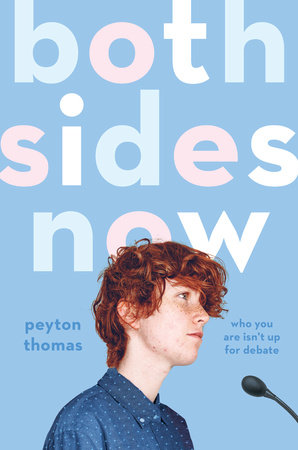

Both Sides Now

Ebook

$9.99

- Pages: 304 Pages

- Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

- Imprint: Dial Books

- ISBN: 9780593322833

An Excerpt From

Both Sides Now

chapter one

“Sorry—we’re the Soviets? You and me?”

“Come on, Finch: When have I ever steered you wrong?”

He’s got a point. In all our years of debating together, Jonah Cabrera has only steered me right. In my bedroom, back home, there’s a bookshelf that groans and sighs and threatens to split under four years of blue ribbons and gold medals. It’s an inanimate testament, that shelf: Listen to Jonah, and you, Finch Kelly, will go far.

Still, I’m skeptical. “You want us to role-play as Stalin’s cronies?”

“Oh, no. Not his cronies.” Jonah swivels to the blackboard, scrawling his points in white chalk. “It’s 1955. Stalin is six feet under. The Cold War’s getting colder. Eisenhower just rolled out the New Look.”

I watch him, hunched over my desk and chewing hard on a yellow No. 2. “Remind me what the New Look was?”

“More nukes, more cove-ops,” he says, standing tall, sounding sure of himself, “and way more American propaganda getting piped past the Iron Curtain.”

“Got it.” I pull the pencil—now a beaverish twig—out of my mouth and take some notes. I won’t lie: He’s selling me. “Keep talking.”

In ten minutes, the two of us will stride out of this classroom and onto the Annable School’s Broadway-sized stage. We will stand before hundreds of spectators, and we will argue, in speeches lasting not more than eight minutes, that every nation on Earth—no matter how rich, poor, or prone to the incubation of terror cells—deserves endless nuclear weaponry.

Do we actually believe this? God, no. Least of all Jonah, the clipboard-toting, signature-gathering student-activist bane of our local power station’s nuclear existence. Among the many buttons presently dotting his backpack, I can see a little one, the color of sunshine, reading: NUCLEAR POWER? NO THANKS! But still, he stands before the chalkboard, doing his utmost to build the case for Armageddon.

“Both teams—the U.S., the U.S.S.R.—they’re fully ready to plant mushrooms all over the map,” says Jonah, with a grand sweep of his arm across the chalkboard. “And the only reason they’re not raining burning hell all over the planet . . .”

“. . . is mutually assured destruction.” I glance at my stopwatch: eight minutes left, scrolling faster than I’d like. “This idea that the only defense against nuclear weapons . . .”

“. . . is more nuclear weapons,” Jonah says. “Because why hit the Russkies when you know they’ll hit you right back?”

As he says this to me, Jonah scribbles a series of suggestive illustrations on the blackboard: smoke, flames, innocent civilians disintegrating into radioactive ash.

If the whole Greenpeace thing falls through, he might have a future as an artist.

Of course, if either of us wants any kind of future at all, we’ll have to go to college first. And if we best the Annable School in the final round of this tournament, the North American Debate Association of Washington State will award us an enormous, gleaming trophy—one that would look great on college applications and, more urgently, on scholarship applications. Jonah’s mom is a registered nurse. My dad’s on his sixth month of unemployment and his seventh step of Alcoholics Anonymous. Neither of us can afford to shake sticks at this particular hunk of golden plastic.

“Okay, but, Jonah, Annable knows exactly how to refute that case.”

“Not if we run the case in the 1950s,” Jonah pleads. He’s literally a blue-ribbon pleader; he is very convincing. “Come on, Finch. Time travel? Ari is never going to see this coming.”

He’s talking about Ariadne Schechter: the Annable School’s prodigy of a debate captain, my worst enemy, my arch--nemesis, the freshwater to my salt. I despise her. I truly do. For so many reasons. Her noxious lavender vape fumes. Her unironic love for one milk-snatching Maggie Thatcher. And, not least of all, her early admission to Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service. I settled for a purgatorial deferral letter. I’m still upset about it.

I think I’d be less upset, mind you, if Ari’s dad hadn’t donated forty million dollars to erect the Schechter School of Sustainable Entrepreneurship on a high cliff at the edge of campus.

But I can’t fall into that swirling vortex of a grudge just now. Not unless I want to lose this round, and this state title, and fall even further out of Georgetown’s good graces.

“This ‘pretend to be commies’ angle is definitely . . . creative.” I’ll give him that. It may be the only thing I give him. “I’m just worried it’s too creative. Rule-breakingly creative. The kind of creative that’ll send Ari whining to the judges.”

“Okay, point one: You’re never not worried,” Jonah says, perching now on the teacher’s broad war-chest of a desk. He gets like this when he’s antsy—pacing, snapping his fingers, sitting on anything but, God forbid, a chair. “And point B: You know we need to spice it up this round. End of the day. End of the weekend. Everyone’s five seconds from falling asleep.”

“You included, apparently,” I say. “You just said ‘point one’ and ‘point B.’”

“Did I? Damn.” He flashes me a sheepish grin, and then a yawn, his arms flying high above his head. “Guess we need to get creative, then. Wake ourselves up”

“By arguing the whole round in Russian accents?”

“Who said anything about accents?” he says, all innocent.

“I saw you in The Seagull last semester, Jonah. I know you’re dying to flex your dialect work.”

