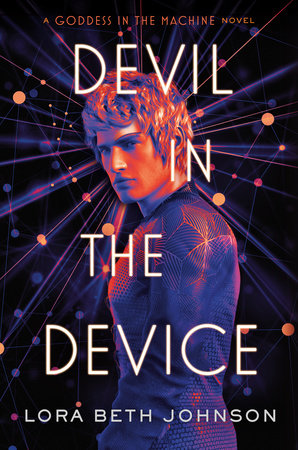

Goddess in the Machine

Paperback

$11.99

- Pages: 416 Pages

- Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

- Imprint: Razorbill

- ISBN: 9781984835949

An Excerpt From

Goddess in the Machine

When Andromeda woke, she was drowning.

They’d warned her this would happen—that her lungs would burn and her eyes would sting and she’d have to fight for that first breath. But you must take it, they said. If you don’t, your lungs will collapse and we’ll have to put you in a coma and just hope for the best.

Okay, maybe those weren’t their exact words.

She pulled in a breath, just like they told her. It burned. It stung. She fought. Water flooded her lungs, and the bitter taste of saline filled her mouth. Something was wrong. Something she couldn’t quite place.

Her fist shot out, grasping for help, but it slammed into something solid. There it was—the wrongness. Ten-inch-thick metallic glass enforced with veins of diamond dust. Latched together with hinges of a tantalum-tungsten alloy. Supposed to be yawning open when she woke. But it wasn’t. It was still closed, cocooning her in cold metal and melting cryo’protectant.

Calculations fired in her brain, searching for missing information, evaluating variables, solving for X. She’d just been put to sleep, and now she was drowning. No. It only felt like she’d just been put to sleep. It had actually been a hundred years. And now, she was waking up and (oh god) naked, but her chamber was still closed.

Something was definitely wrong.

They’d prepared her for this possibility—waking too early or crisis aborts or faulty latches—but it was hard to remember emergency plans in the middle of an emergency.

There was a button somewhere . . .

. . . or a switch?

She was too lightheaded. Her hands didn’t work. Her brain was shutting down, synapses sparking, sending a single message:

air air air air air

She struck the glass again. It didn’t even crack. It was meant to last centuries, meant to withstand zero gravity and a thousand times atmospheric pressure and two thousand degrees kelvin and zero degrees kelvin. But she kept pounding, each hit a bit weaker, a bit quieter.

She hit the glass until her strength gave out. Her arms fell to her sides. Just before her eyes slid shut, she saw a face above her. No one she recognized. There was no bright light. No life flashing before her eyes. No air. Just water and drowning and dying and water.

Then nothing.

When she woke the second time, she was coughing up saline. This was an improvement.

Her throat was sore. It ached down into the recesses of her chest. She didn’t want to breathe. It hurt too much. But she had to.

Just as soon as she coughed all the water out of her lungs.

At first, her senses didn’t extend past pain. Then she heard shouts. Murmurs. Whispers. Syllables that weren’t words. Words without meaning. Strong arms held her, a rough hand patted her back. Not the cryo’tech—they weren’t allowed to touch. Not her mom either—she didn’t coddle.

The water was gone now, but the sting remained, the compulsion to cough. She gasped in a breath, and it dragged through her lungs, her throat, catching and tearing as it went. But it kept her alive, so she pulled in another.

And another.

Shivering. Shaking off flecks of ice.

So. Cold.

She thought about opening her eyes, but decided against it. Too much work. So she breathed, and then she slept, and then, for the first time in a hundred years, she dreamed.

Will I dream? she asked.

No, you’ll be sleeping too deeply. Like a computer shutting down.

Will I know time is passing?

When they wake you, it’ll feel like seconds from now.

When will they wake me?

When you reach the new planet.

So. You’re the last person I’ll ever speak to on Earth.

Don’t be so morbid.

