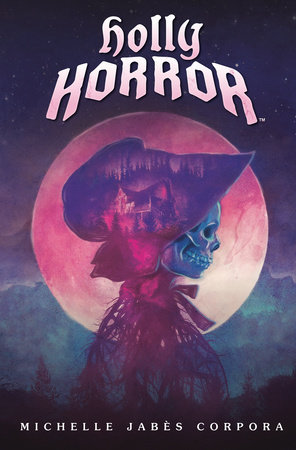

Holly Horror: The Longest Night #2

Part of: Holly Horror

- Pages: 352 Pages

- Series: Holly Horror

- Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

- Imprint: Penguin Workshop

- ISBN: 9780593523568

An Excerpt From

Holly Horror: The Longest Night #2

“Evie? Are you there?”

Evie Archer blinked. The voice on the phone was muted and distant, as if someone were calling to her while she was lying at the bottom of a swimming pool. It was peaceful down there, in the daydreaming. Quiet. There were no thoughts, no painful memories. There was nothing at all. And that was just fine.

She didn’t want to return to the surface, but she knew she had to.

Evie rubbed her eyes, dragging herself back into the present moment. She was sitting in the wicker fan-back chair in her bedroom, with Schrödinger purring in her lap. Around her, Hobbie House groaned and creaked like it always did when the cold New England wind blew over the Berkshires. She pulled her patchwork quilt more tightly around her shoulders and readjusted the phone against her cheek. “Yeah, Tina, I’m here,” she replied. “Sorry, I just spaced out for a minute.”

“You need sleep,” Tina said with a sigh.

“You sound like my mother,” Evie said wryly. She had only known Tina Sánchez for about two months—they’d met on Evie’s first night in Ravenglass—but she already felt closer to the police chief’s daughter than she had to almost any of her friends back in New York. After all, she’d shared things with Tina that she’d never told anyone else. And Tina was there for her when . . . Evie grimaced, wishing she was back at the bottom of that pool.

“It’s late,” Tina went on. “C’mon. We can go over this stuff again tomorrow.”

Evie clenched her fist until her fingernails bit into her palm. Schrödinger shifted and the purring stopped, as if he could sense the tension suddenly pouring off her in waves. “No, no,” she said. “I want to do it now.”

“Evie, you’ve got to stop blaming yourself for—”

“Please, Tina. Now.”

It had been two weeks since that ill-fated homecoming night. Two weeks since Evie had fallen into the land of shadows, since she and her brother, Stan, had emerged from the gold mines unscathed. Two weeks since Desmond had gone in and never come out.

Sleep and peaceful daydreams weren’t going to bring him back. She had to focus. Concentrate. Remember. No matter how much it hurt.

There had been a great deal of confusion the day after homecoming—at first, no one was even sure that Desmond had gone into the mines at all. Friends at the dance had heard him say he was heading there, but no one had actually seen him go in. People held out hope that he’d taken a fall in the woods, that his phone had run out of batteries, that he would come limping home the next day, feeling sheepish. Search parties had scoured the woods up on the mountain and the mine tunnels for two days straight, and if it hadn’t been for Mom putting her foot down, Evie would have joined them. Then, at the end of the second day, they’d found a boutonniere. A cream white lily, wound with a stillfresh spray of baby’s breath. It had been lying near the mouth of a mine shaft, hundreds of feet deep.

The news article in the Pittsfield Post described Chief of Police Victor Sánchez presenting the boutonniere to the victim’s parents and getting confirmation that the item did indeed belong to their son, Desmond King. There hadn’t been any further details, but Evie had imagined the scene in her head dozens of times. Chief Sánchez walking toward them, his face a mask of sorrow. Mr. King seeing the flower in the chief’s hand and falling to his knees. Mrs. King clutching a framed photograph of Desmond in her arms and crying out—No, not him, not my baby . . .

The nightmares she’d had when she’d first moved to Western Mass—the ones of Holly Hobbie, the Lost Girl of Ravenglass—stopped the day she faced down the darkness in the mines. But these new horrors, they didn’t come to her in dreams. They came in every waking moment she had to live with the knowledge that Desmond—beautiful, wonderful Desmond—might be dead because of her.

The only thing she’d had to hold on to those past two weeks was the packet of papers she’d found underneath a loose board in her bedroom closet. Papers that Holly told Evie to find when they met down in the Shadow Land. She’d been calling it that since she got back home, capitalizing it in her mind, giving a name to the place that was nowhere and everywhere at once. You can find my notes, Holly had said, now that I remember where I left them. About Sarah. About . . . everything. Maybe you can finish what I started. Evie knew now that her cousin Holly had been investigating the nineteenthcentury disappearance of Sarah Flower, known by locals as the Patchwork Girl, right before she herself went missing from Hobbie House. With a shiver, Evie remembered something else Holly had said right before letting her go.