“But . . .”

“Not the time,” I tell him. “Not the place.”

“Fine. No accents. Serious business only.” Jonah, still fidgeting, drums his knuckles against the top of the teacher’s desk: sturdy antique oak, the furthest possible cry from the particleboard and plastic of our own Johnson Tech, ninety minutes away on the outskirts of Olympia. “If we go with the standard case here—like, define ‘this House’ as NATO, or whatever—we basically have to argue that more nukes are a good thing.”

“Right. Hard case for anyone to make. Especially you, tree-hugger.”

“But if we set the debate in the Cold War? Cast ourselves as the Soviets? Make Annable argue for the U.S. of A.?” Rocking to and fro on the desk, he disrupts a decorative apple—World’s Best Teacher, etched in the glass. It teeters. I hold my breath. “We don’t have to hash out all the boring, entry-level arguments,” he says. “We don’t have to touch M.A.D. We can run a more historical case. Talk about communism.”

The apple steadies itself. I exhale.

“And capitalism,” I say, and sit up straight, and snap my fingers. “And the Truman Doctrine, and HST, and . . . oh, oh! If we can link that last one to de-Stalinization, we could even . . .”

His hand finds my wrist, halting my Ticonderoga.

“Knew I’d get you on board.” He winks. “Comrade.”

I’ve never met a president, but when I step out onto that stage, I can imagine, just for a moment, how it feels to be one. I am five feet and five unremarkable inches tall, with a thatch of disobedient red hair that falls somewhere between Chuckie Finster and just plain Chucky. I don’t get to feel like a president all that much.

But here, beneath the tremendous light-rig of the Annable auditorium, staring into the ocean of the audience and soaking in their applause, I feel like I could do . . . I don’t know, anything. Deliver the best speech of my life. Cinch the state title. Win a spot at the school of my dreams. Maybe, one day, I could become the first trans person in Congress. None of it—nothing—seems impossible.

I take my seat next to Jonah at the desk reserved for the people arguing yes, nukes, more of them. To our left, at a desk of her own, Ari Schechter is squinting through the bangs of her Hillary Rodham haircut, scribbling a final few words onto her cue cards. She’s paying zero attention to Annable’s principal—apologies, headmaster—who’s standing at the podium, delivering his opening remarks in a throaty Masterpiece Theatre accent. He’s saying things like “free inquiry,” and “open dialogue,” and “the dissemination of diverse perspectives,” and I’m wondering how “diverse,” exactly, the “perspectives” can be, at a prep school that costs $25,000 a year.

“Representing the proposition, from the Johnson Technical High School,” says the headmaster—and it’s very funny, that snooty extraneous “the”; it makes us sound like we belong in a very different tax bracket: “Jonah Cabrera and Kelly Finch.”

I cup a hand around my mouth. “Finch Kelly!”

I’m very proud of my name. I gave it to myself, after all. It’s a good one. But it never fails to trip people up. “Like Atticus,” I always tell them. “From To Kill a Mockingbird,” and then, usually, they get it, and they nod. “Atticus” was my first choice, for what it’s worth, but my parents vetoed it. They were mostly fine with their daughter becoming their son. Less fine with their son strolling around under the bizarre appellation of a second-century Greek philosopher.

“Ah, yes.” The headmaster pushes his glasses up his nose, peers once more at the paper on the podium. “Finch Kelly. My apologies.”

Light applause. A lone, shrill whistle. That’s Adwoa, most likely—our coach, rooting for us from the cheap seats.

“And, of course, representing the opposition: Annable’s very own Ariadne Schechter and Nasir Shah!”

From the crowd: thunder. It’s like we’re at Bumbershoot on opening night, a wave of sound rolling off the audience. This theater is stacked with Annable kids who volunteered this weekend: timekeepers, moderators, tabulators. They are loud. They are many. But they are not the people we need to convince.

I lower my eyes to the judges, that sentry row right up front. They’re stone-faced, not clapping. How do we reach them? Make them love us?

Or, at least, love the bomb?

“And now, to open the final round of the N.A.D.A. Washington State Championship, arguing in favor of the resolution—‘This House would allow all states to possess nuclear weapons’—please welcome Jonah Cabrera!”

Jonah stands. There’s more of that polite, disinterested, away-game applause. But then he steps forward, and he shifts loose the tallest button on his dad’s Sunday-best blazer. And you can feel it: the audience falling, suddenly, just a little bit in love with him.

Understand: Jonah Cabrera is hot. I mean, objectively. He’s campaign-trail handsome, all square jaw and sharp cheeks and warm brown skin that goes almost gold when he gets some sun. Like a Kennedy from Calabarzon instead of Camelot. You look at him, and you want to keep looking. No, no, not just look; you want to listen.

“Good afternoon, Mr. Speaker, honorable opponents, guests,” Jonah says, and then pauses. “Or, should I say: Good afternoon, comrades.”

He tilts his head to the right. This is a private grin, just for me. I smile right back at him. A delicious, dangerous feeling blooms in my gut.

Like we’re breaking the rules.

Like we’re going to get away with it.

“The resolution before us today is, ‘This House would allow all states to possess nuclear weapons.’” Jonah clears his throat. Across the stage, the polite calm is beginning to slough from Ari’s face. “Today, we’ve decided to define ‘this House’ as the Security Council of the United Nations, circa 1955, and we’ve defined ‘nuclear weapons’ as . . .”

Ari Schechter leaps to her feet, arm flying out like a bayonet.

“Point of order!”

Jonah could stop talking. He could take Ari’s question.

He doesn’t.

