Cara Haycak

What was it like to go back and visit the island your mother lived on?

I went to the island in 1993, before I started writing Red Palms. Visiting the island was thrilling and shocking and strange…just a lot of things all at once…and I tried to put those feelings into the book.

I was very proud and relieved that I’d found the island at all. I almost didn’t get there because I got the name of the island wrong! I might have gone to a totally different place that had nothing to do with my family. But as I was negotiating my passage with a fisherman, in my rudimentary Spanish, he figured out where I really needed to go and took me there.

My first impression of the island gave me a deep feeling of sadness, of disappointment. The village looked so ramshackle, like it might all fall down in a strong wind. It was my first exposure to a subsistence way of life where everything is hard earned, and I immediately understood why my mother wasn’t happy living there and how difficult it must have been for her.

But I spent a few hours taking photographs and talking with the islanders who spoke Spanish, and my feelings about the island changed. I began to see it as a place that provided a different kind of pleasure and happiness, one based on simplicity and living close to nature, and that this was very important reason why people chose to stay there, as the father in the story does.

The best part about visiting the island is that everything I saw there gave me big ideas that shaped the story I wrote. Finding the church and graveyard on the hill. Seeing a hut made from driftwood and the boats beached under their palm thatch shelters. A boy shouting to me from his donkey. All of it went into the book.

If I hadn’t visited the island, I doubt there would even be a book. So I’m grateful to have been there. I think that’s how Benita winds up feeling about the place at the end of the story as well.

What other kinds of research did you do for RED PALMS?

I needed to know specific things about life in Ecuador at the time the book was set (1932), so I could bring more detail to the story I wanted to write. Did they have radio? Cars? Electricity? Trains? Indoor plumbing? What were the main crops grown there? What foods were common? How were they prepared? I liked reading traveler’s diaries from around that time, because they made things come to life. Ecuador, Portrait of a People, by Albert B. Franklin, published in 1943, is a good one.

To create Yanasa’s language I investigated the lexicons of tribal people of South America, and then made up my own to sound like what I had found. The character of the crone came from my experience producing a documentary film on the Kayapo Indians of Brazil, when I spent a week in a tribal village on the Amazon River. A two-week trip in the mountains of Peru helped me to understand the spiritual beliefs of an ancient people.

To learn about jaguars, their behaviors and how they are hunted, I read scientific journals, stories about man-eating cats, and also about the incredible work of Dr. Alan Rabinowitz who wrote, Jaguars: One Man’s Struggle to Establish the World’s First Jaguar Preserve.

I researched how coconut trees produce a crop, the water management systems of medieval monasteries, plants of the region, tribal marriage rituals. And when I knew that the crone in my story would lead Benita through a female rite of passage, my research led me to look at Native American ceremonies and also took me as far back as the Ice Age, when priestesses used clay figurines as tools of divination.

Sounds like a lot of work, I know, but ultimately this kind of investigation makes writing easier because you don’t have to rely solely on your imagination to tell a story. In doing research, you just need to figure out how real things play into the story you’re trying to tell.

What was it like writing about an experience so close to your family? Was it hard to separate fact from fiction?

My family’s experience served as a jumping off point for the book, but there is very little reality in the tale. It’s only there in bits and pieces.

For instance, my mother told me that my grandfather built a thatched house with dormers, but I didn’t know how he built the house. I had to make that up. Although she told me that natives of the island poisoned the fish in a seasonal stream, she mentioned nothing about a celebration afterward or that anyone from my family participated in an event like this. But I imagined that the girl I was writing about would want to be there. And I knew my mother grew very disappointed with her father over the course of her time on the island, but Benita expresses that by running away which is something my mother did not do.

So, in essence fact gave birth to fiction but I wasn’t encumbered with trying to recreate the lives of my family or to avoid it either, since I didn’t have many details to draw upon.

For me, the process of writing the book was more like that writing exercise where you’re given a first sentence as a starting place and you must build a story based on how that sentence sparks your imagination. But in the case of Red Palms, it was one heck of a first sentence, because my family’s experience was so unique.

