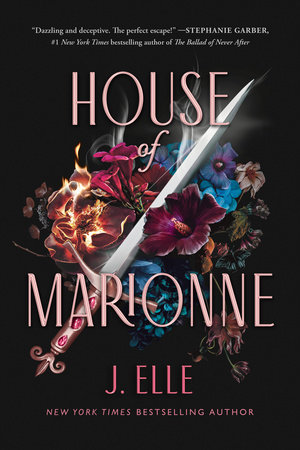

House of Marionne

Part of: House of Marionne

Ebook

$8.99

- Pages: 432 Pages

- Series: House of Marionne

- Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

- Imprint: Razorbill

- ISBN: 9780593527719

An Excerpt From

House of Marionne

I used to believe that magic was glittering, fanciful pretend.

Then I realized magic is real.

But it is dark and poisonous.

And the only way to hide from it

Is to not exist at all.

“Quell, are you listening?” Mom squeezes my hand as our car jerks to a stop outside the French Market on North Peters.

“Yes, get my pay for the week, in and out.”

“That’s my girl. Hurry now. I’ll circle.” She brushes my loose curls from my cheek with a cautious smile before I slip out of our ’99 Civic, a junkyard find, its blue paint dry and peeling. Before this car, it was an old yellow truck. And before that truck, it was the bus, everywhere. But Mom didn’t like not having a way to get up and go—run—at a moment’s notice. So she made sure to get really good at fixing up old finds.

Really good at hiding me.

Fourteen schools. Twelve years. Nine cities.

Every place is the same: a backdrop I blend into. Anytime Mom gets suspicious someone might know about the poison running through my veins, she stuffs our entire life into a tiny yellow, hard-shell suitcase. It’s perplexing that my entire existence can be tucked into something so small and shoved into the trunk of a car. At first, I’d stuff everything I could into my bag. Now, I just grab my tennis shoes, a phone charger, and my lucky key chain. The countless places we’ve moved and the blur of faces I’ll say goodbye to are the white space between memories, ellipses strung between unfinished sentences. I stopped asking where we’re going a long time ago.

Because running’s been a destination all on its own.

Humid air, thanks to the roaring Mississippi nearby, assaults me, sticking to my clammy skin. The back end of our rusted hatchback blares red before disappearing around a corner. With only two weeks of high school left, I’m trying to work as much as I can to save up enough for the big plans Mom and I have.

To finally move somewhere and stay.

If a caged bird sings of freedom, and a song can be a wordless utterance, a wish, a burning desire, then I sing of salty air and sand between my toes. Of a home that’s not a moving target. After graduation, our plan is to find some small beach town—a real beach, not like the muddy water we’ve been around these last six months in New Orleans—and blend in with the sand.

Only a couple more weeks.

I graft myself into the afternoon commotion of the congested Market, and it’s like slipping into a worn pair of shoes. I disappear into the throng of shoppers in the outdoor pavilion with my chin to my chest, hands tucked in my pockets.

Be forgettable.

Mrs. Broussard should have my money for my shifts last week. She is a local confectioner whose family has been in the business of pralines since there was such a thing. The Market buzzes with an energy that slows my steps. Too many people. The usual spot where Mrs. Broussard sets up her table of goods is taken up by a person peddling various levels of heat—hot sauces. My pulse ticks faster at the hiccup.

I weave in and out of the crowd, avoiding curious eyes and looking for a bandana covering a head of pinned gray hair. My fingers prickle with a cold ache, a familiar sign that this curse in my veins—my toushana—is stirring. I swallow, urging it back down, pleading with it to calm. It’s safer to be invisible; it’s safer to be no one.

“Quell?”

I flinch at the sound of my name.

“That you, girl?” Mrs. Broussard waves me toward her, and the line snaked at her table parts. My skin burns, feeling her customers’ stares.No eye contact.

“Tonta’lise got here before me, yeah. Had to set up my whole show ova here. She know damn well I use dat spot eva day. But here she come, tryin’ to get my customers.” Her hand rests on her hip. “You come for ya money?”

I nod and Mrs. Broussard pulls an envelope out of her apron. This is the first job Mom ever let me have, because we need the money and Mrs. Broussard doesn’t ask a lot of questions. She pays me in cash and has only ever asked my name once.

“You gone do extra hours for me next week?”

“Not until school’s out.”

“Very good. Don’t linger ’round these parts, che. Gone get outta here before it get dark, ya hear?”

The thick envelope in my hand soothes my nerves. I count it. Twice. My lips curl as I thank Mrs. Broussard and turn to go. The crowd has thickened like a nice roux.Be unpredictable. A cluster of tourists lodge in the entryway and I scan for another exit. Away from the vendors, near an abandoned pop-up tent full of fleur-de-lis candleholders, is a sign for the bathrooms. A red exit sign blares next to it and I head that way. Mom will worry if I take too long.