“My comrade and I,” he says, “will be arguing on behalf of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, in the wake of the death of our great leader, Joseph Stalin.”

Ari brings her Gucci loafer down on the stage once, twice, three times: “Point! Of! Order!”

Annable’s headmaster, seated front and center, surrounded by judges, lowers his glasses. He lifts his hand.

“Yes, Ms. Schechter? You called for a point of order?”

“Mr. Speaker,” she says, her teeth a gritted cage, “my opponent has defined the resolution in such a way as to . . . to render this debate . . .” She stops, scowls, shakes her head, and tries again: “The definitions brought forth by our opposing team are not, I believe, in the spirit of the resolution.”

The judges tilt together for some debating of their own: Is Ari right? Have we broken the rules? Or is Ari coming across like a petulant preschooler throwing a temper tantrum in the Hatchimals aisle at Toys “R” Us?

In a world where Toys “R” Us wasn’t eaten alive by venture capitalists like her dad, I mean.

“Our judges have reached a verdict.” The headmaster, lifting his head from that huddle of judges, sounds—I think? I hope?—sad. A good sign for us. “So long as the definition doesn’t unfairly limit the terms of the debate—and the judges don’t believe that Mr. Cabrera has done so—the team from Johnson Technical is fully within their rights to define the debate in a historical context.”

“But . . . but . . .” Is that a wobble I hear in Ari’s voice? Is she about to start crying? “Mr. Speaker, if you remove the resolution from the post-9/11 epoch, you effectively strip it of—”

“Thank you, Ms. Schechter.” This is one of the judges, a woman with sleek black hair, raising her voice to speak over Ari. “You may continue,” she says, and smiles at Jonah, “Comrade Cabrera.”

The audience—this audience, so full of Annable students, so firmly with Ari and Nasir, so utterly against us—they actually laugh! Out loud! Ari crashes into her seat with murder in her eyes. Jonah turns to me, another tiny, private grin on his lips.

This one says, I told you I’d steer us right.

After the round, which was honestly less of a bloodbath than I would’ve liked, the four of us are ushered into a tiny white-brick chamber behind the stage. It’s what you’d call a greenroom, I guess, outfitted sparsely: a coffee table, a single threadbare couch. I’m keyed up after our near-hour of arguing, eager to sit down and relax. But Nasir is a step ahead of me. He dives vindictively for that single couch and sprawls out across all three cushions.

“Do you mind?” I ask him, tapping a tired foot. “I might like to take a seat.”

He doesn’t answer. He shuts his eyes, stretches his legs even longer, and points both middle fingers skyward.

Jonah laughs. “And the award for Miss Congeniality goes to . . .”

“Congeniality? Congeniality?” Ari sounds huskier than usual, pulling generous rips from a Juul the color of Pepto-Bismol as she paces the room. “You guys totally twisted the resolution in your favor, and you . . .” She stops, points her vape squarely at Jonah: “You referred to a genocidal dictator with a body count in the millions as a great leader.”

“Hey, remember when you asked the judges if we were breaking the rules?” Jonah leans against the white brick, giving her one of those broad, easy smiles. “And remember when they confirmed that we weren’t?”

“Exactly.” I’m still in the mood to argue. “You’re just mad you didn’t think of the Cold War angle.”

“You’re right. It never occurred to me to cheat.” She coughs, thick with phlegm. “Whatever. The top two teams at State automatically move on to Nationals. What more do you want?”

Says the girl who wants for nothing—including a spot at my dream school. The one she cheated to get.

“Remind me, Ari: How many buildings at Georgetown are named after you?”

“God, Finch. Get over it.” Even through the vapor, I can see her eyes roll. “It’s not my fault early admission kicked your ass. There were nine thousand kids competing for nine hundred spots.”

“Yo, keep it down.” Nasir pops out an earbud. “I’m trying to bid on this Twitch streamer’s bathwater.”

I ignore him. We all do.

“And you don’t think you had a leg up on the competition, Ari?” I step toward her, into her fog. “Sitting on your ass while your dad wrote check after check after . . .”

Her eyes are still rolling. “He wrote one check, Finch.”

I yelp so hard my voice cracks: “For forty million dollars!”

“Really?” She exhales purply. “I thought it was fifty.”

I sort of lunge at her—to do what, exactly, I don’t know. I’ve never been in a fight, and I’d definitely lose. Ari’s twice my size—taller and stockier. I’m a twig next to her. Lucky for me, Jonah’s cooler head prevails. He puts his hands on my shoulders. He pulls me back.

“Settle down, guys.” He says this to me and her both. “Not the time for a fistfight.”

“No, of course not,” Ari says, shaking her head. “You’d probably find a way to cheat at that, too.”

At my sides, against Jonah’s advice, my hands curl into angry fists. “We did not cheat.”

Just then, the room’s one and only door begins to open: the winged tip of the headmaster’s shoe steps in. Ari fumbles to stash her Juul, Nasir pushes his phone into his pocket, and I shake my fists back into hands. By the time the door’s all the way open, the four of us are standing at attention, model students. If the headmaster notices the violet mist circling Ari, he doesn’t let on.

“Ms. Schechter? Mr. Shah?” He turns to me and Jonah, thinks hard—no paper to read from, not this time. “. . . Others?”

“Mr. Kelly,” I offer, and Jonah supplies, “Mr. Cabrera.” The headmaster smiles falsely, sweeping his arms to the open door.

“Wonderful,” he says. “We’re ready for you.”

“What a spirited, rigorous final round to conclude this tournament.”