This story is based on your mother’s experience. Did re-imagining it from Benita’s point of view change anything in your feelings about your mother?

I think there’s a saying that first-time novelists tend to write about themselves. Benita is much like me: her reactions, her decisions, how she handles her frustrations, and ultimately her determination came so much from me that it almost hurts to admit it. The character most resembling my mother is the crone, the figure of wisdom and strength and solitude and kindness, who gives all that she has and knows to the young woman, so that she may take on these powers and thrive. That describes my mother and the role she played in my life. Also, in the same way the crone is a part of Benita after their time together ends, my relationship to my mother is constant and unwavering, even though she is no longer alive.

Do you have an idea of what happens to Benita after the book ends?

One of the ideas presented in Red Palms is that the big bad unknown holds a wealth of surprises, and that the bigger your dreams, the further you will go. The idea is that you should put yourself out there, into foreign worlds, to find out what strengths are inside of you. I’d like readers to imagine what the future holds for Benita, because I hope that will inspire them to reach for greater things for themselves.

What advice would you give to young writers today?

Keep writing. Because writers write. Even though you’re tired, or have other schoolwork to do, or what you wrote yesterday is no good. Because the truth is, we teach ourselves how to write by doing it. The more you write, the better you get at it.

Keep your doubts away. Don’t be hypercritical of your writing or judge yourself while you are doing it. That is not your job. Your job is to explore and to reach and to thrill and to hope on the page.

Open your eyes, ears, nose…your brain. Because the world you live in has a story to tell. Maybe you’ll hear a song on the radio with lyrics that express a desire you didn’t know you had. Maybe one day you see a very strange plant in a garden, and it practically talks to you. Or maybe your parents tell you a story about something that happened when they were a kid, and what you learn about life in the past makes you see your life today totally differently. You just have to open yourself up to what is there and all around you.

Why do you choose to write for young adults?

Now I’m going to get all mystical on you. It choose me. Probably because the creature inside, the entity that animates Cara Haycak is still a teenager. Yes, I’ve grown older, wiser, more patient (but only a little). I’ve developed in all kinds of good ways, but ultimately I became who am I during those formative years (13-20), and that basic person is the one who is writing books. It’s a good fit for me.

What kinds of books do you like to read?

I like fiction with a strong and unique voice, with a narrator who is smarter than me, told with a poetry of language that practically breaks your heart.

What are your favorites?

The Poisonwood Bible, by Barbara Kingsolver. The English Patient, by Michael Ondaatje. Anything by Edith Wharton, what a brilliant mind!

Tell us about your next project.

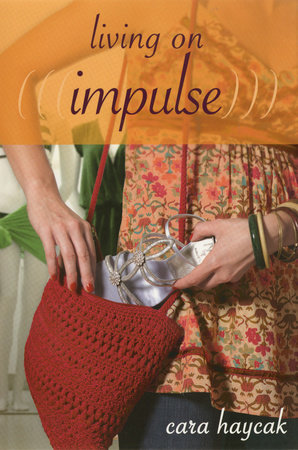

It’s called …mPulse (which is only a working title, don’t hold me to it!), and is about a girl named Mia, a high school junior growing up in a college town in upstate New York, who winds up taking a job breeding flies at the university in order to pay off a debt. It’s a story about metamorphosis: her’s, her family, her friends, the bugs she works with…everything in her life starts to shift and change very fast. It’s about recognizing and dealing with the natural cycles of life.

Your website (www.red-palms.com)looks great! What was it like putting that together and thinking of content?

Thanks! I had so much fun. I used to build websites professionally, so I had a site plan in mind from the start. I used the graphics designed by Marci Senders for the book jacket, which I love, and photographs I had of the island from my mother’s time and from my trip there. And then I worked with a talented web designer named Aaron Buckley here in LA, who brought motion and elegance to the pages. Ultimately I knew I wanted to bring readers closer to how the story got written…how I came up with certain things. It was really liberating to reveal some secrets behind the book, and to close that chapter of my family’s life. It was like putting the cap on the whole project, and once the site was done I knew I’d really let the story go…that it was going to live a life on its own.

