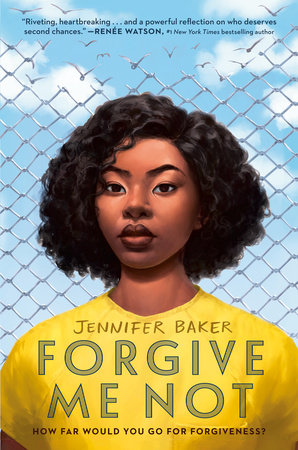

Forgive Me Not

Hardcover

$19.99

- Pages: 400 Pages

- Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

- Imprint: Nancy Paulsen Books

- ISBN: 9780593406847

An Excerpt From

Forgive Me Not

I was always good at taking notes in school. Only this time it’s my life, not a quiz. I want to make sure I remember everything she tells us. Apparently, I’m the only one writing all this down. The girl sitting up front and Serena stare ahead, waiting for this to be over.

This room is pretty tight for instruction, not like Claremont High School, where desks are spaced out and the walls are painted beige so it feels roomier. Here, three wide bookcases line dull green walls and block all except for a sliver of the windows. Tattered textbooks and donated paperbacks, some worn and some in pretty good condition, fill the shelves, along with student workbooks. Our school notebooks are stacked based on the group we’re in. Detention holds two sets of classes Monday through Friday, where our instructor stuffs math, history, composition, and earth science into three and a half hours. Serena is part of the morning group, from nine to twelve thirty, before lunch. I’m in the afternoon batch with Petra and Eve, from one thirty to five, before dinner, at six.

If I thought the moldy smell was a lot in my dorm, it’s nothing compared to how musty this room is. A ceiling fan barely circulates the air, plus the lone radiator near the door is covered in cobwebs; every so often it clangs to signal its attempt to work. I rarely feel any heat in class, so I make sure to wear a thicker undershirt beneath my jumpsuit. We sit at slim, unsteady picnic tables and on dusty fold-out chairs. There are four rows with three tables, each with scratches, markings, and old gum decorating them. During class, all the seats are filled, but today the three of us are spread out. The table I’m at jiggles when you lean on it. After it threatens to tilt over one too many times, I stuff a folded page from my notebook under a leg.

Counselor Susan raises her voice in an attempt to make her presentation interesting. With a laser pointer in hand, she moves from one side of the board to the other, letting the dot emphasize what she’s saying. She seems nervous. She keeps tugging at her pencil skirt or the edge of her black blazer when she talks. I’m not a fan of public speaking either. Yet another strike against me whenever I’m compared to my older brother. The world is Vin’s stage, for track, for debate, for lacrosse. You name it. But Counselor Susan’s cheeks flush when she stumbles or when she clicks on the computer to move the slide forward but it goes backward. It reminds me of how much I fidget when called up to read a report in class or when I had to be onstage for more than a second to pick up a certificate. Her fear makes her more real and less like an authority figure.

Serena sits at the end of my row and raises her hand a few minutes in. I try not to stare at her. The lilac tattoo peeking out from under her jumpsuit top always catches my eye. How bright the purple and white flowers are on her freckled skin. She’s chewing gum, a luxury in here, and each smack punctuates her question. “Sooo what you’re saying is this all started because someone killed a kid by accident? That’s why I gotta deal with this bullcrap?”

“Well,” Counselor Susan begins, “yes and no. It started with an understanding that something more needed to happen to encourage a decline in recidivism for offending youths.”

“Resida-what?” the girl in the front row, biting her nails, asks. From the traces of blood I see on her pale fingers, she’s chewing them raw.

“Recidivism,” my counselor says. “It means repeat offenses. We want to limit that.”

An index finger in her mouth, the girl is a little hard to understand when she responds, “So why not just say ‘repeat offenses,’ then?”

“How about I get through this and then you can ask questions, all right?” Counselor Susan smiles so wide it takes up her whole face.

Counselor Susan brings up a slide with a timeline of the history. The Trials started twenty-five years ago because a seven-year-old Black girl was killed by her thirteen-year-old cousin when he wrestled with her. I almost drop my pencil and have to hold back a sob hearing how a kid younger than me also hurt someone in his family. And my sister is, was, seven too.

