The 39 Deaths of Adam Strand

In this hyper-edgy coming-of-age story told in stark, arresting prose, Alex Award-winning author Gregory Galloway finds hope and understanding in the blackest humor.

“A riveting second novel that explores the issue of suicide with a philosophical, never sensational, approach. . . . Requires careful reading of the issues it addresses, but the effort is well worth it.”

—Booklist, starred review

“Fans of gritty realistic fiction such as Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak and Jay Asher’s Thirteen Reasons Why will appreciate Adam’s thoughtful, authentic adolescent voice, and the honesty and boldness with which Galloway treats the issue of suicide.”

—SLJ

“A compelling, sophisticated novel that explores the relationship between death and the meaning of life.”

—BCCB

“Galloway has written a thoughtful, darkly humorous, philosophical novel with great chapter titles that reads, in a way, like homage to some of the greatest writers of literature.”

—VOYA

“A moody, compelling read.”—Kirkus Reviews

- Pages: 336 Pages

- Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

- Imprint: Speak

- ISBN: 9781101592984

An Excerpt From

The 39 Deaths of Adam Strand

The angel of death?

Some people think the angel looks peaceful, raising her arms in a gesture of acceptance and grace, while others think she looks sad, disappointed in her inability to rise off her pedestal. I think she’s a little pissed, waiting there to catch someone jumping off the bridge, her arms still empty after all this time. I would like to jump to her, but not to have her catch me. I’d like to land on her and knock her off her perch. It seems like a good goal, to hit her, to land on her, to be held by her—a morbid game, a strange version of ring toss. It never happened. The closest I ever came was hitting the pedestal. It would have counted only in horseshoes.

I have killed myself thirty-nine times. Usually when I say this—and I rarely do—people misunderstand me. They think I mean I have tried thirty-nine times, that I have tried and failed. Do not misunderstand me—I have succeeded thirty-nine times; it is not me who has failed. It is something else.

Other Books You May Enjoy

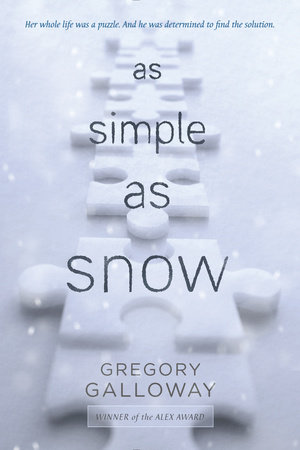

As Simple As Snow Gregory Galloway

The Fault in Our Stars John Green

If I Stay Gayle Forman

Jerk, California Jonathan Friesen

Looking for Alaska John Green

The Rules of Survival Nancy Werlin

Tales of the Madman Underground John Barnes

Thirteen Reasons Why Jay Asher

Twisted Laurie Halse Anderson

The Vast Fields of Ordinary Nick Burd

Where She Went Gayle Forman

Willow Julia Hoban

The 39 Deaths of

Adam Strand

GREGORY GALLOWAY

Dutton Books

An imprint of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

“The best thing that eternal law ever ordained was that it allowed to us one entrance into life, but many exits.”

—SENECA, LETTER TO LUCILIUS (70)

“Lo! I leave corpses wherever I go.”

—HERMAN MELVILLE, PIERRE

“Men always come back. They’re so absurd.”

—JEAN COCTEAU, ORPHÉE

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

Prologue

(“and shall come forth, they that have done good”)

Against the dark sky there is a darker shadow. It is motionless for a moment, quiet and still, barely perceptible on the edge of a dark cliff, standing against the dark sky, a black patch on a black background, and then it’s gone. It is falling—the camera catches it as it falls and tries to stay with it, losing it a few times, falling behind so there is only the black bluff before the figure reappears again. It is unclear what it is or where it is, but you can tell that it’s falling through the air, dropping from some height. You know it can’t be good, and maybe, even before the next part, you begin to realize that the falling object is a person—you don’t know who it is, but you know it’s someone falling and that they have jumped from something solid into nothingness.

There’s nothing more than that—the image of a person falling. You don’t see the impact, you don’t even see the body as it ends its descent even though the camera is right on it—it’s too dark, too far away, too many other dark shapes around it—bushes, boulders, the dark hillside and the night swallowing up everything—but the next shot is an image of the body, the camera poised directly over him, over his broken and lifeless body. There’s more light, a harsh light thrown on the figure from behind the camera—you can see blood and broken bones as the camera moves quickly across the body before stopping on the face. You can see him clearly on the ground; his face is calm, without a scratch on it, as if he had laid down on the ground, and the camera stays there on the closed eyes and quiet mouth, in stark contrast to the mangled body below. The camera moves position; the light lurches a few times, but the face remains the same. The image jumps and then jumps again; the camera twitches with impatience more than a few times. There’s no sound, only the image of the boy on the ground, until suddenly he opens his eyes.

