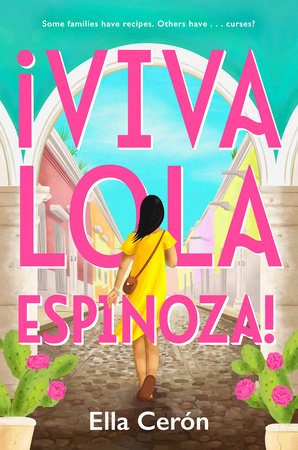

Viva Lola Espinoza

Ebook

$8.99

PRAISE for Viva Lola Espinoza by Ella Cerón:

2024 Texas Tayshas Reading List

"...a rollicking fun read."—Publisher's Weekly

"This novel will resonate with readers who understand the difficulties of breaking out of their comfort zone, especially when it comes to conquering the obstacles of love and parents. Cerón’s beautiful tale is a reminder that life lessons often come from outside of schools, books, or snapshots."—Booklist, STARRED REVIEW

"The story thoughtfully touches on identity and heritage: Lola’s paternal grandparents were undocumented, Papi attended college in Mexico, and Lola feels sensitive about her language struggles. It also explores colorism in Latine communities; Lola has tan skin, Rio is light-skinned, and Javi, who has a darker complexion, has a Zapotec mother. A tender coming-of-age story about family and first love." —Kirkus Reviews

2024 Texas Tayshas Reading List

"...a rollicking fun read."—Publisher's Weekly

"This novel will resonate with readers who understand the difficulties of breaking out of their comfort zone, especially when it comes to conquering the obstacles of love and parents. Cerón’s beautiful tale is a reminder that life lessons often come from outside of schools, books, or snapshots."—Booklist, STARRED REVIEW

"The story thoughtfully touches on identity and heritage: Lola’s paternal grandparents were undocumented, Papi attended college in Mexico, and Lola feels sensitive about her language struggles. It also explores colorism in Latine communities; Lola has tan skin, Rio is light-skinned, and Javi, who has a darker complexion, has a Zapotec mother. A tender coming-of-age story about family and first love." —Kirkus Reviews

- Pages: 400 Pages

- Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

- Imprint: Kokila

- ISBN: 9780593405635

An Excerpt From

Viva Lola Espinoza

Twenty-seven minutes before the end of the last study hall period of the spring semester, a folded-up piece of paper landed in front of the book Lola Espinoza was halfheartedly reading.

Okay, she was using the book to hide her phone as she refreshed it. She wanted to be notified the second her grades hit her inbox. Not that she wanted to get her grades back. She just wanted to be aware.

She turned in the direction the projectile missive had come from and found Diego Padilla staring confidently at her. Diego—Padilla, as his friends called him—was one of the most popular boys in school and had been on the varsity soccer team since freshman year. Everyone knew Padilla. This was the first time he had ever indicated that he knew Lola existed, and they’d been in the same class since third grade.

Lola unfolded the note: My party—u in?

She read the words, barely legible in their smudged, stick-letter scrawl, again. Was she really being invited to the biggest end-of-semester party in the whole high school? She balked, buffered, and mentally reset. No, this note must have been for Ana, who always sat one seat over from Lola at the shared library table during study hall. Susana Morris was friends with everyone, a human disco ball refracting her light onto everyone around her. She was also, crucially, Lola’s best friend.

Lola glanced at Padilla and motioned to confirm that he wanted her to pass on the note. He raised one eyebrow and shook his head.

Ana, who had been furiously shuffling a deck of oracle cards behind the book that served as her shield from Mr. Wesley, saw Padilla’s facial expression out of the corner of her eye and snapped her attention toward the piece of paper in Lola’s hand. “Is that a letter? From Padilla? What does it say?” She pushed the deck to the side and grabbed at the note. Her eyes lit up instantly. “You have to come with me.”

Lola almost laughed at the thought. The last time she’d been to a party with Ana, she’d bopped her head awkwardly in the corner of someone’s parents’ living room before slipping out half an hour after she arrived. Could you classify it as “sneaking out” if only one person noticed you’d been there? Lola wasn’t sure.

“There’s no way I’m going,” Lola replied. “No, let me clarify. There is no way I would even be allowed to go.”

Ana sighed. “Come on! I can’t remember the last time you didn’t bail on a party, and we’re going to be seniors next year. And Padilla invited you personally. The rules of high school dictate that you are obligated to attend.”