The third time, Andra woke to the tinny whirring of a fan. A blast of air hit her right cheek and shoulder, alleviating some of the oppressive heat. Sticky globs of residual cryo’protectant clung to her skin. She shivered and opened her eyes.

She was awake. She jerked into a half-sitting position. This was a new planet. A hundred years had passed. She had to find her family. She had to tell her mom she was sorry. She—

was in the dirtiest room known to man.

The floors were dirt, the walls crusted with something she hoped was dirt. It was like a cave, a single shaft of light filtering in through a high, thin window with no glass or holo’screen, and a plume of sand puffed in on an arid gust of wind.

The room was empty except for the bed she was sitting on, a metal table, and, on top of that, the fan—which looked like it was running on some sort of kinetic energy. It spluttered to a stop, leaving the room silent and stale.

This was no place for medical tests and routines, for purgative baths and reanimation therapy. Andra hadn’t bothered to read the manual, but her mother had droned on about it enough that she knew the reanimation procedures by heart: once they arrived on the new planet, robots would wake the head LAC scientists—like Andra’s mother—and a skeleton crew of cryo’techs. They wouldn’t wake the colonists until mech’bots had constructed the hospitals, until everything was organized and sanitary. Then, after resurrection, there would be sight tests, vocal tests, muscle tests, preliminary physical therapy, a nice hot bath, and finally: reconnecting with family.

The point was, all of this was supposed to occur in a pristine, sterile environment.

The harsh mattress beneath her groaned. The quilt covering it was gritty under her fingers, caked with sand. Without the fan, the heat was unbearable, and she was dripping in sweat and cryo’protectant.

But no longer naked, so there was that.

Her clothes: unfamiliar and uncomfortably hot—loose pants, cuffed at the ankle, and a rough tunic with a cowl-neck rucked around her shoulders. Everything was a little too tight, like the clothes her mom would buy to inspire her to lose weight. Her forearms were covered with a constricting, stretchy material, and her wrists itched where sweat had gathered under the sleeves. The fabric was handmade; she could tell by the rough weave. These were no LAC-sanctioned medical robes, that was for sure.

On instinct, she mentally reached for her neural’implant, hoping she could use it to switch on an enviro’con, but found nothing. That was to be expected, since ’implants were known to glitch after stasis. She wouldn’t be able to access any technology around her for an indeterminant amount of time. Andra hated that word—indeterminant. She liked for things to be determined.

She brushed her short, dark hair out of her face. Her fingers caught in the tangles just as the door swung open, and another gust of wind blew in, along with a man, who stood silhouetted in the doorway. A cryo’technician. Finally.

Andra tried to blink away the fuzziness. Right before the cryo’tech had put her to sleep, he’d told her to state her name, age, hometown, and CID as soon as she woke up. Andromeda Yue Watts. Seventeen. Riverside, Ohio. 32-638-27. That’s what she was supposed to say, but all that came out was, “Huh?”

Because he didn’t look like a ’tech at all.

He was young—probably only a bit older than Andra, maybe nineteen, twenty—but he looked . . . rough, haggard, raw. Blond. Crinkled eyes. His angular jaw was brushed with scruff, and his sand-colored tunic was deliberately disheveled. He leaned against the doorjamb, arms crossed, eyebrows lifted in a question.

And he was wearing leather armor.

Definitely not a cryo’tech.

“Show the toe, Goddess,” he said, and though Andra understood each word individually, she had no idea what they meant put together in that order.

He pushed against the wall and sauntered over to the metal chair, twirling it around to sit backward. He winked, and Andra realized belatedly that she was gaping at him. Not because he was handsome—though, he was—but because there was a boy in leather armor saying random words to her in a cave, and this was so not how she imagined waking up on a new planet.