The headmaster glances over his shoulder, and grins at Ari—who’s struggling, with ballooning cheeks, to contain a vapory cough—and Nasir. No smile for us, though. Fine. Let him count us out. It’ll be that much sweeter when he rips open that envelope and reads our names.

“Without further ado,” he says, “it is my pleasure to announce the winners of this year’s Washington State Senior Debate Championship.”

His fingers click lightly against the wood of the podium—the one percent’s version of a drumroll, I guess. He takes the envelope in hand. He tears it open.

And just as I’m readying myself to rise to my feet, he says, “Congratulations . . . to Ariadne Schechter and Nasir Shah!”

I don’t rise. I don’t breathe. I can only watch as Ari and Nasir stumble to the front of the stage, stupefied, to accept a trophy the size of my body. I look to my left, to Jonah, only to find that he’s already looking at me, bewildered.

“Second place,” he says, tentative. “Second place still goes to Nationals. Second place is . . . fine. Right?”

Wrong, I want to tell him. Second place is not good enough. Not for me, not for us, and definitely not for Georgetown.

But I don’t answer him. I can’t. For the first time all day, the power of speech has deserted me.

chapter two

“How’d it go, champ? Didya kick some Annable ass?”

Dad’s blurry in the lens of the living room desktop, scratching at the midlife crisis on his chin. He calls me “sport” and “champ” a lot—all in the name of, like, masculine affirmation. I don’t mind it, usually, but I lost the right to call myself a champ today. Lost the right publicly, mortifyingly, in front of hundreds. I wince, remembering; Dad catches it.

“What’s the matter? Why are you making that face?” He’s leaning forward, brow folding, a storm gathering. “Did one of those spoiled brats say something about your clothes again?”

“Is that Finch?” Behind Dad, I see a flurry of flannel: It’s Mom, pulling up a chair, peering at the webcam. “What’s wrong, honey? You don’t look happy.”

When the spotty discount-hotel Wi-Fi allows for it, I usually video-call my folks after tournaments. But I’ve never briefed them on a catastrophe before. I’m not sure how to do it. And I’m not sure I want to, either—deliver bad news to people who don’t need another ounce of it.

Just then, while I’m searching for words, my little sister arrives in the frame. She rakes back her hair—once as red as mine, recently box-dyed black.

“Wait. Did you guys lose?” she asks, disbelieving. I nod grimly. She lets out an emphatic: “Fuck.”

Dad calls out—“Ruby! Language!”—but his heart, I know, isn’t really in the scold. To judge by the dark cloud gathering on his brow, he’s ready to curse out Annable himself.

“Well?” Mom, an arts reporter for the Mountain, knows her way around a tough interview. “Can you tell us what happened?”

Should I lie? Coat the whole thing in sugar, at least? No, no; Mom would interrogate the truth out of me. Better be honest about this, about who I am now: a loser. A person who loses.

“Annable beat us in the final round, yeah.” I scratch at a dehydrated zit on the side of my nose. “Not sure how badly. We won’t know until we get our ballots back.”

“Oh, Finch, sweetie,” Mom coos. “I’m so sorry. You must—”

“What about your college apps?” Dad interrupts. “You were gonna send those D.C. schools your results from State, weren’t you? Try to drum up some extra scholarship dollars?”

Good to know I can always depend on Dad to speak my deepest anxieties aloud.

“Well, we did come in second,” I begin, slowly, trying to smile. “So we’re still advancing to Nationals. That’s something, at least.”

Jonah said this to me earlier, on the stage, when the loss was still fresh. But it’s only now, repeating it out loud, that I realize: Second place is something. Nationals is something, too. Don’t I deserve to be proud of these somethings? At least a little?

“But you can’t go to school in D.C. without a full ride,” Dad says. “We don’t have it like that, kid. We’ve talked about this.”

We have. We have talked and talked and talked. Apparently not enough, though; Dad never misses a chance to shake salt on this particular wound. He and Mom are lobbying me to look in-state, but I’ve got my heart set on the other Washington, the one where progress happens, where good people fight the good fight, where history breathes in every brick. Georgetown is my dream school, but I’ve applied to American, too, and George Washington. I just want to be there, you know? I want everything the city has to offer.

And, of course, I want to huck a carton of cage-free eggs at Mitch McConnell’s brownstone. No school in the Seattle area will give me that.

“Dad. Please. I know.” I’ve got a bad habit of going single-syllable when he grills me like this. “I do my best. I work hard. This was just a bad day.”

“Everything counts right now,” he says, not listening. “Every grade. Every test. Every tournament.”

I catch his glare. I swallow. I no longer have even a single syllable in me. So I go mute. I lift a hand, find a peeling hangnail. I chew.

“Jesus Christ, Mitch, would you ease off him?”

“What? What’d I do?”

“He just lost his big round. Maybe save the lecture for another day.”

“Well, if he’s got his heart set on these Ivy League schools all the way across the fucking country, he’s gonna have to work for . . .”

“Ughghghghghghghghghghghghgh.” Roo moves close to the camera, peers at me through fingers curled into claws. “They’ve been like this all weekend, Finch. Come home. Rescue me. Please. I’m fucking dying.”

“Okay!” Mom calls out. “That’s it!” She and Dad can fight all they want—all day, all night, apocalyptically—but God forbid Roo drop an f-bomb. “Go to your room, Ruby.”

“Seriously?” Her eyes, made up in clumsy, raccoonish circles, roll and roll. You’re the ones going World War Three in front of Finch.”

“Go. To. Your. Room.”

“Fine. Whatever.” Roo lifts her hands, half hidden in the long sleeves of her hoodie, and rises. “Sorry you lost the round, Finch. Tell that girl from Annable to go suck a—”

“Ruby!”