Lola grabbed the note back. “Why would he do that? I didn’t even think he knew who I was.”

“C’mon, Espinoza. The two of you have been in the same school since before we were friends. He knows.”

“But Padilla?”

“I don’t get how boys’ minds work—let alone the minds of boys on the soccer team—but sure, why not? You’re cuter than you give yourself credit for. At some point, someone was bound to notice you. It’s calculus or probability or whatever,” Ana said matter-of-factly, picking the deck back up to shuffle it. A girl she’d been on three dates with had given it to her as a gift two years ago, and she’d gotten particularly obsessed with pulling a card before each final exam that semester, predicting how the test would go.

The verdict was still out on whether such a ritual worked or not. Grades were due by the end of the day, and Lola’s phone had not yet buzzed, alerting their arrival.

Lola glanced over at Padilla again. Though she made the most thorough study guides of anyone in their grade, she did not have a road map for this. Boys didn’t notice her, much less ask her to parties. The probability that they would was almost zero, and had been her entire high school career.

Not like she minded—anonymity gave her time to focus on homework. And while she spent her weekends watching makeup tutorials on YouTube, she always wiped off her handiwork before she left her bedroom. Not being known for her prowess with a cut crease ensured that her most defining trait at school was being Ana’s best friend, as she had been since they’d sat next to each other in homeroom at the start of the seventh grade and Ana had forced Lola into having a conversation.

Their friendship was one of contrasts: Ana was on the cross-country team in the fall, the basketball team in winter, and doubled up on track and swim in spring. She was both the first one to make a joke in the middle of class and to rush to the center of the gym floor at every school dance. Ana lived for the spotlight—it only made her more formidable—while Lola fell to pieces if she had to speak during a group project presentation. During lunch, Lola studied in the corner of the quad while Ana made her rounds, only settling down so she could fill Lola in on whatever new drama had upended their classmates’ lives. Lola liked it that way. She had a social life by proxy, with none of the stakes of actually getting involved.

In the four years since they had been friends, most of their classmates only ever acknowledged Lola when they wanted to get closer to Ana. There had been only one person who broke that mold: Christopher Yoon, whom Lola had sat behind in eighth-grade math. He was funny and owned the room the way Ana did; he gave everyone the same megawatt smile, and it made Lola’s kneecaps disintegrate whenever she found herself somewhere in its light. He was the perfect boy to have a crush on because everyone had a crush on him—and because the only idea more terrifying to Lola than telling her parents she’d gotten a bad grade was asking if she could go out with someone.

She needed a crush like Chris. A safe one that was meant to be unrequited. That way, nothing could ever come of it, and she wouldn’t have to be disappointed.

So when Chris asked Lola to partner with him on a geometry project, she heard herself saying yes even though the correct answer—the safe answer, and the one that her parents would expect her to give—would have been no.

It was that afternoon in the library when Lola learned how dark brown his eyes were, and that holding Chris’s attention felt like the most special thing she could ever do. When he leaned over their textbooks and kissed her, her mind went blank . . .

And then she was hit by a wave of nausea so violent that she had to run to the bathroom before she deposited her entire lunch all over him.

Her parents assumed she had food poisoning and let her stay home from school the next day, a rarity in the Espinoza house. But she had to go back to school eventually, and she asked Sophie Acosta to switch seats in math when she did. Sitting within even a mile’s radius of Chris made Lola’s face grow as pink as her least-favorite blush. How could she have failed at her first kiss? Chris hadn’t seemed to mind—he and Sophie started dating the following week—but Lola didn’t forget so easily.

When she talked to Ana about it afterward, Ana brushed off the incident as bad luck and pointed out that at least the kiss was memorable in its own way. Ana’s first kiss, with Tara Guzman that same year, had been pedestrian by comparison; Lola had a story.

Yet Lola couldn’t help but feel like she’d somehow been cursed to spend her high school years doing homework in an endless spiral, an academic purgatory with no salvation in sight. She studied so she could sign up for more AP classes so that she could then study for the next test, and the next one. There was no time for mall hangs, or homecoming dances, or parties, or, God forbid, a relationship. None of those things would get her into a good college on a scholarship, her parents often reminded her. And while Lola liked being smart, she also couldn’t shake a specific sense of dread that she could be missing out on a world that existed beyond What Her Parents Wanted for Her.