I can’t watch it; I can describe it, but I can’t watch it. Probably because I’m in it. That’s me opening my eyes. I’m the one who jumped. I’ve done it lots of times.

ONE

The summer came for me with unusual and unwanted force, as if I suddenly found myself stuck in a vise and then feel its grip slowly tighten day after day, week after week, an annoying discomfort that becomes painful, almost unbearable. But then, as you will find out, there are a lot of things I find unbearable. Sometimes I’m the only one who feels that way, I think. For instance, I might have been the only person who didn’t want school to end. At least it was something to do, some distraction for a few hours during the day. The summer brought nothing but dread and determination. There was nothing I wanted from it, endless days of stale heat and humidity, long nights of dull talk and duller senses. It would be the summer of my seventeenth birthday, the distant looming of our last year in high school, and the knowledge that I was never meant to see any of it, had never wanted it, and would try anything to put a stop to it. It was the summer of illness and death and near-death, the time when I would finally, I thought, for once and for all, for forever, kill myself one last time. It should have been a great summer.

We lived on the edges of town during the long months of summer, spending our days on a small triangle of land we called The Point that stuck out into the river just north of town. It was our own isolated spot, practically an island, cut off from the rest of the world by the river on one side and the railroad tracks on the other. No one bothered us, which was fine by me, and we biked there almost every summer day and did nothing but fish and drink. Then we biked home and waited until after dinner to meet up again at the southern end of town, near the bridge that connected Iowa and Illinois, and drank some more. There really wasn’t much else to do.

While there’s nothing at The Point except tall grass and a pile of empty cans and bottles, there is a park underneath the bridge at the southern edge of town. There’s The Thorpe, an old steamboat grounded on the banks of the river near the park, with its white wooden sides stripping off and the large paddle wheel splintering and decaying from age and the floodwaters that attack it every spring. It wasn’t always useless, of course. It once had purpose, even when they took it out of the water and nailed it to the ground. The Thorpe used to be a museum, a place where people paid to go on board and look around at the small, cramped decks, where they could look out at the river and maybe imagine what a lousy life it must have been to be on board such a claptrap of a boat every day, going up and down the river over and over and where tourists could thank someone that their life was better than that. But once the casinos opened with their flashy, unrealistic replicas of the same steamboats, people seemed to lose interest in the real thing. It’s nothing now, closed to the public, can’t float, would cost too much to haul away for trash, so it sits and rots like the bleached carcass of some extinct animal. We don’t even bother to go there much anymore to climb around inside; everything has been stripped or stolen or smashed. Besides, we like to hang out over by the angel.

She stands across the parking lot from the steamboat, closer to the bridge, with her head tilted up toward the traffic, her arms outstretched as if she’s starting to reach toward the sky or the bridge itself, her wings starting to spread behind her. Maybe she’s getting ready to fly off, but she hasn’t moved an inch since 1921, when she was erected in memory of the World War I veterans. We think. You can read the date, but most of the other words below have been chipped away from the stone by vandals who have been coming here a lot longer than we have. I don’t know why everyone has the same thought, to hack away at the base. Maybe they think one piece here or there won’t make a difference, but then before you know it, the whole thing is chopped off. There are no new ideas, I guess.

The marble angel was probably white once, like a statuary you’d see in front of a church or in the cemetery, but she has turned a grimy gray, almost black from the pollution constantly spewing from the factories in town: General Mills, which makes corn syrup, and Universal Wheel, which makes wheels for trains, and Union Carbide, which makes . . . I don’t know what they make, pollution mostly, it seems. We’re not sure what the angel is doing down by the river, standing there with her face tilted slightly away from the water, her eyes hooded and darkened by years of soot and dirt. It’s hard to tell where she’s looking—toward the bridge, watching it or watching the traffic as it moves back and forth, or is she looking at the sky, toward heaven, or is she looking lower, watching the river move past her, or maybe she’s looking across the river at Illinois, waiting for something or someone to arrive on the other bank. Maybe she isn’t looking at anything; it’s hard to tell. Her eyes seem dead and lifeless in certain light. Maybe she’s blind, her arms reaching out to feel her way through the world, blind like Justice or a wounded Greek god. She didn’t seem to be in anguish or distress; she seemed sad, wanting something, I thought, but maybe I was wrong. I thought about her too much.

Some people think the angel looks peaceful, raising her arms in a gesture of acceptance and grace, while others think she looks sad, disappointed in her inability to rise off her pedestal. I think she’s a little pissed, waiting there to catch someone jumping off the bridge, her arms still empty after all this time. I would like to jump to her, but not to have her catch me. I’d like to land on her and knock her off her perch. It seemed like a good goal, to hit her, to land on her, to be held by her—a morbid game, a strange version of ring toss. It never happened. The closest I ever came was hitting the pedestal. It would have counted only in horseshoes.

