Mandy. “It’s just not quite finished.”

“That’s okay. It can be a surprise.”

“I’m shit at surprises,” said Mandy. “So I’ll tell you. I thought we could take a little vacation, just the two of us. A road trip. What do you reckon?”

On my tenth birthday, Mandy had picked me up from school unexpectedly. We drove to the westernmost part of Donegal with a tent, two sleeping bags, a backpack full of books, enough candles to light a small church, and the horned skull of a bull. (Even at ten, I was aware that Mandy was a little eccentric.) We set up our tent in a campsite on the dunes facing the ocean and we spent our days reading on the windy beach, talking to the cows in nearby fields, and going for long walks upon which Mandy always seemed to be looking for something. We were constantly covered in sand and salt that scratched when we slept, we’d forgotten to bring a brush, so our hair was all tangles, we washed our underwear by hand in the sink of the camping-ground bathroom—and I’d never had so much fun in my life.

At night we’d howl at the waves and when we got tired Mandy would wrap us up in blankets with a thermos of tea and tell stories about Tír na nÓg, the fairy land far west across the water—to which the poet Oisín was carried on the back of a white horse in the myth everybody knew—where nobody gets old or sick and no one ever dies.

On the last night she drew a large circle on the sand with salt from a shaker she’d stolen from the local pub. She sat me in the middle with the bull skull and the candles, which didn’t blow out even in the strong sea breeze.

“He’ll protect you,” Mandy told me. “Keep you safe.”

But I always felt safe with Mandy anyway.

It was only when we returned to Dublin a week later, barefoot and dirty, bright-eyed, windswept, and tangle-haired, that I learned Mandy hadn’t told anyone else she was taking me on our camping trip.

After several days without a word from Mandy, Rachel had called our father. At the time I thought Rachel had overreacted, had betrayed us by involving him, but, now that I’ve thought about it, she must have been so worried. That she hadn’t called the police meant she’d trusted Mandy that much at least.

When we returned, there was all manner of uproar. Dad called constantly for the next few days with criticism and unsolicited advice. I sat on the stairs in the hall and listened to Mandy and Rachel argue, listened to Mandy shouting at our father on the phone before storming out, then listened to the phone ring and ring unanswered when his number kept coming up.

I’d snapped and snarled and told Dad those seven days had been the best in my life, and he told Rachel, “She’ll turn out just like her if you don’t do something.”

“What is it?” Mandy’s eyes now searched my face like spotlights, illuminating all the hidden corners. She’d started doing that. For weeks, I’d catch her watching me, as if she was waiting for something. As if I would break out in blisters, spontaneously combust, disappear.

“Nothing,” I said, my traitor cheeks flushing the same pink as my cupcake. “A road trip sounds brilliant. Where will we stop along the way?”

“That’s why it isn’t ready yet. I’m still working out the route.”

I smudged a finger into the icing, licked it. “It’s a great birthday present,” I told my sister. “Thank you. And for the books.”

“I’m glad you like them.”

I puffed out my cheeks and said, “Your timing is kind of spooky, actually, because I kind of accidentally came out to Rachel this morning.”

Mandy’s face went through several expressions that I couldn’t read before settling on a sort of resignation. “Don’t worry, Deena,” she said. “Whatever she said, Rachel will come round eventually.”

“Mandy, Rachel didn’t—”

“She’s just still trying hard to hold on to her plan for you, but she’ll understand it’s changed soon enough.”

“Her plan?” I repeated.

“You know,” Mandy said. “She likes to think of you as the perfect blank slate for everything she never got to be. A wife and mother with a worthwhile career. She’s probably planned your and Finn’s wedding and picked out your babies’ names already. She just wants you to get the life she couldn’t. As a nice, normal girl.” Mandy made air quotes; these were Rachel’s words, not hers. A lump formed in my throat at hearing, for the second time today, the very phrase I couldn’t get out of my head.

Mandy brushed her hair behind her shoulders with one sweep of her arm and said, rather grudgingly, “It’s because she loves you, you know.”

“I know she does. It’s just I am a nice, normal girl, you know?”

Mandy laughed. “If you say so, kid.”

“I do.” I stroked the spines of the books. “Although—I’m not sure Dad does anymore.”

Mandy stared at me. “What do you mean?”

The fury on my father’s face flashed into my mind. “He heard me,” I said, the words heavy. “He came into the kitchen as I was telling Rachel.”

She sat up abruptly. “He what? Are you sure?”

Our father’s words echoed round my skull. Deviant lifestyles. Disgusting. No daughter of mine.