Then again, Lola’s identity was so wrapped up in school, she wouldn’t even have known how to be anything other than a good student. Who was Lola Espinoza outside of that? She wasn’t sure she even existed beyond the pages of her textbooks, or as the weird moon orbiting awkwardly in Ana’s solar system. Really, the only logical thing to do was tuck any hopes of a social life—let alone romance—away and focus on her schoolwork.

She told herself she was fine with it.

And most days, she was.

Lola quietly folded up the note, but Ana snatched it out of her hand and scribbled something on it before Lola could put it away. “Live a little!” Ana had written below Padilla’s invite, her effortless loops a direct counter to his handwriting.

Lola tried to suppress the small feeling growing inside her. The part of her that wanted to work up the nerve to ask her parents if she could stop by for an hour, the part of her that might actually want to go.

“It’s just a party.” She sighed.

“Exactly. It’s just a party. So you should just come.”

Lola sneaked a glance at her phone. Maybe if her parents thought her grades were good enough this semester, she would take Ana up on an invite or two this summer. Maybe, maybe, it would be fun to socialize—at least in a low-stakes, non-romantic, non-distracting-from-studying way.

An email notification from the Oxnard school district appeared on her phone screen.

Lola took a deep breath as she pressed the link.

She stared at the screen in front of her and kept refreshing the page, hoping it would change.

It didn’t.

B

Lola Espinoza was not a C student. Lola Espinoza was not allowed to get C’s, or even B’s, not even an 89 percent. It was A’s or nada.

Papi would not understand a C. And he would simply not accept a C in Spanish. That was basically like getting an F. And when Papi didn’t understand, he grew quieter and more serious than usual. Mami called it being stoic. Lola called it something else.

Being the reason for his silence was mortifying.

Mami was the one who yelled. She had a knack for seeing each of her childen’s shortcomings as yet another opportunity to remind them about the sacrifices she and their father had made, and continued to make, so that Lola and her younger brother could one day go to college—and this speech always lumped them into a single unit for some reason, even though they were two grades apart. It was together or nothing. Never mind the fact that they had different friends and liked different subjects (Lola: everything but PE and, okay, Spanish; Tommy: PE and lunch) and that Mami’s disappointment in Tommy evaporated much more quickly than when Lola was its cause. She could hear her mother’s voice growing increasingly melodramatic in her head: “Hacemos todo en esta vida juntos, o no lo hacemos.”

The last time Lola had gotten a bad grade, it hadn’t even been that bad, comparatively—a B- on a ninth-grade chemistry test in which the class average had been a crushingly low C. She came home prepared with that information, but her parents didn’t care. Everyone else’s grade should have been yet another reason for her to excel, her mother had told her. As for her father—well, he barely talked to her for a week, which was a worse punishment than being grounded given that Lola had nowhere to go anyway.

There was no way her parents hadn’t already seen her grades—they would have gotten the same email she had, and Papi would have likely opened it instantly, too. She looked at the clock: 2:35 p.m. That meant she had approximately three hours and twenty-five minutes before she was tasked with defending herself, a one-girl stand-in for all of their hopes and dreams.

It wasn’t as if Lola hadn’t tried to get an A. She had put extra effort into her Spanish study guide—it had the most highlights, the most notations, and the most scratched-out attempts at sentence diagramming of any of her notebooks, and it was also the most dog-eared and flipped-through of all her guides.

And that was saying something, given how the only thing she ever did was study when she wasn’t helping Tommy with his homework, or helping around the house so Mami didn’t have to do more work, or sneaking a few minutes on YouTube before she dove back into another flashcard session. Other kids had sports or an after-school job. Lola had school.

Maybe that was for the best, because she spent so much time being the good daughter, the one Letty and Thomas Espinoza didn’t have to worry about, that she had little time for anything else, even though an extracurricular or two would look good on her college applications. Hopefully, studying alone would be the key to a college acceptance letter and a scholarship rolled into one. Still, the pressure to succeed sometimes felt more like a burden than the opportunity her parents promised it was.

A ball of dread settled in Lola’s stomach. A C in Spanish would mean consequences.

Lola’s hand slipped from where it was propping her chin up, knocking her back to reality. She checked her phone’s front-facing camera to make sure the lipstick she’d worn that day, a matte taupe-y liquid formula that would probably survive the apocalypse, hadn’t smeared over her cheeks. It was still firmly in place—at least she had that going for her.