I have killed myself thirty-nine times. Usually when I say this—and I rarely do—people misunderstand me. They think I mean that I have tried thirty-nine times, that I have tried and failed. Do not misunderstand me—I have succeeded thirty-nine times; it is not me who has failed. It is something else.

I have killed myself thirty-nine times—which most people think is a lot. It’s really a small number when you think about it. I mean, there are a lot more days I haven’t killed myself. There are a lot more times I’ve decided not to try to end it all than days when I have. I’ve said that before—no one thinks it’s funny except me. They’re still fixated on thirty-nine, thinking that it’s a lot. Maybe it is—all I know is that it’s thirty-eight times more than I wanted and one less than I need. I’m still here; that’s the worst part of the whole thing, unable to accomplish what should have been one small, inconsequential task but has become a larger failing to shape my own destiny. It is not the story I wanted to tell. The truth of it is, I didn’t want any story at all. That was the whole point. Instead, I have had to account for each death and much more. I have become a scholar of death, a student of its various ways, and the more I learn, the less I know.

Thirty-nine. It seems small when I write it and smaller still when I break it down into how it was done. This is how I’ve done it: eighteen times by jumping (from bridge or building or other high place and once from the back of a truck), five by drowning, five by asphyxiation, four by poison/overdose, three by hanging, one by fire, one by gun, one by chain saw, and one by train. There are reasons for this. I live within a few miles of two bridges and a high bluff that look down to the Mississippi River. I can’t go near the bluff or cross either bridge without seeing myself leaping out into the air, free-falling down toward a certain end. It’s like a video that starts playing in my head every time I see the bridges or the bluff. I’ve watched that video thousands of times. It’s my favorite, I guess. I’m a leaper.

I know this isn’t normal. I’m not normal. I’m not even normal in how I choose to kill myself. Gunshot is usually the way to go—over sixty percent of the people who kill themselves use a gun. More than 18,000 people a year. I don’t get it. For one, it’s messy, and someone’s going to have to clean up the mess you leave behind. Then there’s the problem of getting a gun (if you’re underage like me, it’s a problem—not a big one, but still), then you have to load it (if necessary) and place it to your head, in your mouth, under your chin, and then you have to pull the trigger. There’s too many steps, too much thinking involved, too much time to think, and too many times to wait, pause, stop. It’s not like jumping—after the first step it’s all over, nothing else to do but enjoy the ride down. Maybe I’m a coward, but I couldn’t use a gun, not again anyway. Forget the maybe part. I am a coward. I know that. It’s part of my problem.

I’ve been looked at by doctors and more doctors, doctors of every kind. They’ve poked and prodded at me, analyzed me, examined me, and talked to me—talked and talked and talked—and I have left them, almost without exception, shaking their heads. I don’t want anything from them anyway, only to be left alone, but people (my family, mostly) want some explanation, some simple answer. Of course there are no easy answers. I’m a freak. There’s something inside me that compels me to do what I do and something that prevents it as well. How screwed up is that? I don’t get it. No one does, but mostly they think the problem is in my head. Maybe it is, but for me there seemed to be no other way to go about it. I look at the people around me—my parents especially—and I can’t figure out how they can live the way they do, how they can go on day after day. My father is not an unhappy man, but he isn’t anywhere close to happy either. He seems to go through the motions, an efficient program of actions—wake, shower, eat, work, eat, watch TV, sleep, repeat—micromanaging his existence to the minute, eliminating any wasted effort or spontaneity. He’s the type of guy who thinks there’s a right way and a wrong way for toilet paper to come off the roll—he’s contemplated the issue, put serious thought to it, maybe even performed a test or two until it’s a problem solved and he doesn’t have to think about it anymore, unless it’s done wrong and then he has to correct it and educate the person who has created the problem (usually me). It’s over, by the way, never under.

I understand his desire for control—we are alike in that way. Except I take enjoyment in my actions—some of them—as hard as that might seem. I’m frustrated, restless, bored (very), but I’m not unhappy, depressed, or whatever other label they’ve tried to pin on me, and I’m certainly not an automaton like my father. I have more control of my life than they give me credit for (and less than I would like, believe me). I see that my father seems to take no comfort in his control, but he has no complaints either. His is a smooth, uninteresting road, which he has carefully, meticulously paved for himself.