“Oh yeah,” I said. “I’m sure.”

Suddenly Mandy’s face was stricken. “No. No. No, no, no. Deena, you can’t tell anyone else. Nobody else can find out.”

“What?”

She clutched her head, shook it, her hair tangling in her fingers. “If it were just me and Rachel . . . but if Dad knows—” Mandy took a breath. “Do you remember when we went up to Donegal for your tenth birthday?” she asked.

“Of course. Our infamous road trip. I was just thinking about that a few minutes ago, actually.”

Mandy sat forward, hands on her knees, bracing. “Do you remember what I told you on the last night?”

Sand and salt, fire and bone.

“No?” The word was a question. I remembered the bull skull. I remembered her telling me the bull would protect me, keep me safe. I remembered feeling enchanted, but mystified.

“Do you remember what I told you about our family?”

“Not really. Sorry.” But a memory was dredging itself from my unconscious, ringed in salt. “Yes,” I said. “Sort of. Did you tell me some kind of story about a family curse?”

Mandy nodded deep. “The Rys family curse.”

We knew next to nothing about the Rys side of the family because Dad never talked about them. When we spoke about our family, my sisters and I, we meant the MacLachlans, our mother’s kin. We rarely saw them—each as self-righteous, pious, and judgmental as the last. They’d taken Dad in with approving, welcoming arms.

I shrugged, bemused. “The Rys family curse. Remind me.”

“Bad things happen to the bad apples in our family,” Mandy said, her eyes unfocused, her voice trance-like. Small pinpoints of unease prickled along my skin.

“You were saying something about bad apples when I first got here, right? What was it again?”

“You know the kind,” she went on as if I hadn’t spoken. “You’d know them a mile away. The ones who don’t look like the others, don’t act like the others. The ones who don’t conform, don’t follow the rules, don’t go to church on Sunday. The ones who run away, make their own lives. The ones who drink too much, talk too much, don’t work enough or at the right things. The ones who dress differently, love differently, think differently. Our family tree protects its good seeds, keeps them safe. But the bad apples get shown the door. Shunned, ignored, talked about in hushed whispers. They get pushed off the tree, breaking every branch on their way down. And once they’ve fallen, once they’ve been cast off the family tree, that’s when the curse comes to them.”

“The curse.”

“It happens at the age of seventeen. Like some kind of fairy tale. If you’ve lived a life on the straight and narrow, the curse may never find you. But, if you’re considered rotten by the rest of the family, you’re doomed.”

I stared at her. “Doomed? What does that mean exactly?”

Mandy stared right back. “It means deaths and disappearances. Terrible losses and tragedies. Things you’ll carry with you always.”

“But, Mandy—”

“I’m telling you, Deena, if the family thinks you’re rotten, you’re doomed.”

The rain battered at her bedroom window.

“You’ll know for sure if you hear the banshee scream.”

The icing of my birthday cupcake was pastel paste on my fingers, sticky and too sweet. “The banshee,” I repeated. “This is a metaphor, right?”

“It’s not a metaphor. There are three of them. The first is the one whose screams mark you as cursed. Then you’ll find gray hairs fallen from the second’s bone comb tangled on the threshold of your home. You’ll know there’s no hope left when the third scores your skin with her sharp nails as you sleep.”

I placed my half-eaten cupcake back on Mandy’s bedside table. This was not how I’d expected this chat to go. Mandy believed in many things—ghosts, UFOs, conspiracy theories. It made sense that she would believe in banshees, in family curses. But what she was telling me now I didn’t understand. I didn’t want to understand.

“I’m afraid,” said Mandy. “I’m afraid this is the curse. I’m afraid you’re another bad apple ready to fall from the tree.”

My heart was hit with hammers. “I’m not a bad apple,” I whispered. “This doesn’t make me a bad apple.”

Mandy stared right through me. I wanted her to say Of course not. I wanted her to say I know that.

“You’re cursed,” she whispered. “This has to be the curse.”

“Mandy, I’m gay, not cursed. I didn’t know Dad was home yet. I didn’t know he would hear me. I would never have said anything if—”

Mandy was speaking too fast and too loud. “I didn’t think it could happen to you. I’ve made a huge mistake. If Dad heard you—You can’t tell anyone else. Nobody can find out. Maybe if you keep your head down this year, maybe if you just pretend—”

“Pretend?” The books on the desk mocked me, unboxed, covers loud.

“It’s going to be okay,” she said. “Don’t worry. I can fix this.”

