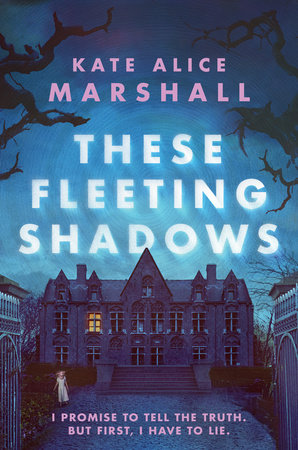

Kate Alice Marshall is queen of chills-up-your-spine creepy reads, and her newest novel is definitely no exception! Scroll down to read a sneak peek of These Fleeting Shadows, the perfect mix of The Haunting of Hill House and Knives Out about a bid for an inheritance that will leave Helen Vaughan either rich…or dead.

At that moment, the engine sputtered and died. Mom swore. She turned the key in the ignition but got nothing-not even a whine of the car attempting to start. She threw her door open and got out. Simon and I followed.

“What’s wrong with it?” I asked.

“Well, according to my extensive automotive knowledge, the problem is that the go part isn’t going,” Simon said, hands on his hips.

Mom pulled her phone out of her pocket. “Let me call Caleb. We can borrow a car, or . . . Damn it. I forgot-there’s never any signal out here. We’ll have to walk back to the house.”

“It’s not that far,” I said, trying to sound upbeat in the face of Mom’s distress.

She looked at me, face a wreck of worry. “I’ll go. You stay here,” she said. “I don’t want you going back there. Simon, you stay with her.”

I wasn’t really eager to go back to that strange house. But I definitely didn’t want her going alone. “I’ll be fine by myself. The gates are right there. I can always make a run for it,” I joked. Twenty feet to freedom.

Mom agreed reluctantly. “Stay put,” she ordered, giving me a quick hug before the two of them headed back. I watched as they made their way down the narrow lane, vanishing swiftly behind the trees as it bent.

The wind stirred the branches, making leaves shiver and branches rasp. I shifted from foot to foot, then started to pace back and forth. I almost didn’t see it-that slip of white among the trees. My gaze snagged on it as I turned, and I paused, trying to work out what it was.

A person.

The girl was about seven or eight years old, blond, wearing a simple white dress and no shoes. She crouched down just off the lane, her back to me. She seemed to be looking at something on the ground.

“Hey,” I called, frozen at the edge of the lane. She didn’t look up. Her shoulders moved, and I realized she wasn’t just looking at something-she was digging at the ground in front of her. “Hey, are you okay?” I called again and drew closer, uneasiness prickling at my skin.

The girl scraped up handfuls of dirt from the ground and shoved them aside, moving with frantic efficiency. I approached cautiously, a hard lump in my throat. The ground was stiff with frost, and yet she kept digging, her hands red and chapped, one nail torn and bleeding.

“Your hands!” I said, reaching for her. She turned, and I balked.

She had no face-none that I could see. There was only the crazed distortion of an ocular migraine, like a jagged crack in glass shot through with strobing light.

“We’re not safe here,” she said. Her voice was distorted, too, like I was hearing it underwater. “Please. You have to find me.” She sprang to her feet and dashed away along a deer track that shot through the trees.

“Wait!” I called, and without thinking or hesitating, I plunged after her. The path snaked ahead of me. A flicker of white flashed around a bend in the narrow trail, out of sight. “Stop!”

“Find me,” the girl said-and her voice was a whisper, but it echoed through the trees. I ran after her. “Hurry.”

I spilled out onto a wider path, this one lined with gravel that crunched under my heels. White bell-shaped flowers were scattered here and there. I caught glimpses of the girl flickering away at each bend in the path, but no matter how much speed I put on, she kept darting out of sight.

I came around a bend and halted abruptly. I was standing at the edge of the cemetery. My grandfather’s grave was a rectangle of brown earth among the green.

A young woman stood with her back to me, beside a worn headstone that was covered with clumps of moss. She wore a long gray dress and had a leather satchel at her hip. Her hair fell in waves around her shoulders, dark as the shadows among the trees. With a small hooked knife, she scraped some of the moss into a little glass jar before tucking it into her bag.

She twisted, looking over her shoulder, and spotted me. She scowled. Her face was sharp, almost fox-like. Not a comfortable face to look at for long, even from this distance. My heart beat fast in my chest, but I couldn’t tell if it was fear or something altogether different.

I drew forward, step by faltering step, and stopped short of the gate. “Hi,” I said weakly.

She arched an eyebrow. “What do you want?” she asked.

“Sorry. I didn’t mean to-there was this girl,” I said. “Blond, maybe seven or eight? I think she might be lost, so I was following her, but . . .” Except I hadn’t really thought she’d been lost, had I? Why had I run after her? I couldn’t remember now, and that sent a cold shiver of dread down my spine.

“It’s not a good idea to follow strange things into the woods,” she replied.

“She’s a girl, not a thing,” I snapped.

The young woman gave me an appraising look. “She’s not lost. She’s not dangerous, but it’s still not a good idea to let her lead you around,” she said, as if this clarified things.

“She’s . . .” I took a deep breath and dropped my voice to a whisper. “Is she a ghost?”

She gave a sharp startling laugh, like a bark. “No. There are no ghosts at Harrow.”

I flushed. “Right. Ghosts aren’t real. Obviously.”

“That’s not what I said,” she replied with exaggerated patience, as if I were a small child or a dimwitted pug. There are no ghosts at Harrow. My mother had said that, too. The girl sighed. “Haven’t they told you anything?”

“I’m just-my name is Helen. I’m here because-I’m Leopold Vaughan’s granddaughter? And there was a funeral, and . . .” I wasn’t sure exactly what it was I was trying to explain.

“Yes. I know. You’re Helen Vaughan, Mistress of Harrow. Waltzing in and claiming what you think is yours, just like the rest of your family.”

I blinked. “I’m sorry, what? Who told you that? I didn’t-who are you?”

She peered at me. “They should have told you that, too,” she said with a frown.

“Well, they didn’t. And I’m not Mistress of Harrow. I’m not mistress of anything. I turned it down. I’m leaving,” I told her with more confidence than I felt.

She studied me, considering. “It’s got a hold on you already,” she murmured. “You’ve got that look. If you walk away now, maybe it lets you go. But I doubt it.” She seemed to come to some conclusion. She reached into her bag and pulled out a small leather pouch bound with twine. She held it out over the iron gate. “Here. Take this. It’s not much, but it might help.”

When I hesitated, she shook the pouch impatiently. I drew forward and stretched out my hand. She set the little pouch in it, and as she drew her hand away, her fingertips brushed mine. A shock went through me, quick and sharp, and I drew in a hiss of breath. It felt-

I wasn’t sure. It had been so quick I couldn’t tell if it had hurt.

“Don’t run. It won’t do any good,” she advised, then turned away, done with me.

“Wait,” I said. She looked back, annoyed. Repulsion, disgust, and instinctive anger I was used to, but annoyed was new. And I had no idea what I’d done to earn it. “Did I do something to offend you?”

“Not yet, but give it time,” she said. With that, she turned on her heel and strode away, head held high, dark hair flung out behind her on the wind.