Janae #2

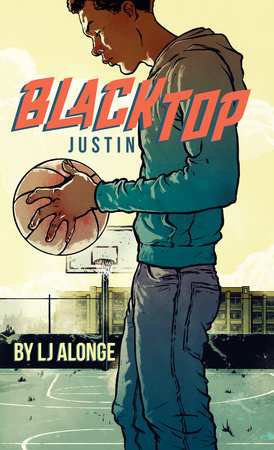

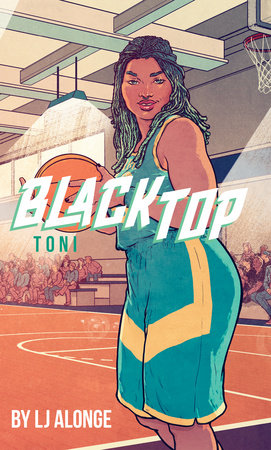

Part of: Blacktop

Paperback

$7.99

More Formats:

An action-packed basketball series from author LJ Alonge set on the courts of Oakland, CA.

Janae works every day at her Granny’s Strange Goods Superstore, selling lucky rabbits’ feet and other useless junk. And every night, after closing up shop, she dominates the courts with her boys.

When the chance comes around to take her game to the next level, she knows she’ll make the cut. It’s all about skill—luck’s got nothing to do with it. Right?

Janae works every day at her Granny’s Strange Goods Superstore, selling lucky rabbits’ feet and other useless junk. And every night, after closing up shop, she dominates the courts with her boys.

When the chance comes around to take her game to the next level, she knows she’ll make the cut. It’s all about skill—luck’s got nothing to do with it. Right?

- Pages: 144 Pages

- Series: Blacktop

- Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

- Imprint: Grosset & Dunlap

- ISBN: 9781101995648

An Excerpt From

Janae #2

Basketball chooses you. It’s just one of life’s mysteries—like the existence of yawning or gravity—a thing no middle-school science teacher has been able to explain for ten thousand years. But everybody who hoops remembers the exact moment they were chosen. It gets tattooed in capital letters somewhere deep in the animal part of your memory, the same part of your brain that remembers your first crush. You show up to the park on a summer morning planning to put up a few jumpers, just for fun. Maybe practice a little crossover or reverse layup you saw on TV the night before. You make a bunch of shots, you miss a bunch—everything’s good. Except: It’s early, and you’ve got time, so why not put up a few more jumpers? And you do that. And you feel good enough to put up a few more, and a few more after that. And then, without even realizing it, you’ve left the planet. You’re somewhere else.

In this new world, it doesn’t matter that your arms and legs are deadweight, or that the back of your neck’s been on fire for hours, or that your mouth is Sahara-dry, or that your stomach’s rattling around in your abdomen like a pebble in a shoe. Doesn’t matter that your ball’s flat, the court’s cracked, the rim’s crooked. Doesn’t matter that you were supposed to be home three hours ago. Doesn’t matter how many you’ve made, how many you’ve missed. You’ve left Earth, and on your new planet, living means putting the ball through the hoop. A few more times. And a few more times after that.

When you do finally get home, you wash up, you eat, you do chores, you lie down. It should feel normal, but it doesn’t. Your granny asks what’s wrong, but what can you say? You’ve got a roof and a bed and a full stomach—you should be happy. All you know is that something’s off. Home doesn’t feel like home; it just feels like a place to rest, somewhere to wait around, a bus stop. Usually you can fall right to sleep, but on this night, you can’t. Since there’s nothing like a sleepless night for some philosophizing, it hits you that “home” is just where you feel most comfortable, the place that makes you feel the most like yourself. The place that makes you feel the most free. That place, you suddenly realize, is the blacktop. Out there on the blacktop, with the sun beating down on you, and your shot clanking off the rim, and your feet throbbing, you felt free for the first time in your life. Really truly free.

That’s how you know you’ve been chosen. And when you’re chosen, there’s no turning back. From then on, forever, the game has you.

* * *

Granny likes the Strange Goods Superstore to open at sunrise. Of course that doesn’t mean she’s the one doing the opening. Earlier, as the sky went from black to foamy gray, she turned up the TV to ear-splitting volume and shuffled loudly into the bathroom. I was already awake, listening to her run the bathwater, hoping she wouldn’t call out to me.

“Get up, Janae!” she yelled, her voice made deep and monstrous by the steam. “You ain’t here on vacation.”

She hates it when I sleep late, and so I lay there, quiet and defiant. A few minutes later I could feel the air mattress shake as she marched down the hall. When she threw open my door, I only saw her outline. Her squat body filled the doorway like an eclipse, blocking out the light from the hall. I pretended to be asleep, watching her with my eyes barely open.

“You swear you’re the slickest kid in this whole world,” she said, flicking on the lights.

Now I’m sitting behind the register downstairs, trapped in that annoying spot between wakefulness and sleep. Right about now I’d kill for the thin, scratchy sheets on the guest bed, the same sheets my mom used when she was a kid. I put my head on the counter, and the glass holding our Weird Souvenirs collection cools my cheek. The lights are dim (we tell people it’s for the protection of our most delicate items), and suddenly I feel my eyelids getting heavy. I won’t fight it. No one’s coming in any time soon. Between lazy blinks I can make out the idling garbage trucks and taxis on the street, big clouds of exhaust chugging out of their tailpipes. It’ll be a few hours before the other stores roll up their steel gates and begin selling their conventional wares, their buttoned-up customers passing by our windows with curious glances. Our customers, like our hours, are strange.