The boy’s name is LeVaughn Harrison. Even at his age, he was considered developmentally sound enough to understand what he did was wrong, and a grand jury decided he should be tried for murder. This caused an uproar. Some argued he hadn’t been vindictive, that it was an accident, while others insisted the girl’s medical examination revealed injuries worse than an accident would account for. A year after her death, when LeVaughn was fourteen, a jury sentenced him to life in prison.

My counselor clicks to images from news clippings. The side-by-side photos of LeVaughn and his cousin are black-and-white photocopies, making their skin even darker, so some of their features are hidden. But I can still see how young they are. The seven-year-old girl has four puffy braids sticking up from her head. Her eyes are dark orbs staring straight ahead. The boy has pouty lips and his nose is a rounded nub at the end, like mine and my mom’s. The photos feel like mug shots. They don’t look like children; they look like ghosts.

My counselor plays a one-minute video of people encouraging government officials to take cases like this more seriously.

In the video, a woman dressed as professionally as Counselor Susan leans into a microphone. “Reform needs to happen,” she says. “Real reform. How do we know a kid at this age can understand the repercussions of their actions when sent to prison for murder? Studies show . . .” And so on and so on. Appeals were made by the boy’s family members all the way up to federal courts. The boy’s life sentence held, but people in office agreed something needed to change.

Per Counselor Susan, “When an investigation was conducted by the Federal Department of Corrections in conjunction with the Bureau of Detention Services, they saw how much money was spent simply to house inmates for years on end, on top of all the time spent in courts. All this was brought to Congress, who helped create this new form of juvenile justice nationwide.”

“Is that how most decisions are made in this country?” Serena asks.

Counselor Susan doesn’t answer. She goes to the next slide, with a list titled CONSIDERATIONS. I scribble this down too.

Before the Trials, she says, many juveniles couldn’t afford legal representation and got assigned public defenders or dealt with bias in the court system, especially Black and Brown kids. Serena and I glance at each other in recognition of what’s been obvious from the moment we got here. I’ve noticed how many more girls who are inmates look like me, compared to how many guards and counselors look like Counselor Susan and dictate our every move.

Counselor Susan tells us that juvenile reform programs weren’t given enough funding to survive or work on a wider scale. There were no guarantees that repeat offenses wouldn’t happen. And at the same time, there was the question of how juvenile inmates could support the economy. Trials were developed as a way to try and respond to these needs.

“The goals are less kids on the street doing harm, so they don’t grow into adults who cause harm.”

Serena pops a small bubble before asking, “Okay, so where do the victims come into play?” Her arms are crossed. She looks skeptical and I can’t blame her. This is a lot of information. I’ve filled up two pages with history, considerations, LeVaughn and his cousin, speeches for and against how LeVaughn would live his life. Mostly, it sounds like adults pushing what they think we need to hear, rather than talking to us.

“I’m glad you asked, Serena.” Her next slide says VICTIMS at the very top. “Think of what we do now as similar to a court but not. Say the victim is pressing charges against you, the offender.”

“Thanks for that,” Serena says.

“Sorry. An offender. The victim decides to press charges, and you—I mean, the offender—is taken into custody.” The red dot circles the word CUSTODY. “Then a judicator serves as a kind of liaison assisting the victims, helping them understand what options are available to them. That means three choices.” Counselor Susan uses the laser to underline TRIALS, CONFINEMENT, FORGIVENESS. “From there, the victims make a decision on what fits the situation, and then you—I’m so sorry, I mean, the offender—is sentenced to one of those three options.

“For confinement, the judicator and the Bureau will decide a fitting time at a long-term facility, and will work with the victims to ensure that’s acceptable based on the offense. In the case of Trials, the victims pick the category, there are several. However, I won’t be getting into all that. Then a judicator, with the help of the Bureau, creates the Trial in conjunction with the victims, based on the category and the offense. Us counselors could be considered your defense team, because we’re here for you. The victims make all decisions alongside their assigned judicator. This includes how your Trials are measured.”