While my father has few complaints—and the complaints he does have seem to be the same few repeated over and over—my mother does little but complain. Each day for her is a series of small traps that were set in the night while she was asleep, nothing lethal, only annoying, like getting caught time after time in those paper Chinese handcuffs. The trouble is, everything is a trap for my mother—the weather, the sky, the sun, the clock. She complains about the length of the straps on her purse: one day they are too long, the next too short; she complains about the humidity and its effects on her clothes and hair; she complains about the time it takes to make her morning tea and then complains that it’s always too hot, which only traps her deeper inside the clock. While my father seems able to control every tick, my mother seems to always wake up ten minutes too late. She’s always in a rush, always behind, no matter what she does—time is conspiring against her. She complains about it every day, and of course it’s never anything she’s done. Her road is anything but smooth, but she puts no effort into repair. Her job, it seems, is to find fault, not to fix anything. She moves through each day beset with problems, and she is continually providing her own narration in a half-hushed muttering of disappointment and correction. You can never make out exactly what she says, only a word or two here and there, but her cadence is always the same, like some epic blues song she is fated to sing over and over.

There are two things my mother never complained about: my brother and my father. She rarely complained about me, or not nearly as much as I gave her reason. Complaining is her way to feel as if she has accomplished something—the world is against her, but she is not defeated. She knows what’s wrong with the world and everyone in it. They might set their traps, but she won’t stay caught. She has her reasons—a need to vent her energetic anger or whatever that might help her get through her day—just as I have mine, or don’t. I try not to peer too deeply into my whys; it’s a tangle I’d prefer not to spend time picking apart, just as the whys of my return time after time seem inexplicable, beyond current understanding and reasonable explanation. No one seems as interested in the why of my refusal to leave this life, not nearly as interested in the why of my desire to leave. That they think they can fix. Why is that? Everybody’s got their own disease, I think, but not everyone’s got their own cure. I thought I did, but I was wrong.

My father is a loan officer down at the bank. Unfortunately, he’s not one of those guys who ruined the economy. He didn’t give anyone a loan he shouldn’t have, didn’t fudge any numbers, take any risks he shouldn’t have, didn’t do anything one inch this side of illegal or unethical. He’s a safe-bet man, limited liability, which is why he works in a small bank in a small town, why we don’t live in a bigger house and drive a better car. The most interesting thing I can tell you about him is that he is an amateur efficiency expert. He puts a stopwatch to everything—how long we take to wake up, how long we spend in the shower, how long we take to get dressed, how long to eat breakfast, how long to leave in the morning, how long I spend on the computer. This is where I get my interest in details, I suppose, my fascination with data, all that crap, a trait I only developed because of a certain gene passed down from my father. You can’t outrun your blood. I don’t try to impose my interests on others, usually. That’s all my father does. He has timed it all and somehow developed an “optimal” time for all of these things. Overages are quickly reported. If you are in the bathroom longer than ten minutes in the morning, he’s there banging on the door, yelling that you’re wasting water or wasting his time.

My mother and I are the prime culprits in the household, make no mistake about that—we travel from room to room wasting something, demonstrating the great waste that seems so infuriatingly obvious to my father but still remains somewhere outside our mind’s grasp. He would be better off living alone, with his rooms dark and quiet, his electricity tucked safely inside the walls, the water waiting inside the pipes, the dials on all the meters creeping forward as slowly as possible, not flying as you would think they are in our house. He tries to educate us, but we are slow learners. At least my father is not a stern man; in fact, he thinks he has a sense of humor.

My father likes to quote the best thinkers of his day—Bill Murray, David Letterman, Peter Sellers, everyone from M*A*S*H, and especially Woody Allen. “The world is separated into two categories,” he said, trying to recite something from Annie Hall, “the tragic and the miserable. The tragic are people with handicaps, cripples, mentally impaired, all of that. And the rest of us are miserable. You’re definitely not tragic, so you should be happy that you’re miserable.” The problem was, I wasn’t miserable. I knew I wasn’t tragic (my father was wrong about the categories, btw; horrible is the other category, according to Woody), but I never considered my life too miserable. We were a solid middle-class family in a small working-class town. My parents loved each other and me and my brother, as far as that went, and we never struggled or faced any hardship that was out of the ordinary. I was lucky; I knew that. It was something else.

“What’s wrong with you?” my father asked me after I awoke from number eight.

“I’m bored. I’m the chairman of the bored.” I didn’t know what to say; I thought he’d like it, think it was funny. It seemed like something one of his guys would say.

“Boredom is just another form of depression,” he said. I don’t know what movie he got that from.

“If you’re bored, do something,” my mother said. “Read a book, watch TV, take a walk. Call somebody. This is no way to behave just because you’re bored.”

I did do something. Over and over. It’s not what they had in mind.