“You okay?” Ana whispered, which was ridiculous because Ana was loud in general and always louder than normal precisely when she was trying to be quiet.

“Yeah, sure,” Lola said.

Sometimes things weren’t worth explaining, especially to people who didn’t get it. Even best friends.

Ana and her parents were decidedly more chill about her grades than Lola or her parents had ever been about hers. Ana was smart, too, but she didn’t get straight A’s, and she let B’s and the occasional C roll off her like it was nothing. And not only were the teachers generally kinder to the athletes, but Ana was constantly finding loopholes that allowed her to coast. When they entered high school and signed up for the same Intro to Spanish class together, no one ever checked whether Ana was already fluent and could have skipped straight ahead to the college-extension course.

(She was and she could’ve, courtesy of a mother who could trace her family lineage in Texas back twelve generations. But the teachers hadn’t bothered to test Ana’s knowledge of the subjunctive.)

Lola sighed again, a little too loudly.

“Miss Espinoza, Miss Morris, is there something you’d like to share with the rest of us?” Mr. Wesley asked.

Lola shook her head quickly. Mr. Wesley didn’t expect anyone to actually answer him. He demanded silence.

Ana began focusing even more intensely on the oracle deck, which she’d been shuffling under the table. Her interest in such things had been sudden but sincere, and she liked to attribute the things their classmates did to the different planet placements in their birth charts. Lola was skeptical, which Ana said was typical for a double Sagittarius.

When the bell rang, Ana bolted upright and helped Lola pack up her things.

“So, party?” Ana asked again as they walked outside to the parking lot together. “You in, Lo?”

She was not letting Padilla’s note go.

Lola sighed. “I got a C in Spanish, A. They’re not going to let me go to a party after that. I’m telling you, when my dad finds out, it’s going to be bad.”

“What’s going to be bad?” Tommy was leaning against Lola’s car, trying to approximate as cool and disaffected a look as he could. Her brother was a lot of things; subtle was not one of them. “’Sup, Susana?”

The Espinoza children had the same warm brown eyes and tan skin, and that was where their similarities ended. Fifteen-year-old Tommy was frenetic, excitable, quick with comebacks. His favorite thing in the world was roasting someone, but he had a particular knack for delivering his punch lines as a form of endearment. Lola, meanwhile, was more deliberate, perpetually stuck in her own head, weighing options before each next step. It was nice in her head, mostly. She could think through problems completely. She could plan.

“Your sister,” Ana began dramatically, “has gotten a C in Spanish and is using that as an excuse to skip Padilla’s party tonight. I can’t believe my best friend is such a Sag.”

“Okay, but . . . when was the last time Lola went to a party?” Tommy shot back, almost as if Lola wasn’t both standing five feet away and his ride home.

She exhaled to remind him of her presence. Her brother laughed and reoriented himself to what was obviously the bigger issue.

“Yo, really? Lola, you got a C in Spanish? Spanish?! Mami’s gonna kill you.”

Lola felt her face getting red under her foundation. “I know. Just . . . get in the car, Tommy, please.”

“Hey, if it helps, you can always tell Letty about the time señora Smith knocked ten points off my midterm freshman year because I refused to call a chamarra ‘chaqueta,’” Ana offered helpfully. “It’s not either of our faults they insist on teaching, you know, Spanish Spanish.”

Lola said goodbye to Ana, promised to text her, also promised again to maybe at least think about the party (even if a promise was only a promise if you weren’t halfway lying about it), and got into the hand-me-down Prius Papi and Mami had given her when she turned sixteen. It was quiet and unassuming, and though Lola had driven it for a year and a half, even she had trouble picking it out of the hundred other Priuses in any grocery store parking lot. In a lot of ways, it was Lola in car form.

She sat in the front seat for a minute as Tommy played with the aux cord, cycling through playlists until he found one he liked.

“For real, though?” he tried again. “In Spanish? Man, even I’m getting an A in Spanish. And señora Smith once called me a human dolor de cabeza. That’s a headache, Lorenita. In case you need me to provide you with a traducción.”

“Tomás, can we not?” Lola asked quietly, almost pleading. He scowled at his full name but got the hint.

Lola started the car, and together they rode toward home—Tommy to his dinner, Lola to her doom.