With that, Roo’s gone, off-camera, before I can blink. There’s a faint echo in my headphones as she stalks heavily into her room.

Mom says, “Sorry about her,” and I tell her, “It’s fine, really,” because if there’s one thing I can’t stand, it’s my parents confiding in me about how difficult Roo can be.

“Well, hey,” Dad says—spilling salt into my wounds, still, “if you win Nationals, those D.C. schools will open their pockets for sure.”

“I hope so.” Even though I’m bruised from this tournament, I’ve already started plotting for the next one. “There’ll be some stiff competition from those boarding schools out in New England, but . . .”

“Hey, Finch! Shower’s all yours!”

I was so caught up in my call that I missed the bathroom door clicking open. But it’s impossible to miss Jonah emerging—ringed in a cloud of pale steam, towel riding dangerously low. I slap a palm over my webcam. I do not want Mom and Dad to see what I’m seeing.

“Finch?” Mom calls out, disoriented. “You still there?”

“Yep!” I chirp. “Sorry. Just having an issue with the camera.” Jonah bends over a suitcase, his towel slipping even lower. I will not be moving my hand anytime soon. “Can I call you later? After the banquet?”

“Sure thing, sport.” I’ve never played a sport in my life. Dad knows this. “Hang in there.”

“Thanks,” I tell him, and forcefully end call.

The danger is past. Jonah is pulling his pants on.

“Congrats,” I say. “My parents officially know you’ve been working out.”

Jonah laughs and whips his towel at me. I dodge it, but just barely. It meets the mattress with a lewd, wet smack.

“I’m actually super out of shape right now,” he says, which, of course, is a lie, because I saw his biceps flex when he whipped that towel. They are right there, shimmering with little drops of water from the shower. It’s honestly obscene. “No musical this year means no boyfriend busting my ass in dance rehearsals. I’m getting sloppy.”

“Seriously, Jonah?” I lift a hand, gesture at his . . . everything. “In what world is that sloppy?”

It comes out more bitter than I mean it. I just can’t help feeling jealous, looking at Jonah, all lanky, all sun-kissed. Someday, Blue Cross willing, I’ll sculpt my body into something I don’t despise. But all the surgery in the world won’t make me taller. Or smooth my frizzy hair. Or keep my paper-white Irish skin from igniting at the mere suggestion of sunlight.

Jonah’s boyfriend, Bailey Lundquist, the star of Johnson Tech’s drama department—he’s pale, too. Paler, even, than me. There’s something delicate, elfin, about his features. It can be off-putting sometimes, a little alien, but he looks good next to Jonah. Among their Halloween costumes in recent years: a medieval knight and a fairy prince; a swashbuckling pirate and a deep-sea merman; Jon Snow and Daenerys Targaryen, with Jonah’s beloved mutt, Toto, tagging along in papier-mâché dragon wings.

“Well, hey, look on the bright side,” Jonah says—maybe hearing that bitter note in my voice, maybe trying to cheer me up. “We lost the final round, but we won something way more important.”

“Really?” I perk up. “What did we win?”

“Two tickets to the gun show, baby!” he says, and lifts his arms, curling them like a bodybuilder.

“I hate you.” I toss a pillow at him: right in the abs, bull’s-eye. “Put a shirt on.”

“I was thinking blue for the banquet,” he says, tossing the pillow aside, bending over his suitcase. “And maybe my Hamilton hoodie for Nasir’s after-party. The one that’s like, ‘Talk less, smile more.’”

I laugh. “Good advice for Nasir.”

“You know what?” Jonah lifts his head, points. “You should come with.”

“Come with? You? To Nasir’s party?”

“Yes to all three.”

“. . . Why?”

I’ve never been to one of Nasir’s blow-out bashes. You may have already guessed, given that nobody in the history of parties has ever referred to one as “a blow-out bash.” But I’ve heard stories of the carnage: bones broken, babies conceived, tiled floors turned oil-slick with beer and bodily fluid. Not exactly my scene.

“A party might cheer you up,” he says. “Take your mind off the final.”

“Even though the party’s host destroyed us in said final?”

He doesn’t answer; I’ve won. And so I smirk, and make for the shower. “Hope you didn’t use up all the hot water.”

“Please,” he says. “You know I only do staggered showers.”

I do know this, actually, from all our past stays at Super 8’s and Quality Inns. I still like to tease him about it. “Sounds miserable, Greta.”

“You know what? Just for that, I’m timing you while you’re in there.” He taps his wrist, an invisible watch. “Tell you exactly how much water you’re wasting.”

I scowl at him—so I like long showers; sue me!—and step into the bathroom. There’s only a little steam in the air after Jonah’s brief round of room-temperature water torture, but I still have to lift my hand to clear the mirror. When I get a look at myself, I’m surprised: There’s a strawberry-blond shadow sprouting on my chin. It shocks me every time, still. I wonder how I’d look if I let it grow into a beard. Scraggly? Pubertal? Deeply unconvincing?

I sigh. I reach for the razor.

After eighteen months of testosterone and a year of puberty-delaying Lupron, I’m finally able to pass . . . as a thirteen-year-old boy. I get a lot of kids’ menus. A lot of well-meaning strangers being like, “Are you excited to start high school, young man?” I don’t love the “young,” but I’ll take the “man.” It’s all I’ve ever wanted. People look at me, and they think “he.” They think “him.” They don’t think about it.

I do, though. I think about it. Especially when I’m alone like this. I meet my own eyes in the mirror and I pick myself to pieces. Are my cheeks too round? Is my jaw square enough? Should I cover my acne, or would strangers catch the makeup and think “girl”?