Sarah and I, we’re not the only ones down here.

Whatever else lived in that terrible place might have taken Desmond. And Evie was convinced that the answer to finding him lay somewhere within Holly’s notes about Sarah Flower, and the history of Ravenglass.

“Okay, okay,” Tina said. “We’ll go through it. But quickly—I have school in the morning.” She paused. “Speaking of school . . . When, um, when do you think you’ll come back?”

Now it was Evie’s turn to sigh. The thought of walking through the halls of Ravenglass High, and the stares and whispers that would inevitably follow, filled her with a special kind of dread. She glanced out the window, where she could still see the muddy tire tracks and footprints left behind by TV crews, news reporters, and social media influencers looking to get a peek at the infamous Ravenglass “Horror House,” which had reemerged into the limelight after forty years’ slumber. It was already a good story when people realized that Evie had vanished on the anniversary of Holly Hobbie’s disappearance from the house in 1982. When they found out that Desmond had been Evie’s date to the dance and was now missing himself—the story only got juicier. There’d been good reason for Evie holing up at home for the first few days, but it had been a week since the last reporter had come sniffing around, so her excuses for skipping school had started to lose their potency.

Still . . .

“I’m not sure,” Evie murmured. “Soon, I guess.” She didn’t give Tina time to press her further. “Anyway, let me get over to the closet.” She stood up, lifting the big orange cat off her lap and placing him on the bed. Schrödinger grumbled, stretched, and gave her one last, sustained glare before sauntering out of the room. Off to go mole hunting, Evie guessed. Grasping the old brass doorknob, she opened the closet and adjusted her bedside lamp to illuminate the papers taped on the inside of the door. There were photographs, handwritten letters, and papers of all kinds—old and yellowed and faded with age. Evie was sure they’d have been in even worse shape had Holly not stored them in a cool, dark place all those years ago. Each of the items, in one way or another, had something to do with Sarah Flower and her family, who’d lived in Hobbie House when it was first built in the mid-1800s. It was everything that was left of the little girl. Except this, Evie thought, touching the gold locket at her throat. It had been Sarah’s, and then Holly’s. Now it was hers.

“So,” she began, her fingers on the locket, “in 1851, Sarah Elizabeth Flower is born to parents William and Mary Flower. Mrs. Flower dies in childbirth, leaving Mr. Flower to raise Sarah on his own. He’s a wellrespected man in the community, so when Wallace Brand comes to town looking to mine for gold, he hires Mr. Flower to be his foreman. Things seem to be going fine until Mr. Flower’s sudden death some years later. They find his body in the cellar of Hobbie House, and Sarah is blamed. She goes missing around the same time, and neither appear in any records after that. Work in the mines tapers off at that point as well. The house and land lay vacant for years, then it changed hands several times, but it was rarely lived in for long—until the Hobbies bought and renovated the place sometime in the 1970s. Does that sound right so far?” A moment of silence passed. Evie pressed the phone closer to her ear. “Tina?”

“No, that’s right,” Tina said. “I just . . . Look, Evie, I believe you, okay? When you told me about Holly, and this shadow place, and everything else—I believed you then, and I believe you now. I’m just not sure this is a healthy way to process what happened to Desmond. Maybe there are answers to be found in these old papers, and you know my little writer’s heart can’t resist a good story. But I think you also have to open yourself up to the possibility that Desmond is . . . well, that he’s—”

“You know what,” Evie blurted, cutting her off. “Maybe you’re right. Maybe we should call it a night.”

Another beat. “Yeah,” Tina whispered.

Silence filled the line between them.

“Hey, so . . . is everything okay with you?” Evie asked after a moment. She realized what a selfish friend she’d been over the past couple of weeks, since they’d first met. Sure, Tina had been much more interested in poking her nose into Evie’s business than talking about herself, but Evie hadn’t done much to counter that. Other than knowing her dad as the police chief, Evie knew next to nothing about Tina’s life. Recently she’d found out that Tina had an older brother in college—Carlos—and a younger brother named Danny who was in second grade at Ravenglass Elementary, but that was it.

“Oh, me?” Tina said, sounding a little surprised. “I mean, sure. My tito and tati are flying in from Puerto Rico tomorrow, and Mom has been cleaning the house for six days straight, so there’s that.”

“That’s nice.”

“I guess.”

Evie quirked an eyebrow at Tina’s sarcastic tone. “Don’t you get along with your grandparents?”