I went to the island in 1993, before I started writing Red Palms. Visiting the island was thrilling and shocking and strange…just a lot of things all at once…and I tried to put those feelings into the book.

I was very proud and relieved that I’d found the island at all. I almost didn’t get there because I got the name of the island wrong! I might have gone to a totally different place that had nothing to do with my family. But as I was negotiating my passage with a fisherman, in my rudimentary Spanish, he figured out where I really needed to go and took me there.

My first impression of the island gave me a deep feeling of sadness, of disappointment. The village looked so ramshackle, like it might all fall down in a strong wind. It was my first exposure to a subsistence way of life where everything is hard earned, and I immediately understood why my mother wasn’t happy living there and how difficult it must have been for her.

But I spent a few hours taking photographs and talking with the islanders who spoke Spanish, and my feelings about the island changed. I began to see it as a place that provided a different kind of pleasure and happiness, one based on simplicity and living close to nature, and that this was very important reason why people chose to stay there, as the father in the story does.

The best part about visiting the island is that everything I saw there gave me big ideas that shaped the story I wrote. Finding the church and graveyard on the hill. Seeing a hut made from driftwood and the boats beached under their palm thatch shelters. A boy shouting to me from his donkey. All of it went into the book.

If I hadn’t visited the island, I doubt there would even be a book. So I’m grateful to have been there. I think that’s how Benita winds up feeling about the place at the end of the story as well.

What other kinds of research did you do for RED PALMS?

I needed to know specific things about life in Ecuador at the time the book was set (1932), so I could bring more detail to the story I wanted to write. Did they have radio? Cars? Electricity? Trains? Indoor plumbing? What were the main crops grown there? What foods were common? How were they prepared? I liked reading traveler’s diaries from around that time, because they made things come to life. Ecuador, Portrait of a People, by Albert B. Franklin, published in 1943, is a good one.

To create Yanasa’s language I investigated the lexicons of tribal people of South America, and then made up my own to sound like what I had found. The character of the crone came from my experience producing a documentary film on the Kayapo Indians of Brazil, when I spent a week in a tribal village on the Amazon River. A two-week trip in the mountains of Peru helped me to understand the spiritual beliefs of an ancient people.

To learn about jaguars, their behaviors and how they are hunted, I read scientific journals, stories about man-eating cats, and also about the incredible work of Dr. Alan Rabinowitz who wrote, Jaguars: One Man’s Struggle to Establish the World’s First Jaguar Preserve.

I researched how coconut trees produce a crop, the water management systems of medieval monasteries, plants of the region, tribal marriage rituals. And when I knew that the crone in my story would lead Benita through a female rite of passage, my research led me to look at Native American ceremonies and also took me as far back as the Ice Age, when priestesses used clay figurines as tools of divination.

Sounds like a lot of work, I know, but ultimately this kind of investigation makes writing easier because you don’t have to rely solely on your imagination to tell a story. In doing research, you just need to figure out how real things play into the story you’re trying to tell.

What was it like writing about an experience so close to your family? Was it hard to separate fact from fiction?

My family’s experience served as a jumping off point for the book, but there is very little reality in the tale. It’s only there in bits and pieces.

For instance, my mother told me that my grandfather built a thatched house with dormers, but I didn’t know how he built the house. I had to make that up. Although she told me that natives of the island poisoned the fish in a seasonal stream, she mentioned nothing about a celebration afterward or that anyone from my family participated in an event like this. But I imagined that the girl I was writing about would want to be there. And I knew my mother grew very disappointed with her father over the course of her time on the island, but Benita expresses that by running away which is something my mother did not do.

So, in essence fact gave birth to fiction but I wasn’t encumbered with trying to recreate the lives of my family or to avoid it either, since I didn’t have many details to draw upon.