The best way to banish all these questions is to step into the shower, tilt the dial all the way up, and let the jets sear me. This is how I prefer to unwind. Not partying. I’ve never been to one of Nasir’s ragers, but given the sure-to-be-copious amounts of alcohol, and given Dad’s history with the stuff, shouldn’t I steer clear?

I don’t know. Maybe it’s the hot water pouring over me, calming me down, but I’m beginning to think Jonah’s onto something. Wouldn’t some music and movement put me in a better mood? I could avoid beer, couldn’t I? Drink Sprite. Dance, even, if my back stops killing me.

That reminds me: I’d have to bind all night, wouldn’t I? I do not want to put my binder back on. For the first time all day, I can actually breathe: all the way in, all the way out. Nothing is pushing down on my chest, my ribs, my little lungs. The price of this relief, though, is being reminded. Of them. And how obvious they are. And how obviously wrong for me. I’ve got my surgery scheduled for this summer. It can’t come fast enough. In the meantime, though, I bend beneath the showerhead and let the heat strike the sorest spot, right between my shoulders, where the binder’s been pressing all day.

I’m reminded, bending, looking at the long streams of water racing down my legs to my ankles, that I haven’t cried today. Not once. I should be crying. Shouldn’t I? Debate is the one and only place where I’m invincible, where I can talk circles around anyone, about anything. And I lost! I lost the state final! One of those rounds that truly matter. A round that would’ve meant something to the admissions committees of Georgetown and American and George Washington. I’d like to cry about it. Really, I would. I wish I could squeeze my eyes shut and wring everything out: the anger, of course, but the fear, too, and the embarrassment.

This is the thing about taking testosterone, though, the thing nobody ever tells you: Some guys, through some bizarre confluence of biology and chemistry and endocrinology, lose the ability to cry. You still get sad, of course. You still get that hot, familiar ache behind your eyes, and that same old tightness in your throat. But you can’t actually make your sorrow real. The water never shows.

Speaking of water, I’ve used way too much of it. If I don’t exit the shower soon, Jonah will give me one of his . . . well, no, lecture isn’t the word. Guilt trip, more like. Whatever it’s called when your debate partner pulls out his phone and takes you through the greatest hits: turtle with plastic straw jammed bloodily into nose, seahorse curling perfect tail around Q-tip, skeletal polar bear shambling pathetically over tundra of trash.

Manipulative as hell? Yes. Unbelievably effective? Also yes.

I step out of the shower. Before I can grab a towel, I catch a blurry glimpse of myself in the mirror. The twin peaks of my chest rising and falling. I turn away. I wish—not for the first time—that I lived in a different body.

In the hall, at the mirror, Jonah’s trying—well, failing—to do up his tie. It’s kind of funny: Jonah, who’s been a bona fide boy all his life, can’t pull off a basic knot to save said life. But me, the guy raised in ruffles and bows? I’ve got it down.

Jonah looks jealous as I pull up next to him, tugging my tie effortlessly into place. “How are you so good at this?”

“I practiced the Windsor knot ’til my fingers bled,” I tell him. “Trying to hide the fact that I don’t have an Adam’s apple.” He laughs. I beckon him closer. “Come here. Let me work my transmasc magic.”

He turns to me. The ends of his tie hang long and loose. “Do your worst,” he says as I take one end—stripes, blue and red—and the other—white, studded with a golden starburst—in my hands.

“What’s this pattern?” I ask. “I want to say the Stars and Stripes, but the colors aren’t quite . . .”

“Yeah, no, it’s the flag of the Philippines,” he says. “My dad gave it to me for this tournament. I wanted to pull it out tonight as, like, a very subtle middle finger to the judges who look at me and think, ‘No way this kid speaks English.’”

I know exactly what he’s talking about. It happened more when we were younger—ninth graders, newbies. But even now, with our shelves of trophies, we encounter the occasional judge who frowns when Jonah enters the room, before he’s even begun to speak. Or a moderator, maybe, who reads the rules just a little too slowly. Sometimes we’ll even get an opponent who compliments Jonah, during the courteous round-concluding handshakes, on his lack of an accent.

“You’re better than all of them.” My hands go still on his tie. “You know that, right?”

I look up, waiting for a smile. A nod. Something to let me know he understands me. Instead, he says, “I’m sorry.”

I frown. “Sorry for what?”

“The Soviet thing,” he says. “That’s what sank us. And it’s my fault. A hundred percent. I take full responsibility.”

I look down: my hands, his tie. I can’t meet his eyes. How, how does he think the loss is his fault? It’s mine, I think, my fault, instead of paying attention; I miss a crucial step in the knot, botch the whole thing. The thin tail’s dangling loose, all the way down to his belt.

“Don’t apologize.” I pull the knot apart, smooth down the red and blue and gold. “We lost because I wasn’t ready for Ari’s proxy war argument.”

“No, no. You covered all your bases.” Jonah sighs. “She didn’t have a comeback when you brought up imperial overstretch. Your whole Paul Kennedy spiel was great.”

“Didn’t slow Nasir down,” I mumble, in no mood for compliments. “Remember when he was all, ‘The same Paul Kennedy who made his way onto Osama bin Laden’s bookshelf?’”

“God, that was such a dick move,” Jonah says, and shakes his head. “You know what else they found on bin Laden’s hard drive? Like, fifty episodes of Naruto. Does that make Sasuke a terrorist? Wait. No. Bad example.”

“Hold still,” I tell him, because he gets excited when he talks about anime, waving his arms around. “Don’t move your shoulders.” I tighten the knot at his neck. “And don’t blame yourself, either.”