“They’re staying until New Year’s,” Tina said flatly. “People complain about having to spend time with their families for a week. Imagine what it’s like to have them around for two months!”

Evie got the feeling that there was more to it than that, but decided not to question her further. It was late, and clearly there were things neither of them wanted to talk about. “I get it,” she said instead. “Talk to you tomorrow, then?”

“Tomorrow,” Tina agreed, sounding relieved. “Nightnight, Farmgirl.”

“Night, Tina.”

Evie ended the call and tossed her phone on the bed. She sat down next to it and rewrapped herself in the patchwork quilt like a burrito. It was after midnight, and although Evie felt tired, she knew she wouldn’t be able to sleep. She decided to go to the attic.

When she first moved into Hobbie House, everything about it seemed sinister. A Pandora’s box of chaos that once opened, couldn’t be closed again. Back in New York, Evie thought things couldn’t get any worse than they were after her parents got divorced, but when the gift of a rentfree house turned out to be a curse, she soon found out how wrong she really was. But ever since the events of homecoming night, the house felt different. Warmer. No longer her adversary, it had shared its secrets with her, and she had done the same. They understood each other, Evie and the house. She feared it no longer. It was what lay beyond the walls of Hobbie House that frightened her now.

Which was why Evie found herself pulling down the stepladder to the attic in the middle of the night, while her mother and brother were fast asleep in their beds. Just a month ago, going up to the attic—even during the day—terrified her. But for the past two weeks, she had gone up there almost every night, taking an electric candle along to light her way. It was comforting, somehow. But that wasn’t the only reason. She went to the attic on the off chance that someone would be waiting there to meet her.

At the top of the ladder, she set down the electric candle and reached for the little pull chain, turning on the single bare bulb that hung from the rafters. That done, she climbed up, dragging the patchwork quilt with her.

The attic didn’t look quite as old and forgotten as it had when they’d first arrived. Mom and her broom had eventually made their way up there to sweep away the dust and dead spiders, and replace them with neat piles of clearly labeled storage boxes full of holiday bricabrac and old souvenirs. Still, she hadn’t removed most of the Hobbies’ old things they’d left behind, including Holly’s steamer trunk. Evie opened it up, smelling the cloud of rosescented air that wafted up from within. She ran her fingers along Holly’s things—the old dolls, the dress with pearl buttons, the stained white scarf with lace along the edges. The blue bonnet, the thing that had started it all, lay on top, its blue ribbons curled up into itself like a sleeping cat. Evie thought it had belonged to Holly when she first found it, but her sense of it being a lot older than forty years had been correct. Like the locket, it had once belonged to Sarah Flower. All three of them, Sarah, Holly, and now Evie herself, were connected—not only by the house, but by something else, too.

Whatever it was, it wasn’t finished yet.

With shaking fingers, Evie did the same thing she’d been doing almost every night since Desmond had disappeared. She pulled the bonnet onto her head, tying the ribbons under her chin in a bow. Then, wrapped in her quilt, she turned to the white fulllength mirror and stared at her reflection, praying that someone else’s face might be looking back at her.

“Where are you, Holly?” Evie whispered. “Why won’t you talk to me?”

She stared into the mirror. Underneath the bonnet, her long, copper-colored hair was lank and unwashed. There were dark circles under her eyes, making the spray of freckles across her face look muddled. The awful red rash on her right cheek, which had been a constant reminder of what had happened homecoming day, had finally faded, leaving nothing but a dry area where it had once been. Sometimes it still felt like it was there, though—the pain hovering over her skin like a ghost.

“First, you won’t leave me alone,” she went on. “You take over my life, you haunt my dreams, you make me feel like I’m losing my mind—and now? Now that everything is so messed up, now that I need you, you just . . .” Her voice had risen to an angry, ragged rasp. Her eyes were stinging, her nose starting to run. She sniffed and wiped her face with her forearm. She glared back at herself in the mirror, pressing one hand against the cool glass, hating both what she saw and what she didn’t see.

“Talk to me!” she cried.

But just like every other night, there was no answer.

Meanwhile . . .

Jack Míng Chen lay on his belly on the living room floor, watching his favorite TV show. He was wearing his favorite footed pajamas, the blue ones with teeth along the hood that made him look like a shark. They’d been a gift for his seventh birthday the year before, and they were almost too small now. But Jack was going to wear them for as long as he could. His best friend Danny had the same pair, and whenever Danny came over for a sleepover, they’d both wear the pajamas and slither around on the hardwood floors, pretending to be on the hunt.

“Five more minutes, Jack!” his mom called from the kitchen. “Then it’s toothbrushing and bedtime, okay?”