If you could pick four people to be stranded on a desert island with, who would they be? I know I wouldn’t pick my friends, but then, I spent almost every day of the summer with them at The Point, which is practically the same thing. There’s no one else around, our phones don’t work, Todd has baseball practice or games, and Jodi won’t come there. So it’s just me and Ash and Bruce and Darryl and Vern. They remind me that the vise is turning.

I remember my mother once saying something along the lines of “you only find out who your true friends are when you’re dead,” which stuck with me. I’ve been dead thirty-nine times and I’m still not sure who my real friends are, and I’m less sure now than ever. I’ve been with the same hodgepodge collection of different personalities for most of my life. I’ve known most of them for at least eight years or more. We don’t seem to like the same things as a whole, or no longer agree on most things, but it is the few things we agree on that seem to keep us connected. That and the fact that we have been hanging out together for so long, it has become a repetition that has excluded most others, keeping us insulated and isolated, together and apart.

The Point is over a mile from my house, down River Road—we always said “down,” even though it was actually north, but the road sloped down from the height of the bluff to level with the river. The railroad tracks were built up on a mound, blocking the view of the river in some spots. We rode our bikes there in the morning and dragged them up and over the raised tracks and then down again and through bushes and tall grass and weeds. There had been a path cut years ago, and every spring we tried to find it again and clear a narrow trail to the end of the triangle.

We spent most of our time fishing, if that’s what you could call it; it wasn’t really fishing, but mostly just having a line in the water. We didn’t really care if we caught anything. Having a fish on the end of a hook was actually more of a nuisance—we preferred to go to the same spot every day and drink and do as little as possible until it was time to go home in the evening.

“You know the only difference between fishing and not fishing?” Ash said. “In one of them you wish you weren’t fishing.”

We all arrived earlier than usual one morning and waited for Darryl to arrive with another bottle of wine. He’d found (or stolen) a case of it the last week of school, and had hidden the bottles in some undisclosed spot, and arrived every day with another bottle we let cool in the water for a few hours before we cracked it open. It was, we knew, some cheap, supermarket wine, but we treated it as if it were liquid gold, as if the act of drinking it somehow improved us, made us superior to our former selves, elevated us to a better, more refined class. Ash even arrived the second day with legitimate wineglasses. They weren’t anything fancy, old stemware he’d bought at a yard sale, but we treated them with care and carefully measured the wine from each bottle into equal parts, holding the rare drink in our new glasses and swirling it around a few times as we marveled at our good fortune and then guzzled it down with greedy delight. We felt better about ourselves because of the wine, there’s no doubt about that, and those days would have been unbearable without it. There were some days when I could have handled an entire case of it and not feel the least bit drunk and other days when a few swallows would have made me unsteady. “It’s the sun,” Todd said. I don’t think so; it was me. The trick was to act the same drunk as you acted sober. You had to maintain composure no matter what. We got drunk to feel different inside, not to behave like morons.

I was the last one to arrive one morning, and all of them, even Todd on one of his rare appearances at The Point, were already there, crowded at the northern edge, intently studying the water. They waved for me to join them and I hurried to the spot to discover a large dead cow that had washed up against our shore and had become entangled in some tree branches that had collected there over the spring. It was a large red-and-white Hereford, lying sideways among the tangle of branches, with a white head and white underbelly. “Beef,” Ash said. “It’s what’s for dinner.” Nobody laughed. We didn’t know of any farms along the river. “Maybe somebody dumped her,” Darryl said. We all continued to stand on the bank and look at the large body suspended in the water. I wondered if it had fallen in—maybe it had gotten loose and lost and disoriented and had fallen into the river in the night—or if it had been dumped into the water, but it was too big for one person to haul around. I wondered if she’d jumped. Maybe she just thought to hell with it, she wasn’t going to wait around to get shipped off to the slaughterhouse and take a shot to the head and have every part of her chopped up and ground up and shipped who knows where.

The rest of them spent very little time wondering how it got there, where it came from, and how far it traveled; we all marveled at our luck that this large beast had found us, had made its way from some spot upriver to lodge directly in front of us. We thought we were lucky.

The cow was slightly bloated and its hide looked slimy in the water. Its legs were hidden by the dried tangle of limbs, but it did not look in distress. In fact, the animal looked gentle and calm; its mouth was open and the water pushed its way up through the opening and spilled out over the jaw in a frequent drool, as if it had laid down in order to take a much needed nap and fell quickly into a deep sleep. Vern wanted to get a branch and free the dead animal and watch it float down the river. Darryl wanted to scoop out the eye and cut it in half to see what it was like inside. Todd and Ash wanted to leave it alone so we could watch it decay and turn into a skeleton.