“Do people ever get forgiven?”

The red dot lands on the nail biter’s face. “All the time!” Counselor Susan says a little too enthusiastically. Petra is the only person I know who’s been forgiven, yet that wasn’t from the start. It was a hard-won forgiveness.

“Speaking of forgiveness.” The board gleams with SO YOU’VE BEEN FORGIVEN, along with a yellow smiley face. “This is the good news for you. As I said, forgiveness happens all the time. Your Trials are pass or fail, and it depends on how many you have. It could be one.” She holds up a finger to illustrate, as if we can’t count single digits. “Or it could be several. Your job is to show your dedication to forgiveness.”

“Forgiveness” is the biggest word on my page. It’s in all caps and I underline it twice. I linger on the word and the possibility. It’s not impossible. Petra said so. This is what I’ll have to cling to. And maybe Counselor Susan can help me make this a reality.

“Yeah, okay, but how brutal are the Trials?” Serena chimes in.

“Girls, that’s not what this is about. The Trials aren’t meant to be brutal at all. Remember that being here”—my counselor’s pointer stops on each wall to the ceiling to the whiteboard behind her—“is not about incarceration; it’s about rehabilitation, a reset. Consider the Trials a do-over.

“Crimes have been committed. And comprehension of why these things happened as well as ensuring no offenses happen again is the goal here. And with that—” A pie chart fills the whiteboard: 89 percent success rate in reducing juvenile recidivism throughout the country since the initiation of the Trials. This stat brings a grin to my counselor’s face that isn’t forced, the whole front row of her teeth show and they’re as white as her blouse. Another adjustment of her blazer, and she says she’s done.

“Any other questions?”

A pop of gum and a raised hand signal Serena’s latest question. “Sooo, what happens if you don’t finish the Trial. Like . . .” Serena chews before finishing as if this helps her think. It’s just like the click click click of my counselor’s pens whenever she pauses before answering during our meetings. “Like if you quit the Trial. Then what?”

The upper half of Counselor Susan’s body does a little shake before she points at Serena, almost like she’s won a prize. “I’m so glad you asked that!”

We wait for a new slide, but Counselor Susan doesn’t click for one. The laser pointer doesn’t highlight something else we need to know beyond the success statistics lit up in front of us.

“Quitting a Trial means the victims, along with their judicator, decide if they’d like to forgive you regardless and expunge any record of your crime after a short probation. Or pursue confinement. Unfortunately, confinement means—”

I rest my golf pencil and repeat Petra’s words from yesterday to myself: You have a criminal record.

My nail digs at a leftover patch of old gum. Probably one from Serena from another day. “What happened to the little boy?” I ask.

“What little boy, Violetta?”

“LeVaughn. The one who started all this.” It’s hard to believe a seven-year-old girl’s death forced a whole new way of “justice.” I know kids have helped initiate change before. But this boy was only two years younger than me. By now, he’s a grown man. Does he get to live out his life like normal, or as normal as life could be after you’ve killed someone? Did his family ever forgive him for roughhousing, or is he still sentenced in prison? What I really want to know is: Is he okay?

“I’m sorry to say he died.”

Serena whistles. “Damn, that’s a sinister mic drop.”

I almost pound the table. “Died! Of what?”

“I don’t know. He passed away about twenty years ago. I believe he was eighteen at the time.”

Shutting off the projector, Counselor Susan stands a bit more confidently, with her thin arms at her sides, or maybe she’s just relieved to be done. The red glow of her laser pen disappears when she announces, “Ladies, your respective Trials will be during the time you usually have free. And you’ll still have to attend class in preparation for testing in June.” Counselor Susan almost scolds us with a wag of her finger. “Just because you have Trials doesn’t mean you don’t get an education. It’s incredibly important.”

Picking up the nub of my pencil, I circle LeVaughn’s name over and over. I have to find out what happened to him. I just have to.

The Trials were born as an option. I know my sister’s death is my fault. There’s no arguing that. The question is: What comes next? Because she’s not here, my family gets to decide. And they’ve decided I need to be reformed.