“Okaaay . . . ,” Jack moaned. Five minutes was not enough time to finish his favorite episode, but usually when his mom said “five minutes,” she really meant fifteen, so he wasn’t too worried. What was worse was the racket his parents were making, running the sink, clattering forks and dishes, trying to soothe his mewling baby sister, and worst of all—talking.

“Elena Sánchez told me this morning at the bus stop that Victor called off the search for that boy from RHS—the Kings’ son?” his mother was saying.

“Not surprising,” his dad replied as the baby whined and burbled. “It’s been a couple weeks, hasn’t it? They probably only kept it going this long for the parents’ sake.”

Jack’s mom tutted. “It’s just awful. I’ve always said those mines are dangerous. I’ve told Victor, more than once, that they should have that place sealed off with concrete. Maybe now they will.”

The mines up on the mountain were forbidden territory for both Jack and Danny, but that didn’t stop the boys from riding their bikes up there as often as they could. Edgewood’s wooded paths made it easy to get through the neighborhood and reach the mountain road unseen. They liked playing at being explorers near the ominous black mouth of the mine entrance, pretending to find gold buried in the dirt. They’d make up stories about the ghosts that lived down there, and often imagined going inside and finding a skeleton—dry flesh hanging in rags from its bones, a treasure map gripped in its cold, dead hand. They were too scared to actually go inside, but they’d dare each other to see who could get closer, until one of them poked the toe of their sneaker past the threshold. Then they’d leap onto their bikes, whooping, and pedal like crazy all the way home.

Jack imagined that high schooler lying somewhere in the darkness, in the silence, decaying just a little bit more each day. I guess there really will be a skeleton down there now, he thought with a shiver. To drown out those unwelcome thoughts, he turned up the volume on the TV, stuck one of the shark head’s felt teeth into his mouth, and focused on the show.

It was a show about four kids who had to solve mysteries with the help of someone named “the Puzzlemaster,” who sent them clues through coded messages they found all around town. Jack had already seen every episode, twice, but he didn’t care that he already knew all the answers to the puzzles. For instance, in the part he was watching, he knew that three of the kids would find a hidden message inside a book at the school library, but wouldn’t be able to figure out what it meant until the fourth kid arrived and told them, because of something she had learned in history class. Jack watched eagerly, sucking on the shark tooth, as one boy pulled the book off the shelf and looked amazed as it magically opened to one special page—

A flash of movement from the window startled him. Jack dropped the sodden fabric from his mouth and looked up. It was almost as if a shadow had walked past, shutting off the moonlight just for a moment. But there was nothing there. Jack thought maybe it was the neighbor’s cat out on the prowl again. It often liked to lurk in the Chens’ backyard, killing birds. Jack remembered just a few weeks ago, when he’d found the dead finch out on the patio. Its small, soft body torn, its yellow feathers sticky with blood. No matter how much his mom sprayed the patio with cleanser, the stain left behind just wouldn’t wash away.

Shrugging, Jack watched his parents take the baby up to bed, and estimated he had at least another ten minutes before they came for him. He refocused on the show. The three kids were crowded around the book, perplexed by the puzzle inside it.

“Maybe it has something to do with the page numbers?” one kid guessed.

Wrong, Jack thought.

“What if we’re supposed to read every other word?” said another.

Wrong again, Jack thought. It made him feel smug, knowing more than those dumb kids. If the Puzzlemaster had chosen him instead, he’d have been able to figure out the clues on the first try. That was a fact.

“Come on, you guys!” the first kid cried. “We’ve got to solve this before time runs out! Ticktock!”

Now the door to the library opens, and the last kid comes in, Jack thought. He stared at the door in the background, waiting.

The door swung open, slowly. A beat passed. The three kids in the foreground continued to study the book.

Jack cocked his head and scooched closer to the TV. Was it frozen? No, the three kids were moving. Breathing. Why wasn’t the fourth kid coming through the door like she was supposed to?

But there was something coming through the door. Something dark, like a shadow. It crept into the brightness of the scene, along the carpeted floor, the walls, the bookshelves lining the background. The three kids didn’t seem to notice it at all.

But Jack noticed. “This isn’t right,” he muttered to himself. “This isn’t how it’s supposed to happen . . .” He picked up the remote control from the floor and pushed the stop button, but the show kept playing. He smashed the power button with his thumb, but the TV stayed on.

On the screen, the shadow was coming closer, rolling over the shoulders of the kids, over their fingers touching the book, and then the book itself. They just stared silently, still perplexed by the puzzle, still living in the moment as if nothing was wrong.