It was huge, over a thousand pounds of literally deadweight—the largest corpse any of us would probably ever see—washed up right in front of us for all of us to look at, examine, observe, poke, and prod on limited occasions. We, of course, had to vote on it. You couldn’t touch it without everyone being present, and you could only touch it, poke at it, with a long stick if everyone agreed. The main objective, we decided, was to watch it rot, and we were afraid that poking at it too much would somehow disrupt the natural course of things. It was like trying to not pick at a scab—sometimes you don’t care about the consequences and you have to pick even if it all turns bloody.

Bruce had already named it. “Strand,” he said. “Get it?” I did. We left it there, my namesake, drooling at us day after day, swelling even more in the heat until it began to ooze froth and filth into the water. Vern brought his camera every day and shot a few minutes of video; he tried to stand in the same spot and hold the camera at the same angle so he could make what he called “a poor man’s time lapse,” but he never got it right. The edited piece was a mess, with the cow jumping all over the place, magically moving from one part of the frame to the other, and of course he had to junk it up by putting shots of the rest of us in the thing—I didn’t want him taking my picture at all, but he caught me napping one afternoon and used it in the video with the cow. It was a mess, but it still looked cool and racked up more than five thousand views in the first few days after Vern posted it. It wasn’t even the finished video; we were still waiting for the last of the flesh to disappear and reveal the complete skeleton. “I told you I’d make Strand famous,” he joked.

Vern took it for granted that he was going to be famous. The details were vague, but the end was always the same—somehow, someday, someone would come through town and discover the obvious genius that is Vern and would want to make him a star. He talked about it as if it were already happening, as if that person were on his way right now. It didn’t matter that Vern had no discernible talent or that no one like that ever came through town.

“You don’t have to have talent,” Vern said. “Some of the most famous singers can’t sing, some of the most famous actors can’t act, and some of the most famous people in the world can’t do anything at all except be famous. Any moron can be famous.”

“You might be overqualified, then,” Bruce said.

“That’s a beer,” Vern said.

“No it isn’t,” Bruce said.

“You broke the ban.” There had been lots of bans over the past year or so. In fact, it seems as if we’ve banned everything—jokes about looks (“You can’t make fun of something you can’t control” is how Ash had introduced it), jokes about mothers, “gay” jokes, “racist” jokes, “sexist” jokes; we even banned swearing for a short while because Todd had heard somewhere that cursing was nothing more than a substitute for action, and that idea rubbed him the wrong way. He wanted action—this is from a guy who sits around most nights doing little more than tipping a bottle to his mouth. That’s action.

It took a majority to implement a ban, but only a unanimous vote could lift it. It was becoming very complicated—too many rules and regulations, votes and vetoes. There had even been a discussion about banning bans, but that went nowhere. Sometimes I wondered if we were friends or some horrible society like the Shriners or the city council. We had decided, voted on it, that we couldn’t call each other a moron or an idiot or say that someone was stupid. There had even been, a while ago, a debate as to whether you could use the phrase “that’s stupid.” It had been thrown around a lot (mostly by me, I have to say) and Vern in particular had been on the receiving end of much of its usage, usually referring to all the stupid things he said. Which were stupid. Which was almost everything. But without Todd around as much that summer, Vern had the votes, and a lot of stupid bans had been passed. The moron ban was one of them.

“Didn’t we lift that ban?”

“No,” Vern said. “Bruce owes me a beer.”

“Ban or no ban, I don’t owe you,” Bruce said. “I didn’t call you anything.”

“We need a vote,” Vern said.

“No vote,” Bruce said.

“Just pay him the beer.”

Bruce handed over the beer. “It pays to be a moron, doesn’t it?” Vern didn’t ask him for the second beer.

When Vern wasn’t talking about himself becoming famous on his own, he was talking about becoming famous by making me famous. His big idea was for me to have my own reality show.

“How would that work?”

“Every week viewers could vote on how they wanted you to die and then you have to do whatever the winning thing is,” Vern said.

“That would last two weeks, tops,” Bruce said.

“Okay,” Vern said. “What if you were a serial killer, but you only have one victim—yourself. I bet we could sell it with that one-sentence pitch.”

“That’s worse than the other one. How would that play out?”

“I don’t know what the show would be, all right,” Vern said, “but the concept is still good. They’d figure out the details. I mean, just look at all the people who have shows who have absolutely no talent whatsoever. You can at least do something, something no one else can do. They would give you a show. We should make a video and send it in. I bet you’d get an offer immediately. You’d be famous.”

“I don’t want to be on TV.” I didn’t know how to explain to Vern that there was something inherently contradictory about what I wanted and then trying to be famous for it. I wanted to reduce the number of people who knew me to zero, not multiply it. If I could, I would erase all memory of me.

“How about Let’s Kill Adam Strand for the name of the show?” Vern said.

“Seems too gleeful.”

“But it should be fun, right? Or else no one will watch,” Vern said.

“How about Die, Adam, Die?” Bruce said.