He lets his hands fall to his sides. “I just . . . I know how much this meant to you. Because of Georgetown. And D.C. And . . . everything.”

“Well,” I breathe out, and tug his blue collar. “We can still take Nationals.”

“Damn right, dude.”

We smack our palms together—a high five that feels like a promise.

“Well?” he says. “Ready to go? We don’t want to be late for the banquet. Or the after-party.”

“Oh, I can’t wait,” I deadpan, following Jonah out the door. “Tonight’s the night I finally find out what a party looks like.”

But my pan must have been too dead, because Jonah looks back at me, over his shoulder, with wide eyes.

“Wait,” he begins, slow, trying to figure me out. “Are you serious? You, Finch Kelly, the calmest nerd alive—you want to come with me? To a Nasir Shah rager?”

Am I serious? I don’t know. I was in the shower a long time, talking myself into this party and right back out of it. I could stand here even longer, going back and forth with Jonah, picking over the pros, the cons.

But I’ve been debating all day. I’m tired of talking. And so I shrug, and I give Jonah a single, simple syllable: “Sure.”

“Yes!” Jonah pumps his fist. “You and Ari can finally do something about all that sexual tension.”

I shove him, hard, through the open door. He laughs and shoves me right back. We stumble out into the hall, throwing punches too soft to really land.

We arrive at the party a little less than an hour late. Blame Seattle’s buses. The sky is blacker than black above the sleek steel-gray mansion Nasir calls home, and the festivities are in full, grisly swing. I take a balletic little leap over a puddle of oatmeal-y vomit to get at the doorbell. There’s a terrible sound like a swarm of buzzing horseflies before Nasir throws the door open: turquoise shutter-shades, no shirt. “’Bout time,” he shouts. “Ready to get fucked up, my [hair-raising racial slur Nasir’s got no business deploying]s?”

Before I can ask where he’s taking us, or complain about the hair-raising slur, Nasir’s ushering us through a gleaming white foyer into an even more gleaming and white kitchen the size of an airline hangar. He sweeps his arms across a countertop cluttered with glassy alcoholic bottles—and a single dented carton of Tropicana.

“That’s for me,” I say, and pour myself a tall orange glass.

“Yo, what the hell?” Nasir grimaces at my juice. “You’re drinking straight mixer? Who does that, man?”

“Don’t worry, Nasir,” says Jonah, hand around the neck of a green-bottled beer. “I’ll drink enough for the both of us.”

“Won’t you get all red in the face, though?” Nasir asks, sincerely. “Since you’re Asian? Or is that just chicks?”

Jonah takes a deep breath—a long one, almost exactly to the count of five. “Nice chatting, Nasir.” And then, before I can protest, or beg him to stay, he’s gone.

He hasn’t left me alone with Nasir. Not quite. There are maybe fifty people packed into this kitchen—debaters I recognize, volunteers I don’t. The girls are in the same slinky stuff they wore to the banquet, and the boys have pulled their ties loose, rolled their sleeves to their elbows. They’re pouring beverages, belting off-key to pop songs I can’t place, carrying on drunk versions of the arguments we’ve been having all day. They look at home here. Comfortable. Like the leap from podium to party is the most natural thing in the world. Where does that confidence come from? And where can I find some?

Nasir nudges my side. Lucky me. In this whole, wide room, I’m his only conversational target.

“So, what’s with the O.J.?” he says. “Why don’t you drink?”

I hit Alateen meetings with Roo every week. I know exactly how to handle this question. “Well, not many people know this, but alcohol causes cancer,” I tell him. “The World Health Organization actually classes it as—”

“But you’re Irish, right?” He ruffles my red hair. “I thought you guys loved this shit.”

Seeing as we’re at a house party in the twenty-first century and not, like, Ellis Island, the abject Hibernophobia catches me off guard. Alateen didn’t prepare me for this one. I have no idea how to answer him. And before I can figure it out, I hear a familiar voice: “Fuck’s sake, Nas. Leave the ginger alone.”

I turn to see Ari Schechter at the tap, filling a glass slowly to the brim with water. Unlike every other girl in the room, she didn’t dress for a party. She didn’t even change out of her uniform. She moves through the crowd to us, plaid skirt swaying. Does she know how strange she looks? How out-of-place? Does she care?

“Rodham!” Nasir crows, thumping her broad back. “Thought you weren’t coming out!”

“I never pass up a victory lap.” Ari grins at me, smug. “How you feeling, Finch? Didn’t see that verdict coming, huh?”

Remind me: Why did I think this party would cheer me up?

“And we’re gonna hit you again at Nats!” Nasir lifts his bottle, lets out a jubilant shout: “Bé salamati!”

I don’t join his toast. Neither does Ari.

“Teams from the same state don’t debate each other in regular competition at Nationals,” she says, all matter-of-fact, “which you’d know if you ever opened my emails.”

“Ugh! Don’t kill my buzz!” Nasir shuffles back, spilling beer. “This is a party! I gotta find me some Pootie Tang!”

I look at Ari, baffled, as he caroms out of the kitchen. “What’s he talking about?” I ask her. “Pootie Tang?”

“He means poontang,” she says, and sighs. “Derogatory slang for the vagina. From the French putain, or prostitute.”

“Oh,” I say. “I see.”

We both go quiet. Ari sips her water. I sip my juice. There’s a feeling, as the party flows around us, like we’re stuck at the kids’ table during a family gathering. Everyone else is having abundantly more fun than we are. Just like that, we’re not arch-nemeses anymore—only the two most boring people at this party.