“Mommy . . . ?” Jack said. He tried to shout, but his voice was as soft as feathers. He tried to sit up, tried to move away from the screen, but found that he couldn’t. Like the kids in the show, all he could do was remain just as he was. Looking, and breathing.

“Almost time for bed, Jack!” his mother called from upstairs.

Jack whimpered. But she was too far away to hear him.

And then the darkness reached the screen, and Jack felt relief that it could not pass through that barrier, that somehow the logic of the world would keep it inside.

But in the moment it took for Jack to take his next breath, the black thing had reached through the screen, pressed past it like a hand through water, and reached out toward him.

Before he could loose a scream, it filled his eyes and his mouth with a great, dark silence.

A moment later, the show continued. Jack lay on the floor, just as if nothing had happened. He stared at the TV with dark, unblinking eyes, his slippered feet kicking back and forth in a clockwork motion.

Tick.

Tock.

Tick.

Tock.

On the show, a happy, smiling girl entered the scene, bringing answers to a puzzle yet unsolved.

2

Evie sat on a squashy green couch in her aunt Martha’s second-floor apartment, a steaming mug of cinnamon tea warming her hands. Outside the front window, white flurries whirled over Main Street, making Ravenglass look as quaint and lovely as a town in a snow globe. Thanksgiving was still three weeks away, but the businesses and restaurants were already gearing up for the holiday season, and the streets were busy with tourists from all over who’d come to enjoy a little slice of Americana.

Evie watched them walk by—cheeks pink with the cold, arms heavy with shopping bags—and wondered what it must feel like to be so carefree.

“Gingersnap?” Aunt Martha said, offering a plate of spice-scented cookies.

“No, thanks,” Evie replied, and sipped her tea.

Aunt Martha’s shoulders sagged. She set the plate on the coffee table and lowered herself into an armchair. She wore smoke-gray leggings and a medallion-print tunic in shades of blue. Her long silver hair was loose, and she gathered it into a ponytail before reaching for her own mug of tea and a cookie. “So,” she said, taking a small bite of a gingersnap. “How’s your mom doing? I haven’t talked to her in a few days.”

Evie shrugged. “She’s all right, I guess. She’s been trying to be home earlier in the evenings, but with the holidays coming up, the inn has been busier than ever.” Mom’s job at the Blue River Inn seemed to be growing in responsibilities by the day—she’d only worked there for a month or so, but she’d already made herself indispensable. Normally, Mom’s workaholic ways irritated Evie, but things had been better between them lately. Not perfect, but better. Evie knew she wasn’t staying at work to avoid being home anymore, she was just busy. And that was okay. Evie wanted to be alone, anyway.

Aunt Martha nodded, chewing. “And Stan? How’s his ankle?”

“Healing,” Evie replied. “Dr. Rockwell says because of the kind of fracture it is, he’ll have to be non–weight bearing for four more weeks. So he’s annoyed, of course. But at least now he’s gotten used to the crutch.”

“Well,” Aunt Martha said, tucking her bare feet under her. “It could have been a lot worse.”

Evie thought about how close she and Stan had come to not getting out of the mines at all. How close they had come to dying down there in the darkness. “Yeah,” she said softly. “It could have.” She tried to ignore the unspoken words, the ones that hung in the air between them.

You could have ended up like Desmond.

She took another long swallow of her tea, hoping it would dispel the chill from her body.

It didn’t.

Aunt Martha finished her cookie, and was toying with the heavy silver chains she wore around her neck while watching the passersby outside the window. “I just love this time of year, don’t you?” she said with a smile.

“I didn’t realize you were a big Christmas person.”

“Oh, I’m not,” Aunt Martha said. “People forget that before Christmas even existed, this time of year was special because of the winter solstice.”

“The solstice,” Evie mused. “Isn’t that the shortest day of the year?”

“Yes,” Aunt Martha said. “And the longest night.”

Evie drained the rest of her cup and set it down on the table. “It doesn’t sound like much fun to me.”

“I guess it’s not very fun,” Aunt Martha admitted. “But it is very meaningful. People have been celebrating the solstice since time immemorial. Gathering together at a time of great darkness to celebrate the return of the light.” She glanced back at Evie, set down her own mug, and sighed. “Sweetheart, I know you love your old aunt Martha, but I’m no dummy. You didn’t just come over here to visit and reject my gingersnaps. What do you need?”

Evie shifted uncomfortably. “I need . . .” She hesitated. “I need you to read my cards again.”

Aunt Martha sat back in her chair, surprised. “Your cards? But I thought you didn’t—”

“You were right, that first time,” Evie broke in. “About everything. The reading you did, the Celtic Cross, it brought me back home when I was down there in the dark. Remember?”