“Faster, Faster, Adam Strand, Die, Die.” Vern wouldn’t let it drop. “Or you could take over that 1,000 Ways to Die, so it’s just you every time. We should go out to LA.”

“I thought your guy was coming here,” Bruce said.

“What guy?”

“The guy that’s going to make you famous,” Bruce said.

“I meant for Adam,” Vern said.

“I’m not going anywhere.”

“Don’t worry, none of us are.”

None of us will amount to anything—that’s the prevailing wisdom of our parents, teachers, coaches, friends, just about anyone you could ask—no one from here has ever amounted to much, no one famous or noteworthy—everyone has been nothing more than the least they could be, small and subordinate, but no less necessary, I guess. It doesn’t bother me, but it bugs the shit out of Vern, and Ash and the rest, even Todd. They all want to leave, get as far from here as possible, do something better, live bigger—they all want it, talk about it, but I think Todd’s the only one who would actually work for it. The rest of them are only talk.

It doesn’t matter where we are—at The Point or down by the bridge, in the park, on the golf course, and in Todd’s brother’s car, if he can get it—we always do the same thing. Drink. It’s something to do. Personally, I don’t like it that much. The rest of them can’t wait to get drunk. It’s too much out of control for me. I like a drink or two, but I don’t like getting stupid. The rest of them seem to want to get as stupid as they can as fast as they can.

The rule is that everyone has to bring something. Todd can buy liquor sometimes, depending on who’s working. We usually buy beer. They don’t seem to mind as much if you buy beer but get reluctant if you try to buy any hard liquor. That’s all right by me; I don’t mind beer. Everybody else tries to steal something from their parents’ supply, usually some bottle from the back of the cabinet. Archie—who everybody calls Ash for some reason none of us can remember—always brings the worst stuff: Baileys Irish Cream, Drambuie, Tia Maria, an unopened bottle of crème de menthe. The crème de menthe was too much for Todd. “No more back-of-the-cabinet crap,” he said. “I’m not handing out beers to everybody if this is what you’re going to bring. It’s not a fair swap. You have to drink the crème de menthe on your own, Ash. Drink the whole bottle and then go puke on yourself.”

That’s usually how it went when we were drinking. Sadly, even if we weren’t. Unless Jodi was with us.

Everybody dreads birthdays, don’t they? Especially their own. I can’t think of a more pointless exercise than celebrating an event you really had nothing to do with—no control, no decision, no accomplishment other than being pushed into something, arriving on a more or less random date and time. I’ve never liked my birthday, even when I was little.

Of course the first one I remember was a disaster. We had moved from Oklahoma nine days before my fourth birthday. I was born in Norman, Oklahoma, which might be the only place I can think of that’s worse than here. My brother remembers Oklahoma. He wishes he didn’t.

My father went to the university there and hung around working at one bank and then another until he met my mother, who was finishing school. She’s originally from Chicago, so they say that’s how they picked here—it’s the midpoint between Norman and Chicago, but it’s not really. Still, it’s what they say whenever the subject comes up, which it almost never does, but at least they have an explanation prepared anyway.

We didn’t know anyone when we moved here, but my mother had a birthday party for me anyway, inviting the kids in the neighborhood. Maybe ten showed up. My mother thought there would be a bigger turnout, and she wasn’t happy. I remember that. She had three long folding tables set up on the deck in back of the house, with plastic tablecloths that had pirates on them, balloons, colored napkins, and pointed cardboard hats. There wasn’t a theme, obviously, only a strange assemblage of party clichés. The kid sitting next to me, Matt Boeringer, peed his pants within the first ten minutes. And never said a word about it. I still can’t see him without immediately recalling the smell. At least he tried to keep his mess to himself.

After we had cake and ice cream, Kaitlyn Douglas threw up all over the pirates, which led to a yard full of shrieking, hysterical kids running around gagging, trying desperately to keep their own chocolate cake inside them. I would wish for someone, even Kaitlyn Douglas (who has long since moved away) to come and vomit at one of my parties now—at least it would be a welcome change from the bland, almost-grim rites they have become. I don’t help matters, I know, and I can’t really blame my parents, but I would prefer if the day passed unnoticed. My mother won’t hear of it. So we have the usual cake and ice cream after dinner and my father hands me the same practical gift he has given me since I turned twelve, which is an envelope with a receipt for the amount he’s deposited in my college fund.

I hate birthdays. I hate holidays. I hate the calendar, which is both a circle and straight line, a wheel and an arrow, grinding around and shooting forward at the same time, each spin, each anniversary, each day a reminder of my failures, my lost plans, unfulfilled objectives and wishes—the days aren’t taken off the calendar, subtracted one by one, but added, another small stone accumulated, another foot moved ahead, the arrow flying forward instead of falling back to earth, when all I want is a complete stop.