“So, hey,” she says, leaning into me a little. “About that thing in the greenroom earlier.”

I give her a sidelong look. “When you accused us of cheating, you mean?”

“I was out of line,” she says. “I mean, sure, I didn’t love you guys setting the debate in the Soviet Union. But also, like . . .” She sighs, shrugs. “Fair play?”

“Wow.” It’s almost an apology. I’m impressed. “Are we having a Camp David moment?”

“Oh, no.” She laughs, falls away from me, shaking her head. “Not at all. We fully deserved to win. I concede only that my hissy fit was a bad look. Unsportsmanlike.” She pauses, tapping the rim of her glass against mine—a tentative, non--alcoholic toast. “So: No hard feelings?”

“Oh, no.” I pull my glass away. “My feelings are very hard.”

Her dark eyes go wide, and she says, “Um,” which makes me realize what I’ve said, which makes me open my mouth and go, “Not . . . not like . . . I didn’t mean . . . I wasn’t trying to, uh . . . to like, seduce you, or . . . or anything like . . . like . . .”

“No, yeah,” Ari giggles. “That was very clear from your complete and utter lack of game.”

“I have game!” I step forward, spilling a sip of orange juice on the floor. “I definitely have game!”

“Totally,” she says. “Spilling orange juice? Tried-and-true seduction tactic.”

“That was an accident.”

“Well, I’m still waiting for the receipts.” She sips coolly from her tap water, lifts a suggestive brow. “Some proof of this alleged game.”

I start to speak—“What are you . . .” but before I can even land on talking about, I realize: Ari might be hitting on me.

I mean, I think she is. Was Jonah right? Is there . . . tension between Ari and me?

I turn away from her. I look at the tiled floor. The clean white walls. The bottles cluttering the countertop. Anywhere but Ari. If I’m right, if she is flirting with me . . . well, that’s awfully suspicious, isn’t it? Not only am I her worst enemy, I’m . . . well, I’m me. Not exactly what you’d call a catch.

In the entire course of my life, I’ve only ever had one girlfriend: Lucy Newsome, a lesbian who laid me off the second I came out as a boy. (The breakup was amicable; she’s now my best friend.) Nobody’s ever flirted with me. Let alone at a party. A party at a bona fide mansion with plenty of bedrooms upstairs.

What would even happen if I ever found myself in a bedroom with a girl? Would she want to kiss me? Touch me? Peel off my clothes? Her hands would find the binder. She’d scream. Reel away from me. Tell all her friends that I . . . that I’m . . .

I need air. I need help. Where the hell did Jonah go, anyway?

“Can I . . . I just . . . I need to go find Jonah. Just touch base.”

“Sure. No worries.” Ari’s got her phone out. I look at her; she looks at the screen. “See you later, I guess?”

I guess? What does that mean? Does she want to see me later? And why am I agonizing like this over Ariadne Schechter of all people?

I don’t know. I can’t say. I need to find Jonah. He’ll know what to do. About Ari. About all of this. Even though he’s gay, even though he’s never been with a girl—he’ll know. He’s confident in all the ways that matter. All the ways I’m not. He knows me. He’ll know how to calm me down.

And so I go looking for Jonah. It takes longer than I’d like. I peer into devastated bathrooms, climb beer-sticky stairs, interrupt no less than half a dozen drunk debates. Real intellectual variety here: A big group over by the pool table wonders where you put all the rapists if you abolish prisons; some guys in line for the bathroom argue about which YouTube starlet is operating the most worthwhile OnlyFans.

I finally find Jonah out on the balcony, facing south against the skyline. The view here’s worth millions: Space Needle, skyscrapers, snowcapped mountains rising through the clouds. He’s a tiny black silhouette against all this splendor.

I’m just about to step through the screen door when I see he’s got his hand to his ear. There’s a glint: a phone. I pause behind the mesh. Should I leave, I wonder? I don’t want to eavesdrop.

Until I hear my name.

“No, no, Finch was flawless. The whole thing was my fault.” There’s a pause. He listens; he laughs. “God, Bee, how do you always know the exact right thing to say?” Another pause—longer, this time—as he listens to his boyfriend’s voice. “Right. Exactly. Not a total wash. We’re going on to Nationals. We still got silver medals.” A puff of breath, visible in the cool March air. “Enough about me, though. How are you? How was your rehearsal? Did you run through your duet with . . . Oh, awesome. I can’t wait to see it. I can’t wait to see you.” He sighs; the hand with the phone falls from his ear.

I’m just about to step forward, join him on the balcony, when I hear a crackle of static. Jonah’s holding his phone aloft, dangling it daringly over the railing. “Can you see it?” he says, and it’s then, only then, that I realize what he’s doing: filming the skyline for Bailey. “Mount Rainier, right there, behind that cloud?” I can’t hear what Bailey says in reply, not from where I’m standing, but Jonah seems touched by it. “I’m so glad you picked up,” he says. “I get so lonely at these things.”

Jonah sounds a little strange, different than he does when we talk. I’ve never heard his voice this low, this loving. It’s so big, this thing he’s got with Bailey. So much brighter than anything I’ve ever felt for anyone.

“I miss you,” Jonah says. He waits a moment; he says, “I love you, too.”

None of this is a mystery to him. He’s figured it out. All of it. He’s in love.

And here I am, a total infant, too afraid to even hook up with a girl at a party.

I retreat, fast, before Jonah can see me. I don’t return to the party. I don’t wish Ari a good night. I shuffle, instead, out a side door, and down a long driveway. And then, alone, on a vacant side street, I climb onto an empty city bus and head to the Holiday Inn.