The winding hallway toward the bathrooms twists and the light bulbs overhead flicker. Small exit arrows glow red, urging me farther down the hall. I expect to spot the bathrooms but don’t see them yet. The Market pavilion is open to the outdoors, so there should be sunlight up ahead. The fluorescents flicker again and I walk slower. This doesn’t feel right. Worry bites at me and I turn to go back the way I came.

But there’s a wall there.

A shape of something, like a shadow or trick of light, forms a fleur-like shape on its stuccoed surface. I blink and it’s gone. My heart stumbles; my toushana unfurls in my bones, dancing with my panic, threatening as it does in warning that it might rise up in me soon.

I turn, but in every direction the walls have shifted or closed in. There are no bathroom signs, no blaring red light pointing toward an exit anymore.

“Memento sumptus,” someone says. The voice is coming from a narrow door that blends seamlessly with the wall. Caution tugs at me like a tether. Pressed carefully to the door, I listen, hands hooked behind myself just in case. Strained voices tangle around each other in a whispered argument. There are a pair of men, it sounds like. I listen again and hear several more. I teeter forward on my toes ever so slightly, pressing my weight against the door to ease it open a sliver.

Inside, dark-robed men encircle another bound to a chair. Around them are rows of stacked barrels marked with a thorny branch coiled around a black sun and words in a language I don’t understand.

“Go on, Sand,” one says after refilling a barrel with a pale liquid. “We’ll clean up.”

A blond fellow lassos his arm in the air and the dozen barrels tremor. A haze fills the air, rippling like rain on a window. It clears and he does it again, and this time the barrels disappear. I squint, my heart lodged in my throat.

I glare at my hands in confusion, and I can still picture the wisps of darkness that bleed through my fingertips when my toushana shows itself, destroying anything I touch. When I was little, I’d called it “the black.” Then as I grew to know its nasty nature, “the curse.” Mom finally corrected me a few years back after someone overheard me complaining about it. Toushana is its name. Some genetic malfunction, Mom had said. She’s lying. But Mom does that. I’ve heard her mutter to herself about this poison I have.

She called it magic.

But whatever these men are doing appears quite different. My nails dig into the door’s frame as I peer harder into the dimly lit room. I’ve never seen magic that isn’t my own.

“What was the order, Charlie?” asks Sand. The others in the room watch from the shadows.

“No prisoners. Not today.” Charlie plants his hands on his knees and glares at their captive, now at eye level. “May Sola Sfenti judge you fairly.”

“Screw you and your Sun God,” the bound man spits as Charlie pulls deep from a fat cigar. He blows smoke into the captive’s face. Then he does something with his fingers, too fast and too far away for me to make out. The bound man throws his head back, choking and contorting in pain, his wrists and ankles rubbed red from their hold on him. The smoke from Charlie’s lips hovers like a cloud around his face, consuming and suffocating. The man gasps for breath and in moments, his writhing stops. His head lolls and I stumble backward, lacing my fingers, trying to slow my hammering pulse.He’s . . . dead. That man, they . . .

“Fratis fortuna.” The voice comes from behind me. I turn and there is a man in a dark suit, same as the ones the men I just saw were wearing. But unlike the others, a gleaming dark mask slopes across this man’s brows, over his nose, its ornate carvings tapering off into his high cheekbones. His expression hardens at my silence.

I step backward, my back hard against the wall. There’s nowhere for me to hide. His brows knit with intrigue and my heart patters faster. My toushana’s ache deepens, my hands growing colder. I have minutes, maybe, until it will rip through my fingertips angrily like a spewing burst pipe. Pressure swells in my chest. Run. I step aside. His hand latches onto my wrist, but I feel it around my throat.

“What are you doing back here?”

My envelope from my job slips from my fingers, and I try to dash for it as it tumbles to the pavement.

“Ah, ah. Hold still.” His long coat is tightly buttoned all the way up to his neck, and a round piece of silver gleams at me from his throat. An image is engraved on it, a Roman-style column, with a jagged crack running across its front as if it’s been broken in half. I squint, trying to remember if I’ve ever seen that symbol before. Thick brows shade his narrowed expression. “Answer the question.”

“I got lost trying to find the exit. I thought it was near the bathrooms.” I tug against his grip, but he doesn’t let go. He glances just past me at what was a door, but is solid stone wall now. My heart hiccups. “I—I didn’t go in there, if that’s what you’re thinking.”

“In . . . where?”

“There was a door, but I could tell it wasn’t the bathroom, so I turned around to leave. Iswear!” A lie is too risky. People believe half-truths much more easily.

“What’s your name?”

“I—”

The answer sticks in my throat, magic fluttering around in me like a moth searching for a place to land. Mom changes my name each time we move, cycling through the same three or four. QuellJewel. Not Quell Marionne. Who lives at 711 Liberty Street. Born in a small town outside the city. New to the area. Whose dad’s job requires him to travel a lot. Two parents means fewer questions. My script, the drill Mom has run through my head year after year, hangs on my lips. All lies seasoned with enough truth, the proper inflection, the warmth of a genuine smile, to make them feel true. To make the veneer of a life we’ve lived, I’ve lived, for as long as I can remember, real.

“I’m Quell.”

More in Series