For me, the process of writing the book was more like that writing exercise where you’re given a first sentence as a starting place and you must build a story based on how that sentence sparks your imagination. But in the case of Red Palms, it was one heck of a first sentence, because my family’s experience was so unique.

This story is based on your mother’s experience. Did re-imagining it from Benita’s point of view change anything in your feelings about your mother?

I think there’s a saying that first-time novelists tend to write about themselves. Benita is much like me: her reactions, her decisions, how she handles her frustrations, and ultimately her determination came so much from me that it almost hurts to admit it. The character most resembling my mother is the crone, the figure of wisdom and strength and solitude and kindness, who gives all that she has and knows to the young woman, so that she may take on these powers and thrive. That describes my mother and the role she played in my life. Also, in the same way the crone is a part of Benita after their time together ends, my relationship to my mother is constant and unwavering, even though she is no longer alive.

Do you have an idea of what happens to Benita after the book ends?

One of the ideas presented in Red Palms is that the big bad unknown holds a wealth of surprises, and that the bigger your dreams, the further you will go. The idea is that you should put yourself out there, into foreign worlds, to find out what strengths are inside of you. I’d like readers to imagine what the future holds for Benita, because I hope that will inspire them to reach for greater things for themselves.

What advice would you give to young writers today?

Keep writing. Because writers write. Even though you’re tired, or have other schoolwork to do, or what you wrote yesterday is no good. Because the truth is, we teach ourselves how to write by doing it. The more you write, the better you get at it.

Keep your doubts away. Don’t be hypercritical of your writing or judge yourself while you are doing it. That is not your job. Your job is to explore and to reach and to thrill and to hope on the page.

Open your eyes, ears, nose…your brain. Because the world you live in has a story to tell. Maybe you’ll hear a song on the radio with lyrics that express a desire you didn’t know you had. Maybe one day you see a very strange plant in a garden, and it practically talks to you. Or maybe your parents tell you a story about something that happened when they were a kid, and what you learn about life in the past makes you see your life today totally differently. You just have to open yourself up to what is there and all around you.

Why do you choose to write for young adults?

Now I’m going to get all mystical on you. It choose me. Probably because the creature inside, the entity that animates Cara Haycak is still a teenager. Yes, I’ve grown older, wiser, more patient (but only a little). I’ve developed in all kinds of good ways, but ultimately I became who am I during those formative years (13-20), and that basic person is the one who is writing books. It’s a good fit for me.

What kinds of books do you like to read?

I like fiction with a strong and unique voice, with a narrator who is smarter than me, told with a poetry of language that practically breaks your heart.

What are your favorites?

The Poisonwood Bible, by Barbara Kingsolver. The English Patient, by Michael Ondaatje. Anything by Edith Wharton, what a brilliant mind!

Tell us about your next project.

It’s called …mPulse (which is only a working title, don’t hold me to it!), and is about a girl named Mia, a high school junior growing up in a college town in upstate New York, who winds up taking a job breeding flies at the university in order to pay off a debt. It’s a story about metamorphosis: her’s, her family, her friends, the bugs she works with…everything in her life starts to shift and change very fast. It’s about recognizing and dealing with the natural cycles of life.

Your website (www.red-palms.com)looks great! What was it like putting that together and thinking of content?

Thanks! I had so much fun. I used to build websites professionally, so I had a site plan in mind from the start. I used the graphics designed by Marci Senders for the book jacket, which I love, and photographs I had of the island from my mother’s time and from my trip there. And then I worked with a talented web designer named Aaron Buckley here in LA, who brought motion and elegance to the pages. Ultimately I knew I wanted to bring readers closer to how the story got written…how I came up with certain things. It was really liberating to reveal some secrets behind the book, and to close that chapter of my family’s life. It was like putting the cap on the whole project, and once the site was done I knew I’d really let the story go…that it was going to live a life on its own.

Books by the Author