Aunt Martha’s nostrils flared. “Yes,” she said. “I remember.”

Evie hadn’t told her aunt everything that had happened, how the symbols from the tarot cards had given her the strength to fight back against the shadows, or how she’d heard Martha’s prayer in her head and followed her voice out of the maze of tunnels to safety. But she’d told her enough to make her understand that something uncanny had happened in the mines. That somehow, her missing cousin Holly Hobbie had brought her down there, and that Evie had made peace with her.

“You want to ask about Desmond,” Aunt Martha said, and shook her head. “Evie, I don’t think this is a good—”

“I need to do something!” Evie broke in, nearly upsetting her tea. It came out louder than she’d intended. Shaky. Desperate. She set the mug down on the table and sat back into the couch, folding her arms around herself. “Sorry,” she whispered. “I just . . . I was able to see things before, but now I can’t. It’s like I’m listening but I can’t hear anything. I need help. Please.”

Aunt Martha regarded her for a long moment. “All right,” she finally said. “As long as you understand that there are limitations to the answers the cards can provide. I’m thrilled that you see value in the tarot now, as I do, but they’re supposed to be used as a guide, not an instruction manual.”

“I understand,” Evie said. She’d say whatever Aunt Martha needed to hear to give her a reading. She didn’t know where else to turn.

“Come into the reading room, then.” Aunt Martha stood and led Evie next door. The heavy purple curtains blocked the sunlight, casting the room in deep shadow. Aunt Martha flitted about, lighting a lamp and a few candles, and turning on the calming, ethereal music she favored for her readings. Usually, the room smelled like sandalwood, but that day it had a distinctly different smell. It was earthy and sweet, and reminded her of winter.

“Frankincense and myrrh,” Aunt Martha said as if reading her thoughts. “A healing scent, don’t you think? Something to keep your spirit warm on those long, cold nights.” She plucked her usual Rider-Waite tarot deck from one of the shelves along the wall and settled into the overstuffed chair in the middle of the room, her silver chains tinkling softly as she moved. Evie squeezed past the low, tapestry-covered table and sat in the chair across from her. “I want you to take some slow, cleansing breaths, Evie,” Aunt Martha said, shuffling the cards. “Clear your mind. Focus on your breath going in and out.”

Evie did. It was hard to clear her mind, as cluttered as it was, but this was important. She listened to her breath and allowed herself to be pulled down into that deep, quiet place at the bottom of the swimming pool.

“Good.” Aunt Martha handed Evie the deck. “Now concentrate on your question as you shuffle the cards. When you’re satisfied, hand them back to me. We’ll just do a simple threecard draw this time. Past, present, and future.”

Evie nodded, closed her eyes, and mixed the cards. They were cool and smooth against her fingers. She thought of Desmond. His face, his eyes—the way the sunlight shone against his deep brown skin. She thought of the way he smiled when he asked her to homecoming with a hand-sewn message, and the way his lips felt against hers as they kissed for the first time in the pouring rain. Please tell me where he is, she thought. I have to know what’s happened to him. How do I find him? What do I have to do to get him back?

She opened her eyes and handed the cards back to her aunt. Martha took them reverently and, after a single, silent moment, laid the top three cards down on the table between them.

Aunt Martha pointed to them one by one.

“The past . . .”

The Three of Cups. Three women dancing in a circle, each raising a golden goblet in her hand.

“The present . . .”

The Hanged Man. A man dangling upside down by one ankle from a tree branch, his arms behind his back, a golden halo around his head.

“And the future.”

The last one made Evie gasp. It showed a man and woman chained to an altar, where a great horned monster perched, looming over them both.

The Devil.

Evie forced back the wave of fear that threatened to overcome her and concentrated on the cards. You can’t run away this time, she told herself. It’s too important. You have to face it, whatever it is.

The meaning of the first card, the Three of Cups, was so clear that it made a shiver roll down her spine. Three girls, Evie thought. Me, Holly, and Sarah.

“Playmate, come out and play with me, and bring your dollies three . . .”

The eerie song floated back to her, unbidden, and Evie suppressed a whimper rising from her throat. She knew that Holly and Sarah weren’t dangerous now, that Evie had helped bring Holly back to herself—but that didn’t erase the terror Evie had felt when she’d first encountered them.

The other two cards—her present and future—were more difficult to understand. That makes sense, Evie thought. If I understood what’s happening now, and what’s coming, I probably wouldn’t be here at all.