The bells on our front door wake me up. I don’t know how long I’ve been out. A cold burst of air knifes in, and behind it is Ms. Evans. She unwraps the thick scarf covering her nose and mouth. She’s scowling, the deep wrinkles in her face crumpled into an angry mask.

“This doesn’t work,” she moans.

She slams down a multicolored wooden ring, and it spins on the glass counter like a top. Purple swirls of ancient-looking text run down both sides. On top is a cracked green jewel. Small splinters of wood splay out from the band. It’s from our igneous rock line.

“Sure it does,” I say, yawning for effect.

She folds her arms. “Then how come I don’t feel any better?”

“Our policy, Ms. Evans.” I point to the eye-level sign written in all caps behind me: no refunds.

Ms. Evans is our most loyal customer. She’s here every day, rubbing our lucky rabbits’ feet on the nape of her neck, weighing the steel pieces of our antique Ouija boards, flipping through our dusty treasure maps. It didn’t take much work to sell her the scarf she’s currently wearing. We tell people it’s made from Himalayan cotton, grown in the thinnest air humans can breathe and spun by the expert hands of lady Sherpas. I’d rubbed it on her cheek and told her the scarves improved circulation, feeling guilty as I watched her eyes light up with wonder. She bought five of them, and I helped her wrap the other four for her grandkids. Lying to her makes me feel crappy, and that, I’m now realizing, makes me angry.

I sigh. “Try putting it on a different finger.”

She holds out her brown, liver-spotted hands and wiggles her fingers. “Which one?”

“Any. Doesn’t matter.”

“Well, if this one isn’t working . . .” She pauses. Her fingers flutter above the glass. Below the glass sit orderly rows of gold-colored rings and bracelets; the little signs attached to them say they dramatically improve mood, joint health, and sexual stamina. Granny expects these to sell fast. “Maybe I should just get another one?”

I want to grab her by the shoulders and shake her. Ms. Evans, who told you to believe in this crap? I wonder. You won Science Teacher of the Year three times. You have a daughter who’s a doctor and a son who’s a detective. You once showed me how the inside of a watch works.

She’s bent over, staring through the glass, her lips parted as she reads the signs. I can see her pulse through the thin, waxy skin on her neck. Her wig is slightly crooked under her hat.

“Well,” she says, “I do need more stamina.”

“Here,” I groan, grabbing the tray of rings, “let’s look at a few things from our new collection.”

* * *

I wait until Ms. Evans leaves to slam the register. I hate it here. I hate the wobbly, three-legged stool behind the register. I hate the stinky fly traps we keep near the bathroom, the off-key bells on the front door. Outside, with the fog rolling away, everything looks soft-edged and warm. If life were fair, I’d be out there playing twenty-one until my hands got calloused. I’d be talking shit to the boys who never put me on their team. I’d snarl at the girls who glare at me, as if I wanted their knock-kneed boyfriends. But Granny’s grooming me to be the next manager, and that means I work long hours cheating people out of their money.

The Strange Goods Superstore was opened by Granny twenty years ago. According to our sign, we’re “proud purveyors of the peculiar.” Walk down one aisle and you’ll find volcanic stones that boost energy. In the next you’ll find a pile of water diviners stacked together in a thorny mess. Our Egyptian salts, supposedly aged for hundreds of years in the tombs of pharaohs, are locally famous. When used in your bath, they’re supposed to make you appear younger. And if you bring in any of Granny’s numerous profiles from the local paper, you get a 10 percent discount.

Every summer my sisters and I are shipped up here to restock the dream catchers and healing cloths, the prosperity purses and books on elementary divination. I used to love it. Granny would sit at the register humming upbeat jazz songs. Vanilla incense wafted out of the front doors. Old dreadlocked guys would sit on the sidewalk just outside, smoking weed out of handmade pipes and eating sugar-free cookies. Granny would have to drag me by my collar to bed.

But one unusually warm night last summer I went to the kitchen for some juice, and there she was, boiling down a big pot of Morton table salt.

“What?” she asked, turning up the heat. “Santa ain’t real, either.”

Granny says she wouldn’t trust my sisters to spot the stripes on a zebra. That means I’m the sweet-faced front for the whole operation, the one she plans to leave all of this to. Now I do all the restocking, returns, opening, closing, and bookkeeping. It’s joyless, guilt-inducing work. A dozen Ms. Evanses come in every day, looking for answers to failing marriages and arteries, out-of-control colons and kids.

Now that I do all the work, Granny stays in our apartment upstairs. Lately I’ve been starting to worry about her. She paces around the living room all night, chain-smoking and binge-watching Unsolved Crimes. Whenever they find the perp, she shakes her head and looks through the blinds suspiciously.

“Don’t you want to go somewhere?” I asked once.

Ghostly light from the TV washed across her face. “With what money?”

“I thought you had money, Granny.”

Her laugh is bitter and phlegmy. I suddenly remember the gallon of quarters and half dollars in the back of her closet—my college fund.

“Okay,” I say, “let’s say the store made a bunch of money.”

“Unlikely!”

“Let’s say I make it playing basketball. We could go anywhere you want.”

“Ha!”

“What’s so funny about that?”

“A boy’s game?” Granny asked. “You want to make a life playing a boy’s game? This right here, this is life.”