The only good thing that happened at that first birthday in town, or at any birthday for that matter, is that I met Jodi. She wasn’t from the neighborhood, but, according to Jodi’s mom, my mother saw them at the store when she was stocking up on party stuff and invited her. I don’t remember her being there that day—nothing remarkable happened, nothing memorable—but we both remember the disaster it was. In fact, the event would have probably passed into the dim shadows of lost history if we hadn’t met again on the first day of preschool.

She started crying the second her mother left her in the morning, and for some reason, Mrs. Bradley brought her to me. I was playing with something—Jodi remembers it as a plastic pony, while I like to think of it as a plastic pistol—and whatever it was, or whatever I was doing, seemed to calm her or distract her and she stopped crying. We’ve been friends ever since. If somebody put a knife to my heart (and they have), I would probably say that Todd is my best friend, but it’s really Jodi. She’s known me the longest, knows more about me than anyone else, and doesn’t care about the bad stuff. I like it when she hangs out with us, but she usually only comes if she can convince some of her girlfriends to come along. It’s not an easy convincing.

As I mentioned, there are two bridges in town, and they’re within a few hundred feet of each other. The older bridge is all iron, built almost a hundred years ago or something like that, and hasn’t been in use for over five years. It stands there like a carcass picked clean, its bones hung out for everyone to look at and be reminded how inadequate it was. The new bridge is solid, heavy, a massive, soaring, slightly curved concrete that doesn’t at all appear to rise out of the water but forcefully sits in it, planted, as if steadying itself for a fight. The old bridge, on the other hand, is airy, frail; the iron gridwork seems too delicate to hold a single car, let alone the hundreds, thousands, the millions that crossed over it. Now it is left, discarded, like the steamboat that sits downriver. It isn’t even worth tearing down, I guess, so it has to wait there, forgotten and lonesome, with its middle hanging out open, until it rusts and decays and time and the river can take it. It was fine for decades and decades, and now it’s not even good enough for scrap.

It was too low, for starters. The middle section had to swing open to allow barges and larger boats through. This meant that traffic had to be stopped while the center detached and swung parallel to the river, the boats and barges allowed to pass, and then the section swung back in place and the barricades lifted and the anxious drivers started their cars and continued. No one wanted to get stuck on the bridge when it opened—it was a long process, maybe twenty minutes at its fastest, sometimes lasting as long as an hour and a half, depending on the length of the barges, the number of them, and how well they coordinated with the bridge operator, who sat in his box of an office, barely bigger than a phone booth, watching the river and waiting to drop the wooden gates and trap the traffic trying to get across the river. I always thought it would have been a great job, being the man in that box, but no one sits there now.

I loved watching the middle section of the bridge swing open, as easily as a gate, seeming to weigh no more than your arm, bending at the elbow until it stopped perpendicular to your bicep. Few people seemed to enjoy it as much as me; it was a nuisance that had to be endured, and best to be avoided. The problem was, nobody knew when the bridge was going to open. There was no schedule or even much warning. The red lights would come on and the gates would close and that would be it—you were going to be on the wrong side of the bridge for a half hour or more. People would get out of their cars and lean against the railing, smoke cigarettes, talk to their neighbors, throw coins or trash into the river below.

It was nighttime when we were on the bridge, my older brother, Michael, in the passenger seat and my mother driving. My father was out of town somewhere, so Mom had taken us across the river for dinner. We were coming back when the traffic stopped. Everything seemed to stop. My mother and brother were as still and quiet in the front seat as cardboard cutouts. A string of red taillights stretched ahead of us by fifteen or sixteen cars. Cars passed us going the opposite way, but they ran out as the rest of them were left waiting on the other side of the wide gap up ahead. We sat there in silence for at least fifteen minutes until I heard a sound, nothing more than a noise at the edge of my hearing. At first I wasn’t sure if it was coming from outside the car or inside, and then I realized that it was coming from inside me, a sound I’d never heard before, a low murmur, maybe a voice. It wasn’t in my ears but seemed to be coming from inside my bones. As it grew louder, I realized that it wasn’t a voice—I’m not even sure if it was a specific sound; it seemed more like a tone, an enveloping note that filled me, that almost shook me as it emanated inside me, a strange, meaningful roar, like the roar of a crowd at a baseball game, urging a player on, a thousand individual voices making one unified sound, but it wasn’t that; it was unlike anything I’d ever heard before, but I seemed to recognize it and knew instantly what it meant. I felt like a tuning fork, vibrating after it’s been struck. I rolled down the window to see if that would help, to see if that would let some of the sound out of me, but it didn’t change anything. It was an urging, a calling, a beckoning, an invitation and plea.