Aunt Martha was studying the cards, too, leaning close to the table, her long, slender fingers pressed thoughtfully to her lips. Finally, she sat back in her chair as if she’d reached a conclusion. “This . . . situation that you’re asking about. In the Three of Cups, the cards are saying that it came to be through a sisterhood of sorts. These three women are bound together—through friendship, family, or unseen connections. I realize that losing Desmond was a tragedy, but this card suggests that his loss wasn’t the only result of what happened. There was good there, too. You shouldn’t forget that.”

Evie thought of Holly, still trapped in a shadow of the past. Was she better off now that Evie had destroyed the darkness in her mind and given her back her humanity? She wasn’t so sure.

“In the present, we have the Hanged Man,” Aunt Martha went on. “This card suggests a trial, or a sacrifice.”

Evie sighed. “He looks pretty stuck. Just like I am right now.”

Aunt Martha cocked her head. “Perhaps that’s how you feel, but that’s not what this card is telling you. The Hanged Man isn’t in that position by accident, or as some kind of punishment. He’s there because he took a leap of faith. You see the ring of light around his head? That indicates enlightenment. His act of faith doesn’t just bring resolution, it also allows him to see the world from a new perspective, and to know when it’s the right moment to act. He’s there because he chose to jump, Evie. And he trusts that he’ll end up exactly where he’s meant to be.”

Evie nodded, feeling a lump rise in her throat. “And the last one?”

Aunt Martha tented her fingers and glanced down at the Devil card in Evie’s future. “Do you see how the man and woman are chained? This card often represents a sense of entrapment. You’re in a situation where it seems like there’s no way out. But like the Moon card—remember that one?—is is also a card of illusion. Because if you look closely, those chains around the woman’s neck are loose. She could take them off anytime, if she wanted to. The Devil wants you to lose hope, but if you push fear aside, you’ll see that the path home lies right before you.”

Thinking the reading was done, Evie sat back, frustrated. Not with Aunt Martha, but with herself, for thinking the tarot could actually give her a straight answer. Sure, the reading gave her a lot to think about, but nothing to go on, no way forward. She rubbed the heels of her hands into her eyes, trying to ward off the growing sense of panic in her belly.

“One more thing,” Aunt Martha said.

Evie looked up, hopeful.

“The Devil card,” Aunt Martha continued. “What I said is true, but it also has another meaning that might be significant.”

“What is it?” Evie asked.

“The Devil also represents our dark side—our shadow selves. The parts of us we don’t want to reveal to others, but that live inside us nonetheless. Those are chains that can never be broken. Our shadows follow us wherever we go. But they’ll only hurt us if we let them.”

Evie froze, and a cold chill crept up her spine.

Our shadows follow us wherever we go.

Aunt Martha was staring at her, concern plain on her face. “Are you all right?” she asked.

“Yeah,” Evie said. “It’s just . . . a lot to take in.”

“Which is why I didn’t think this was a good idea,” Aunt Martha said with a grimace. “You only just recognized your psychic skills, not to mention you’re going through a serious trauma. I don’t want to overwhelm you at a delicate time like this.”

Evie shook her head. She’d barely given a second thought to the fact that after years of believing she was hallucinating, of hiding all the things she saw and heard from other people, she finally had confirmation that, like her aunt, she had some psychic—or more specifically, spirit channeling—abilities.

“Yes, well, a lot of good my ‘powers’ are doing me now,” Evie muttered. “I finally figure out I have them, and they stop working.”

Aunt Martha reached out to touch Evie’s hand. “You need to be patient with yourself, sweetheart. All those traumatic experiences you just had? Those kinds of things can create a psychic block. It’s like . . . your spirit putting up a protective wall to shield itself from more damage.”

“Well, how do I get rid of it?” Evie asked.

“It’s different for everyone,” Aunt Martha said with a shrug. “For some people a special person or object can trigger the return of extrasensory perception. For others, it’s just time. Time to heal. Your mind put up that wall for a reason.”

Evie clenched her fists. “I don’t have time,” she retorted. “I have to find him!”

Aunt Martha licked her lips and sat back in her chair. “Evie,” she said slowly. “I know you don’t want to hear this, but you have to realize that Desmond probably isn’t coming—”

“He’s coming back,” Evie interrupted. “He’s out there, okay? I can feel him.” She put a hand over her heart, where the pain had been ever since the morning she’d found out he was gone. “I was right about Holly, and I’m right about this. You believe me, don’t you?”

Aunt Martha looked at her, Evie’s anguish mirrored in her eyes. “I believe that you feel him,” she said. “You felt Holly, too. Saw her. Touched her. But she’s not coming back, Evie. And Desmond might not be either.”

Evie stared back at her, silent, until a sob broke free of her throat. Then Aunt Martha was at her side, holding her as she cried.