I stood and went with heavy feet to her bedroom door. I could have sunk all the way to the ground floor. “I don’t need fixing,” I said to my sister, but she just let me walk away.

Finn found me later, down by the beach past the wooden bridge. The rain had stopped and the world was wrung out and blanketed in puddles. I was sitting on my jacket underneath the statue at the end of the walk down to Dollymount Strand: a seventy-foot-high Virgin Mary towering over the bay. Our Lady, Star of the Sea. I was on my third coffee (which wasn’t helping the pace of my heartbeat), the paper cups stacked neatly on the ground beside me, and I was scrolling on my phone, dangling my legs above the water.

Finn dropped down to the ground beside me.

“How long have you been here?” he asked.

“Since half past twelve.”

A ferry rolled slowly out of the port at East Wall, and Finn and I watched it—this colossal monster of a thing—sending waves washing toward the strip of land we sat on, under the feet of the Virgin Mary.

“Are you going to tell me what happened?” he asked.

I put down my phone and kicked out my legs. Softly, I sang, “Happy birthday to me, happy birthday to me.”

“Deena.”

“Happy birthday, dear Deena, happy birthday to me.”

“You cut class, for the first time in your life,” Finn said. “You go dark online for the whole day until you ask me to meet you here. You’re acting weird. Er.”

“Very ha.”

“So either you’re deciding to try out a bit of good old-fashioned teenage rebellion on your seventeenth birthday, in which case I applaud you and wish you only the best, or . . .” Finn paused for breath. “Or something happened today.”

The ferry picked up speed.

“So far,” I said slowly, “I think it’s safe to say that this has been the worst birthday in the history of birthdays.”

“Did something happen in school?”

“I can’t go back there,” I told him. “Ever, probably.”

Finn turned to look at me, his features blurry in my peripheral vision. I stared in silence through my glasses at the sea.

“Okay.” He rubbed his hand twice over his close-cropped black hair. “So what’s the plan?” he asked. “You go on the run? Get Rachel to home-school you? Good luck with that.”

Three tears ran silently down my cheeks before I could stop them. “I might not be able to go home either.”

“Shit,” said Finn. “Come on, Deena. What happened?”

“They had a vote at school.” Of everything that had happened so far, this was the easiest to open with.

“What? Who had a vote? Is this about the talk they’re protesting?”

“No,” I said. “No. They had a vote about me.”

Finn shook his head. “You’re going to have to fill in the gaps for me here, Rys.”

I filled in the gaps. I started with school. I began to cry when I told him about my dad. By the time I’d gotten to Mandy’s reaction I was having trouble breathing. Finn put a careful arm round my shoulders. There were certain things that only my best friend could understand, being bi himself. He may not have completely understood why I was so terrified of my father finding out, seeing as how Dad didn’t even live with us, but Finn did understand not wanting to be out loudly and publicly at school. Only a small handful of his friends in class knew. Until this morning, I hadn’t been out to anybody but Finn.

When I had finished, he stood abruptly and said, “That’s it, I’m buying you a chocolate muffin. And when you’ve eaten it we’re going to get my cousin to buy us some cider. Screw those bitches in school. And screw your whole damn family. It’s your birthday. Tonight we’re going to get drunk and talk about girls.”

He strode purposefully back to the little coffee shop by the car park, his hips lean in his gray uniform trousers, his head high. I understood why Rachel had always wanted me to end up with Finn (apart from the obvious fact that he was the only boy who’d ever shown interest in me, romantically or otherwise). Life would be so much simpler if I could just fall in love with my best friend.

Above me, Our Lady, Star of the Sea watched the ferry slide slowly out of sight. When I turned back around, ahead of me in the water there was a woman.

Not a swimmer. Not somebody who’d jumped into the bay on a dare. An old woman so pale her skin seemed gray, submerged past her mouth, her long silver hair tangling through the foam of the small waves around her. A woman with a ravaged, skeletal face, cheeks sunken, eyes set deep in wrinkles, their irises as gray as her hair.

She wasn’t treading water. She wasn’t moving at all. She was staring right at me, unblinking.

A long gray hand came out of the water. Its twisted fingers beckoned.

I couldn’t explain what happened next, only that I must have started so hard I slipped off the rocks at the base of the statue and into the water. There was nobody close enough to push me. The woman was too far from me to have pulled.

A split second and I went under. Not even enough time to feel real fear. Water whooshed around me, filled my ears with roaring and my mouth with salt. I kicked wildly toward the surface.

When I came up, the woman’s face was a hair’s breadth from mine. She opened her mouth and screamed.