“Evens, then?” he asked. “You slept forever. See?” He pointed to his chin. “I grew a beard while I waited. Makes me look charred, marah?” He tilted his head in a few different angles, so she could get the full effect. When she didn’t respond, he patted the bed. “Show the toe. We need to peace. Sun’s sinking quickish.” His voice was richly reedy, and he spoke in an accent Andra had never heard before. It was hard to pick apart the string of phonemes into words. Even once she did, they didn’t sound quite right. Mushy and rushed.

“I . . .” She trailed off, taking in her surroundings again. Dirt, dirt, a bed, an empty cup, more dirt. No clues as to where she was. Holymyth, obviously. That was the plan: to wake up when they got to the new planet. She could feel the distance. Like when she’d fallen asleep on the vac’train to visit her grandmother in the Maylarche and when she woke up, something in her body registered how far she was from home. That feeling—shaking, gnawing, unsettling—was a thousand, a million times more potent now.

She’d fallen asleep in one place and woken up across the universe.

No big deal. That was supposed to happen—waking up a gazillion miles away. But the rest of it—the dirty hut and the cryo’tech who wasn’t a cryo’tech . . .

“Where am I?” she asked, her voice raw. “What’s going on?” Rasping vowels, sticky consonants.

“You’re at luck I speak High Goddess.” He thrummed his fingers against the back of the chair. They were coated in sand. “No one else in this wastehole would reck your speech.” He held out his hand. “I’m Zhade.” The way he said it was halfway between shade and jade. “Been looking for you for nearish four years. There’s a kiddun’s game called Rabbit Rabbit—where one kiddun hides and the others have to find them, and you would be massive at that game.”

Andra stared at his hand. It was wrapped with dirty bandages. He turned it over and looked at his palm.

“This is something you do, marah? The hand-shaking thing? Fraughted ridiculous custom.”

Andra swallowed, her brain struggling to keep up, as though it were slogging through knee-deep mud. “Four years? What do you mean you’ve been looking for me?” The room grew dark, a cloud passing over the sun. The air didn’t cool. “My family. I have to find my family. Is this Holymyth? Did something happen while we were in stasis? Where’s the cryo’tech?” Again, she reached for her ’implant, hoping to ping her family, but found nothing.

“That . . .” The soldier frowned. “. . . is a lot of words I don’t reck. I’ll get Wead to fetch you something to eat, but then we need to go road-wise.”

Andra swung over the side of the bed. Her legs ached, but not as badly as her throat. She wobbled as she got to her feet, but didn’t fall. Minimal muscular atrophy, her mother would have said—was probably saying right now as she woke someone else up from stasis.

Maybe Mom was waking up Acadia or Oz or Dad. Maybe she was looking for Andra right now. Or maybe . . .

She hobbled to the door, her muscles stretching in ways they hadn’t for a hundred years, even though in her mind, she’d used them just a few hours ago.

“Heya!” Zhade called. “Where are you peacing to?”

She pried open the door, expecting—

well, she didn’t know what she’d been expecting, but it certainly wasn’t this.

She stood at the top of a hill, in a village of rock huts. Not huts made of rocks, but huts carved into rocks. Enormous boulders, stories-high, with hollowed-out windows and doors and rooms. Dozens of structures sprouted from the ground. And beyond, as far as the eye could see: desert.

They were supposed to land somewhere subtropical. Somewhere lush, with moderate temperatures and low humidity, and enough trees to hide the horizon. Not a barren desert filled with boulders. The whole landscape was wrong.

But not as wrong as the people. Hundreds of them, all dressed like Andra—covered head-to-toe, despite the heat. As soon as they saw her, the crowd instantly quieted, and then, as one, they fell to their knees, murmuring a single word. Over and over. One Andra knew, but couldn’t begin to understand. She looked back, and Zhade was standing in the doorway, arms crossed, a crooked smile on his lips. He raised an eyebrow and said the word the people were chanting, once and vivid and burning, and somehow, she knew he was talking about her.

“Goddess,” he said.

Then, “How do you like your worshippers?”

Something was definitely wrong.