“I’m so sorry for everything you’ve been through,” Aunt Martha whispered as she stroked her hair. “It’s too much. Too much for anyone. But it’s over now, okay? You’re safe.”

Evie pulled back. “It’s not over,” she said, her voice shaky. “That’s what I’m trying to tell you. That’s why I’m here. Whatever happened down there—it’s still happening.”

Aunt Martha gave her a searching look. “If that’s true,” she said, reaching back to pick up the Hanged Man from the table. “Then you need to remember to have faith.”

Evie took the card and ran her finger across the man’s serene face, surrounded by light. “But what if I don’t have the strength to jump?”

Aunt Martha smiled. “You will.”

When Evie reached the road to Hobbie House, she saw an unfamiliar green sedan parked in the grass nearby. The engine was off and the windows dark, so she couldn’t tell if anyone was inside. Pulling her coat tighter around her face, she sped up hoping to make it to the narrow lane as quickly as possible. Her boots crunched on the frozen ground as she went, her heart beating a little faster with each step.

But before she could reach the driveway, both car doors swung open and two men stepped out. “Miss Archer!” the driver called, motioning her to stop. He had slicked-back hair and a forgettable face. “My name is Tim Crane; I’m a reporter from the Pittsfield Post. If I could have just a moment of your time—”

“No,” Evie said, shaking her head. “Please, go away.” I thought I’d seen the last of these people, she thought, and she tried to walk past the reporter.

He stepped in front of her, blocking her way. “Now, Miss Archer, that’s no way to be. I thought you and your family would appreciate us waiting until all the hubbub died down before coming to speak to you. We just want to know what really happened down there in the mines—”

“I told the police everything they wanted to know,” Evie said. “There’s nothing more to say. Now, please—”

“Are you sure about that, Miss Archer?” the reporter said. “You’ve been made out to be quite the hero in this thing—rescuing your brother like you did—but what about your connection to the missing boy, Desmond King? I have witnesses on record saying that not only were you Mr. King’s homecoming date that night, but you were also exhibiting some strange behavior before leaving the school.”

The other man, taller and bearded, raised a camera to his eye and started snapping pictures. Evie raised a hand to block her face from the lens.

“Isn’t it true that you violently attacked another student at a local restaurant just days before the events in the mine?”

Click click click. Clickclickclickclick.

“Do you have a history of mental illness, Miss Archer?”

Evie tried to turn away and go back up the street, but the two reporters followed her every move. “Leave me alone!” she said.

The second man lowered his camera and glanced at his partner. “Tim, maybe we should go,” he said.

“No,” Crane said harshly. “We drove all this way for a story. We’re going to get one.” He turned back to Evie. “If you don’t tell us your side of this, then we’ll be forced to use what we’ve got. And believe me, you wouldn’t like the sound of it.”

Evie wanted to punch this man in his stupid, boring face, but she knew that doing so would only make things worse. All she needed was a photograph of her assaulting a reporter printed in the local newspaper.

“Well? Are you going to tell us the truth, Miss Archer?”

At that moment, another car turned onto the street. It wasn’t her mom’s little silver car, but a big black SUV bearing New York plates. It sped up, screeching to a stop in the middle of the road right in front of them.

Crane nearly jumped out of his skin at the car’s rapid approach, and the photographer fumbled with his equipment as he tried to get out of the way. Evie just stood there in shock as a barrel-chested, darkhaired man in a black Tshirt jumped out of the driver’s seat and stormed toward the reporters like a thunderhead.

“Hey, what’s your problem, buddy?” the reporter shouted. “You nearly killed us! I oughta—”

The dark-haired man took a fistful of the reporter’s shirt and shoved him to the ground. “Who the hell do you think you are, harassing her like that?” the man growled, dangerous. “You want me to call the police, or should I take care of this problem myself?” He advanced on the reporter, fists clenched at his sides.

Crane scrambled to his feet, rumpled and filthy, cowed by the man’s threats. “We don’t want any trouble, okay, buddy?” he said, his hands raised in surrender. “Just wanted to ask the young lady a couple questions. Didn’t mean her any harm. We’ll go, all right? We’re going. See?” He nudged the cameraman toward the green sedan, and they both hurried back to the car. Within a minute, they’d gunned the engine, spun the wheels in the gravel, and taken off back down the road.

Evie and the darkhaired man watched them go. Once they’d disappeared around the bend, the man wiped his workman’s hands on his gray utility pants and glanced up at her. He cleared his throat, awkwardness settling between them like a fog. “Hey there, chickadee,” he said.

Evie looked back at him, a swirl of emotions twisting through her heart. “Hi, Dad,” she said.

More in Series